Activists share first steps you can take to become an ally

This report is part of "Turning Point," a groundbreaking month-long series by ABC News examining the racial reckoning sweeping the United States and exploring whether it can lead to lasting reconciliation.

In the week after George Floyd was killed in police custody, protests erupted in cities across the United States. The Tuesday after Floyd’s death, more than 20 million social media users posted a simple black square, many accompanied with #BlackoutTuesday, flooding platforms like Instagram.

The posts were meant to show solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. However, within hours there was intense criticism of the trend.

Many supporters and activists argued that the posts were interfering with the spread of productive information about how to safely organize, and drowning out voices that needed to be heard, overshadowing the conversation that really mattered: How to protect Black lives.

Many who may want to get involved feel reluctance to risk backlash and hesitate, thinking, “How am I supposed to learn what to say and when to say it? What if I mess up? Why get involved at all?”

The debate over the black square is in some ways a microcosm of a climate that appears to urge people to get involved and take action, but also expects them to know exactly when to speak up, what to say and when to step back to make space for others.

Alicia Garza, principal of the Black Futures Lab and co-creator of #BlackLivesMatter, is one of many activists and community leaders who say the answer isn’t that complicated.

“If you share the value that everyone should live with respect, and the idea that people are being left behind enrage[s] you and break[s] your heart -- the only way to fix it is to become part of the solution.”

Movements need allies

Allies are people who aren’t directly affected by a problem, but invest time and energy into the cause. That includes everything from looking critically at their own lives and subconscious biases, to learning and having conversations about the movement, to donating money and marching on the frontlines of a protest.

“True allies begin to think of themselves as more than allies,” Fatima Goss Graves, CEO of the National Women's Law Center, told ABC News. “They start to realize that their lives, their fate, their futures are actually bound up with others.”

Nevertheless, agreeing that fighting for equality is morally right only goes so far. Gross Graves says it's a "much harder line of work" to expand the movement by convincing people to join.

And people are being spurred to action. In July, the New York Times proclaimed Black Lives Matter may be the largest movement in U.S. history. Well-attended protests reached some of the U.S.’s smallest, most rural towns, like Norfolk, Nebraska, Alpine, Texas, Lodi, California, Hagerstown, Maryland, and Taylorville, Illinois.

That includes the most privileged among us, the activists who spoke to ABC News said -- those who are not a part of a community that’s suffering are still affected by their plight.

Allies make mistakes

“We don’t want to talk to people who believe exactly what we believe in,” activist and founder and president of Justice for Migrant Women, Mónica Ramírez said. “If we don’t talk to each other, then we don’t have the opportunity to grow. … I’ve certainly evolved; people teach me things all the time.”

Knowing when to speak up and when to step back changes with each situation. All of the activists ABC News spoke to said people joining the movement will get things wrong, and that it’s OK.

“Change requires courage. Organizing is full of failures. That’s how we learn and [how] we grow,” said Ai-Jen Poo, director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance. “If you’re not taking risks, you’re not in the arena. … That’s the kind of bravery this moment requires.”

