Manufacturing workers adjust to new protocols, face challenges in changes to demand

For Amanda Harbold, it’s been three long weeks at home. But now, she’s finally returned to her place of work on the factory floor.

“It was kind of emotional because of everything that's going on,” Harbold told “Nightline.”

Harbold’s job working the line at the Cummins Engine Plant in Seymour, Indiana, had been on pause as the company shut its doors amid the crush of COVID-19.

“I've lived in southern Indiana my whole life,” she said. “It's kind of my thing working on engines and I like hot rods and motorcycles, so that's kind of what brought me into it… I'm not someone who can just sit around the house. I was ready to come back.”

Last week, that facility reopened to a flood of eager employees and a slate of new safety protocols.

“We're asked a series of questions to make sure that we're not feeling ill,” Harbold said of the company’s new protocols. “Then we've got our temperature checked and we're given a mask for today. And then you're ready to go to work, build some engines.”

*Watch the full story on "Nightline" TONIGHT at 12:05 a.m. ET on ABC*

Creating everything from engines and oil tools to medications and even baseball bats, manufacturing is a giant of an industry, employing nearly 13 million people in the U.S. and powering how we move, how we work and how we live.

But as companies nationwide struggle to find their footing with more than 33 million people throughout the U.S. filing for unemployment in the last seven weeks, the manufacturing industry, which employs 13 million people, is feeling the pressure. Over one million people lost their jobs in the industry last month as it faces plummeting demand, supply shortages and factory closures.

Now, around the country, factories of all sizes and producing an array of products are fighting for a comeback.

In Colorado, Governor Jared Polis lifted the stay-at-home order at the end of the last month, allowing a slow re-opening.

There, brothers Barry and Kenny Carson realized that the key to saving their family business is doubling down on what they do best.

Xybix, a company that makes work stations for 911 command centers, has retooled the line in its 28,000 square foot facility in Littleton, Colorado, to begin pumping out plexiglass office dividers.

With many people figuring out how to safely get back to work in their offices, the company now produces devices that attach to a cubicle, creating a barrier to protect workers from airborne exposure spread by coughing or sneezing.The idea is the brainchild of customer service representative Karen Tinnes.

“I was at the grocery store and saw these plastic pieces that they had up and I was thinking, ‘Wow, we have this material at Xybix,’” Tinnes told “Nightline. “They took it and ran with it and implemented it within like a week.”

She says the company is now “inundated” with orders for the barriers.

“We’ve been talking to some of our suppliers to make sure they’ve got a good stream of material available,” Barry Carson, president of the company, said. “We’ve been pre-buying product we don’t even have sold yet because plexiglass is getting rare.”

For Kenny Carson, it’s more than just selling a product.

“A lot of the people we sell to and work for are the behind-the-scenes you don’t see: the radiologists, the 911 dispatcher who is the first responder,” he said. “We’re going to be there for them because they have to work. Especially right now, they don't have a choice. They have to go to work.”

In Indiana, where the state has cautiously entered phase two of reopening, the manufacturing industry employs almost 17% of the workforce. Cummins saw early on how the virus could impact its operations.

“It started for us back in January because we have a number of manufacturing facilities in Wuhan,” said Peter Anderson, vice president of the company’s global supply chain.

“Over 80% of our suppliers at some point closed down… We're still struggling with many of the suppliers, especially in countries that are still affected by this,” he added.

Cummins’ Seymour, Indiana, facility was closed for three weeks to implement new protocols, which reduced productivity but prioritized safety as the state battled with more than 24,000 cases of COVID-19 and 1,300 fatalities.

“I was nervous because I didn't know what kind of changes was gonna happen,” Harbold said. “But I feel, like, safe coming to work … with all the different changes, like the plexiglass in the bathrooms to make sure that when you're washing your hands, you keep your social distance and washing our hands frequently.”

