Manafort trial, first in Mueller investigation, gets underway

The financial crimes trial of Donald Trump’s former campaign chairman, Paul Manafort, got underway in Alexandria, Virginia, Tuesday, the first trial in connection with the more than year-long investigation by special counsel Robert Mueller into possible collusion between Russia and then-candidate Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign.

But collusion and Russia are not expected to come up during Manafort’s trial; rather, the white-collar crime case arose from the broader mandate given Mueller to probe matters arising directly out of the investigation into any campaign links to the Kremlin.

As part of that investigation, Mueller began exploring Manafort’s longtime work for Ukrainian politicians with ties to Moscow, which he began in 2006. Government investigators unearthed a raft of alleged financial crimes unrelated to the campaign and obtained multiple, related indictments against the veteran GOP lobbyist, including counts of tax evasion and bank fraud.

Manafort, who’s 69 and could spend the rest of his life in prison if convicted, has pleaded not guilty to all charges.

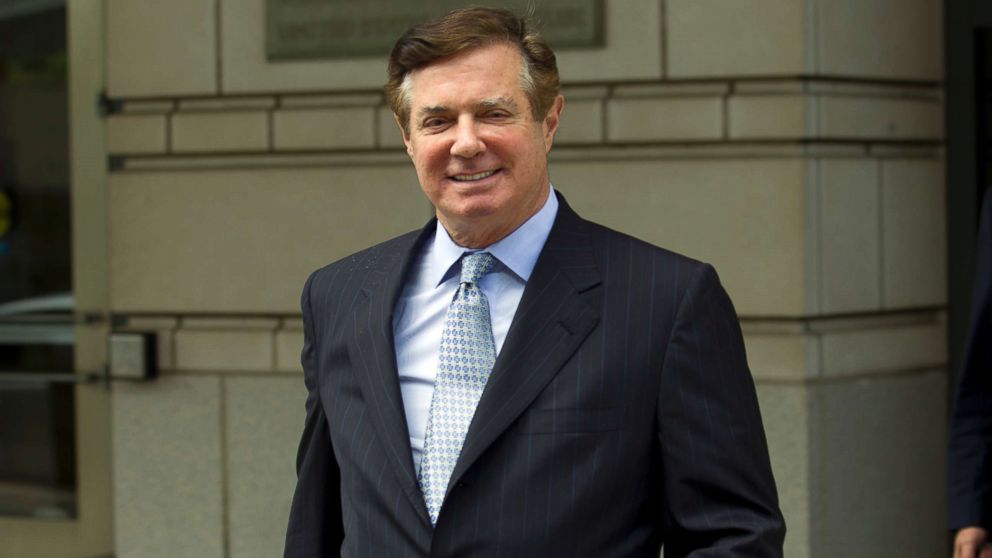

Federal prosecutors allege Manafort, who smiled as he entered the courtroom Tuesday morning, funneled some $75 million through offshore accounts, using a complex scheme to hide income, buy posh real estate, make home improvements to his many houses from the affluent Hamptons to tony West Palm Beach, and generally to live a life of luxury.

The exhibits list for the prosecution at times reads like a script from the set of “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous,” with photographs to be presented of pricey vehicles, opulent home furnishings and haute couture, including a watch from House of Bijan, which CNBC earlier this year labeled “the most expensive store in the world.”

In short, the prosecution is expected to attempt to paint Manafort as leading a criminal high-life to the jury of 12 men and women, along with four alternates, chosen from the Virginia suburb just outside the nation’s capital.

Former federal prosecutor Peter Zeidenberg, in an interview with ABC, called Manafort “particularly” unsympathetic “and completely unrelatable. He made a massive fortune working for a Russian stooge in the Ukraine. Hard to relate to that.”

But veteran white-collar defense attorney Shan Wu, said, “You make your client a sympathetic figure by showing him as a person – what they have done, what they have accomplished.

“In a high-profile case like this, I would emphasize the amount of resources the prosecution has expended against my client – that they have some other agenda in mind, because otherwise his crimes are not worth the amount of money, time and staff devoted to it. This makes the client a human being versus the government,” Wu said.

Making that last point might be hard for Manafort’s defense attorneys, Kevin Downing, Thomas Zehnle, and Richard Westling, who told federal judge T. S. Ellis last week that they do not intend to argue that their client was “selectively or vindictively prosecuted,” although the defense lawyers said they might raise the issue at a later date.

Manafort's overall defense strategy is unknown, largely due to a gag order on lawyers imposed by the judge in a separate case against Manafort in Washington, D.C. Manafort has maintained he had no contact with Russian President Vladimir Putin or other Russians.

One image the jury will not see is the defendant in his jail-issued dark green jumpsuit arriving from nearby Alexandria Detention Center, where he has been since June. He was sent there after the judge in his separate Washington, D.C., case ordered him held for alleged attempted witness-tampering. Instead, Manafort will appear in normal business attire.

Excluded at trial will be any mention of collusion and Russia, as decreed by the judge, but Manafort’s defense team was unsuccessful in efforts to exclude more than 50 government exhibits related to Manafort’s work in Ukraine. They had argued “strategy memos and PR don’t go to the financial crimes” their client allegedly committed.

Lead prosecutor Greg Andres took great exception, arguing that exhibits like photos of former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych on a Manafort-produced photo-shoot for his client were at the “core” of the government’s case.

“These exhibits...go directly to how Mr. Manafort made his money,” Andres said, adding, “The point is to show how he made not hundreds of thousands but millions and millions.”