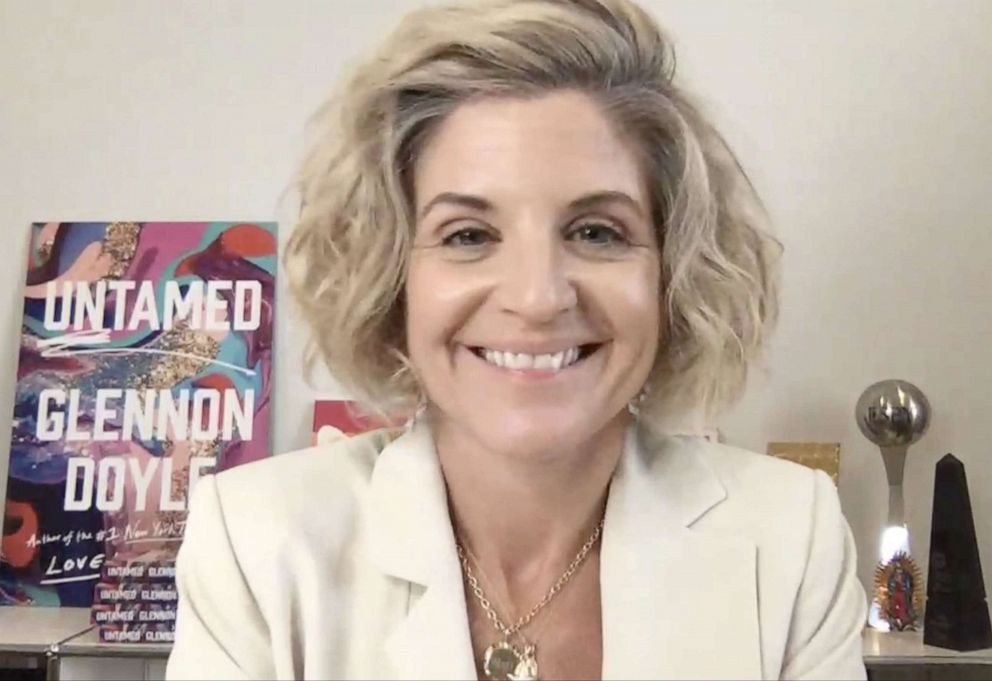

Despite urgings that making mistakes is okay, the reality is that an ally’s actions may be received with harsh feedback. Author and activist Glennon Doyle is intimately familiar with navigating that.

“It’s so intimidating to speak out in any way. There are people who believe that white women should never speak up in the race conversation… Absolutely valid,” said Doyle, who is a white woman. “Every time I speak up people from the other camp… tell me that.”

She said she decided it’s “a balancing act” of mostly amplifying other voices, but making sure, at the end of the day, that she put in the work herself and “left everything on the field. I’m going to need to be accountable for myself,” she said. “It’s ok if people don’t like me, it’s ok to be criticized. All of that is just part of activism.”

Being unaware of the right terms to use or actions to take doesn’t make someone unqualified to be an ally.

Ramirez says “any step in the direction of justice” is enough to start being an ally.

“I’m not one to judge people in the way they’re choosing to show their solidarity,” she said. “We have to meet them where they are; we should assume the best.”

However, she also said it’s each person’s individual responsibility to educate themselves on the issues.

Allie Young, who is Diné, meaning from the Navajo nation, says we can all get online and learn.

“It’s so simple nowadays to Google things,” she said. “There are so many resources that didn’t exist 10 years ago… Some of the responsibility falls on the individual, going out and self-educating. What we’re learning in school isn’t enough.”

Ramirez added that these issues can be too sensitive to bring up with friends who belong to these affected communities.

“It’s traumatic to have to relive and retell those experiences. That is an additional burden that we are placing on them. It’s really important … to be respectful and be sensitive,” Ramírez said. “We need to do the work ourselves, then ask for clarification.”

When should an ally speak up? When should they step back?

Young says her people are taught to live by hózhó, a Navajo philosophy that means“walking and living in balance.” For an ally, there is a time to listen and a time to speak up.

“If you are directly impacted by something, it’s always the right time to speak out,” Garza said. “If you are somebody who’s directly impacted by the way somebody else is being impacted, then that is a good time to assess, ‘Is it better for somebody else’s voice to be amplified?’ ... We have to make sure we’re removing the barriers for people to speak for themselves.”

Chivona Newsome, co-founder of Black Lives Matter of Greater New York, pointed out that allies should support a movement, not police it.

“It’s important for Black people to be at the forefront of leadership,” she said of Black Lives Matter, adding that it’s important for allies to respect their decisions.

“We need to stay silent when there are impacted community members speaking and leading… We need to follow their direction. What we should not do is try to become a spokesperson or try to become an educator on someone else’s experiences,” Ramírez said.

When it’s time to speak, she says it’ll be easy to tell -- “We will feel it in our hearts, feel it in our bodies.”

“There are times in which you see someone being beaten down verbally, or who’s being treated completely inappropriately and they seem all alone and defenseless. I think that is when we are compelled to speak and compelled to do something about it,” she added. “That is when we do not look away.”

Poo says it’s about “addition, not subtraction” to the ally cause.

“All of us are in the process of change and transformation… There needs to be room for that; room for debate, discussion and grappling,” she said. “There’s no such thing as an unlikely ally. We have to hold [onto] that... I don’t agree with everyone I organize with … but there’s a reason we come together.”