McGruder roots: Families trace lineages back to a single enslaved man

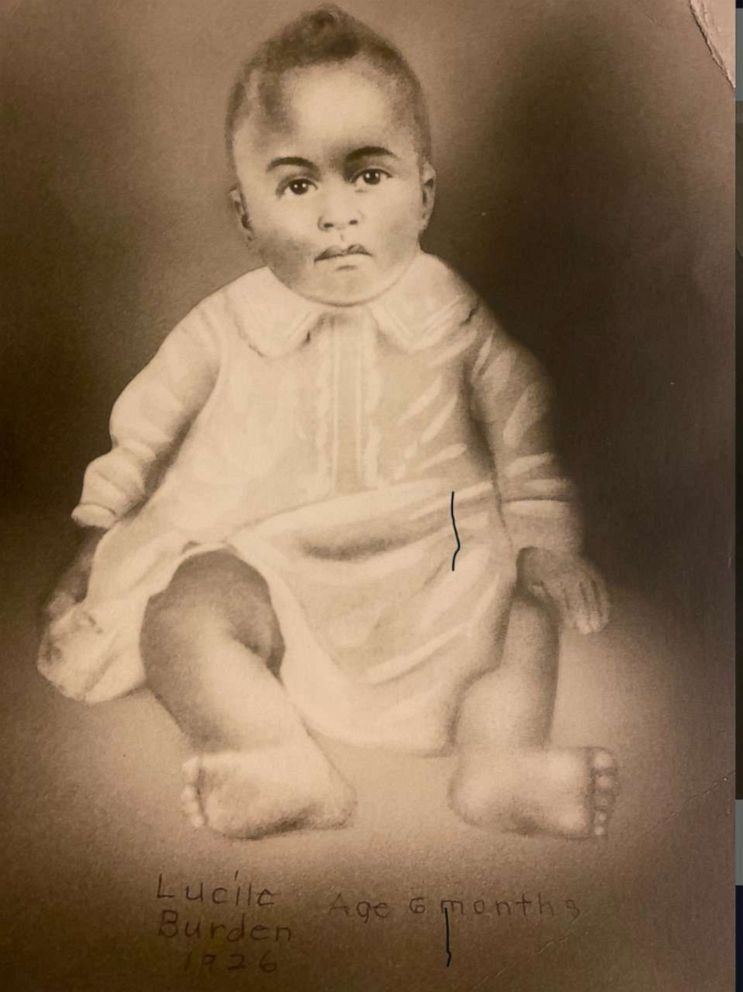

Lucille Burden Osborne, known by some as Miss Lucille, refuses to give cruelty the last word in her story.

At 95 years old, she grew up in the same house as family members who’d survived slavery, including her great-grandmother Rachel McGruder. Her great-grandfather, Charles McGruder, had also been enslaved.

As she grew up, Osborne had heard people speak about her great-grandfather, but people rarely spoke about the fact that he is the patriarch to most Black people from Alabama with the surname McGruder.

Watch “Soul of a Nation” TUESDAY at 10 p.m. ET on ABC. Episodes will be available on Hulu starting Wednesday.

“Evidently old man Charles McGruder must have been an important person to the community because we would hear his name many, many times,” said Osborne. “But nobody seemed to want to discuss how Charles fit into that slave situation, and it seemed like everybody would whisper when they were talking about Charles.”

She went on, “So this is what stands out in my mind -- that he must have been the big daddy … because during his early years, he was considered a [slave] breeder.”

Congress banned the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade in 1808. No longer able to import enslaved Africans, many owners forced people like Charles McGruder to procreate.

“Slave owners owned enslaved women's wombs, and they owned the products of enslaved women's wombs. And that was foundational to how white southerners understood and conceptualized slavery,” said Chris Bonner, a history professor at the University of Maryland. “Charles McGruder’s story reflects that sense of what slavery was.”

Marie McGruder, 58, told ABC News her great-great-grandfather “was basically rented out to go from plantation to plantation to breed with other African women.”

J.R. Rothstein said that his great-great-great grandfather may have had up to 100 children, but that the records confirm he had at least 40. Of those children, he said each of them had about a dozen of their own children, who then went on to have a dozen more.

He has since been dedicated to uncovering his family’s roots in a new book, called “The Alabama Black McGruders,” while he works as a real estate attorney and investor.

Bonner said that while the number of children Charles McGruder had is “shocking,” it doesn’t mean “that enslaved people didn't value family.”

After Charles McGurder was emancipated following the Civil War, he chose to make a homestead for the women and his children. It was an act of love for people connected to him through a vicious crime, because, ultimately, they were still his family.

After a decade of sharecropping, he purchased land in 1877 for $1,500 -- the exact same market value he commanded as an enslaved person. The family still owns part of that land today.

Jill Magruder is a descendant of the white Magruders who once owned Charles McGruder. Magruder is the original spelling of the McGruder last name. After emancipation, Charles McGruder registered to vote and changed the spelling of his family’s surname as an act of independence and to signal a new beginning, his family believes.

Most white relatives still carry the original spelling of the last name Magruder.

Through Family Tree DNA, Magruder said she was able to definitively link her branch of the family tree to Charles McGruder. The test showed an exact match between Magruder’s brother and Charles McGruder’s great-grandson, which confirmed that the two are indeed related.

ABC News connected Magruder with a small group of Black McGruders to talk about their shared family history.

“I know as a white Magruder, or just as a white American, you hear the stories about a slave owner having children with a slave woman, and there’s some kind of denial about that,” Jill Magruder said.

During the reunion, the McGruders passed around public records that confirmed Osborne’s memories of her great-grandfather, showing her for the first time the price placed on the lives of the people she knew and loved.

Osborne, a former Detroit school teacher, is a graduate of Alabama State University, an HBCU where she also joined the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, and the University of Michigan. An avid quilter, Osborne said she captures her story within the family tradition that she said was passed down through generations to her. She said her family’s legacy makes her proud to be who she is.

“They were once a slave and now they are free, so look at the legacy you got,” said Osborne. “If [they] made it through here, you can do even better.”