Judge Ellis urged prosecutors to “be cautious,” noting that “most people don’t distinguish between Ukrainians and Russians,” but said he would allow the government to proceed.

Zeidenberg, a former deputy special counsel in the perjury and obstruction of justice prosecution of Lewis “Scooter” Libby -- former top adviser to Vice President Dick Cheney -- said the prime task of the prosecution will be to keep it simple.

He cited a daunting paper trail from countless emails and documents from cooperating witnesses to boxes and file cabinets of bank records and other items seized in a May 2017 raid on Manafort’s storage unit and another raid - on his Alexandria condo - two months later.

“The government always wants to simplify these types of cases as much as possible and illustrate the vast wealth that Manafort accumulated but never accounted for,” Zeidenberg said. “This should not be a difficult case to prove, particularly given the use of a cooperating witness like Gates,” a reference to former longtime Manafort business partner Rick Gates, who pleaded guilty to reduced charges earlier this year and has been cooperating with the Mueller investigation for five months.

Zeidenberg said jurors in the eastern district of Virginia “are generally pretty sophisticated,” adding, “This isn’t that tough. failure to report his foreign bank accounts and the bank fraud should not be difficult concepts for the jurors.”

Still, Wu said much depends on the skill of the prosecutors.

“So the way you defend a white-collar case with a lot of records arrayed against your client is to take on the narrative of those documents and make the story either sympathetic to your client or punch it full of holes,” said Wu, who at one point briefly represented Gates.

“Making complex evidence interesting and easy to understand is very much dependent on the courtroom skills of the lawyer. You have to know exactly how your evidence tells a story so you are presenting the story – not the evidence,” Wu said.

Perhaps the biggest day in court - and potentially the most damaging for Manafort - is when Gates, who also worked alongside his longtime colleague on the Trump campaign, takes the stand against him. The government’s exhibit list, alone, is littered with communications involving Gates.

The two were originally indicted in Washington, D.C., in October on conspiracy, false statements, and a slew of financial crimes related to their lobbying and political work on behalf of pro-Russia Ukrainian politicians.

Besides Gates, the list of 35 potential witnesses the government revealed Friday includes the former chief strategist to Sen. Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign, who worked with Manafort eight years ago to help get Kremlin-backed Viktor Yanukovych elected.

Former bankers, tax accountants, bookkeepers, a real estate agent, even the CFO at the Alexandria Mercedes dealership where Manafort did business will possibly take the stand for the government.

Though none of the witnesses is a household name, a number are from high profile institutions, such as the director of ticket operations for the New York Yankees and AirBnB’s director of customer experience for North America -- all companies with which the government says Manafort did business.

Five individuals from financial institutions and bookkeeping firms have been granted limited “use” immunity to testify against their former client without fear of prosecution. They are free from legal jeopardy in this instance only – a one-time “use.”

It is unclear if Manafort will take the stand. Wu noted that the defense strategy of humanizing a client is “much harder to do if they do not testify, which most criminal defendants do not do as it exposes them to the dangers of cross-examination.”

One person who is not expected to show is Robert Mueller, according to the special counsel’s office.

A component of the expected three-week trial that’s sure to be unpredictable and anything but simple is the judge himself.

T.S. Ellis, at 78 years old, is slight, balding with bushy eyebrows, ever-irascible, unpredictable, and fond of stem-winding jaunts through history or down memory lane of his 30 years of experience on the bench.

Over the last five months, the Reagan appointee has shown himself to be sympathetic toward defendants, scholarly in his opinions, irritated by mandatory sentencing guidelines, a scourge of any unprepared lawyer, ready with verbal quips and tongue lashings, and a fan of fast-moving proceedings.

The Eastern District court – of which Ellis’ courtroom is a part - has a long reputation as the “rocket docket” – moving proceedings along without delay.

Prosecutors have been applying great pressure on Manafort for the past year to get him to cut some kind of deal, so much so that Judge Ellis even referred to it in one pre-trial hearing, saying the government was trying “to turn the screws” and really just wanted Manafort, “the vernacular is, to sing.”

And while President Trump is not expected to be a topic in the trial, politicos will certainly be watching for his reaction, either through tweets or at a political rally scheduled for Tuesday night, announced by his campaign just a little more than a week ago.

Manafort was brought onto the Trump campaign by one of the President’s closest friends and confidantes, California real estate mogul Tom Barrack, who also kept Gates on to help run the Inaugural Committee after Manafort departed the campaign early on. Barrack has been interviewed by the special counsel investigators.

Just two weeks ago, Trump - on Fox News’ Sean Hannity show - called Manafort “a really nice man” before comparing his former campaign manager to a mobster brought down by his tax returns, “You look at what’s going on with him, it’s like Al Capone.”

President Trump could always offer his former campaign manager a pardon.

Trump’s own lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, in June did not rule it out, though he was adamant that no pardons be issued until the investigation is complete.

"When it's over, hey, he's the President of the United States. He retains his pardon power. Nobody's taking that away from him," Giuliani said on CNN's "State of the Union.”

When asked last month if he was paying close attention to Manafort’s legal predicament, Trump said, “They went back 12 years to get things that he did 12 years ago? You know, Paul Manafort worked for me for a very short period of time. He worked for Ronald Reagan. He worked for Bob Dole … He worked for many other Republicans … I feel badly for some people because they’ve gone back 12 years to find things about somebody, and I don’t think it’s right.”