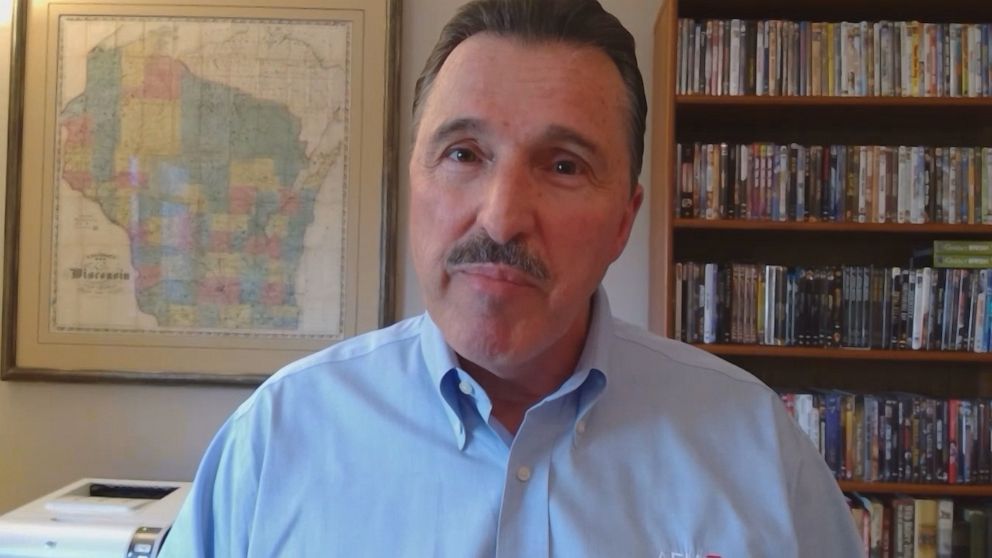

Dennis Slater is the president of the Association of Equipment Manufacturers. His group has put together a list of guidelines on how to keep factory production going safely in the age of COVID-19.

“This is nothing like the Great Recession where you had a reason for this bubble and you had to work your way out of it,” Slater said. “Today we’re working with a pandemic, which has now created an economic catastrophe, really, for our manufacturers.”

The high stakes are also palpable in nearby Bloomington, Indiana. It’s home to Catalent, a pharmaceutical manufacturer.

There, Nikki Rader leads a line assembling what she hopes may be the key in freeing the country from the clutches of COVID-19. Catalent is working with pharmaceutical companies to prepare COVID-19 vaccines through clinical trials.

“This is something that everybody has been affected by… It is a fear for everyone,” she told “Nightline.”

As the race to a vaccine gains steam, they are finding themselves in an enviable position — one of high demand.

Denis Johnson, the general manager of Catalent’s Bloomington plant, is now implementing lessons he learned from his years in the U.S. Army where he deployed troops for the Gulf War.

“You marshal your resources and you stop doing things you don’t need to do.” Johnson said. “So, essential right now is keeping our people safe, because without this team we wouldn’t be able to produce treatments.”

The hygiene requirements that come with the coronavirus are second nature for staff at Catalent, given the exacting demands of drug manufacturing.

“Everyone changes into clean rooms scrubs. Hair net, gloves, booties,” Rader said. “Anything to try and minimize any type of spread of bacteria.”

The work that has sustained these plant workers now offers a renewed sense of hope.

“Whenever we get up in the morning, we’re happy to come to work. But I think now, you have a little more pride whenever you come to work,” Rader said. “You know … you’re doing something big.”

Manufacturing had already been on the decline before COVID-19 hit American shores. Since 1980, 7.5 million jobs have been lost to automation and outsourcing. Now, the virus has caused the American economy to grind to a halt and accelerated job losses across the industry.

The oil industry has been hit particularly hard, as the price of oil was already in freefall due to a price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia earlier this year.

Kenny Istre is the vice president of Taylor Oilfield Manufacturing in Houston, Texas, and has been with the company for 29 years — almost since its beginning. The company specializes in building and repairing drilling tools.

“When the owner opened the company, we probably had about seven or eight employees ... and then from there we grew,” Istre said. “We leased a shop here in Houston for a few years, [a] little 4,500 square foot building. … Now I have 32,100 [square feet] under a roof here in Houston.”

For Istre, his employees are more than just people who work for him, making the decisions he’s had to make recently feel all the more cruel.

“A lot of my employees, I feel like they're family. And so having to lay people off every time, it's really hard to tell somebody that,” he said.

The oil industry, he says, has always been volatile. But never like this.

The recent price plunge has had a ripple effect across so many businesses that support the oil industry, particularly in Texas, where the state produces 40% of the country’s oil.

“It really affects everybody in the Houston area when this happens and the oil industry goes down… Now you have all these people not driving to work and all the planes not flying,” he said. “That much more fuel that's not being used and so now they have a stockpile of oil and that drove the price down even more.”

Istre believes that his company will survive this downturn as they had in the past.

“We're not planning on closing. We're going to battle through it and stick it out like we did all the other times and hopefully, hopefully we can make it through,” he said.

Once they do, Istre hopes he’ll have jobs waiting for the employees he had to let go.

“I told all of them, I said, ‘Whenever this is over and whenever we can, we're gonna hire you back,’” he said. “‘You know, it's just, you don't have to sit and wait. ... If you find something that's OK. But I will call you back when things pick up.’”