In Maine, casting ballots with, and on, ranked-choice voting

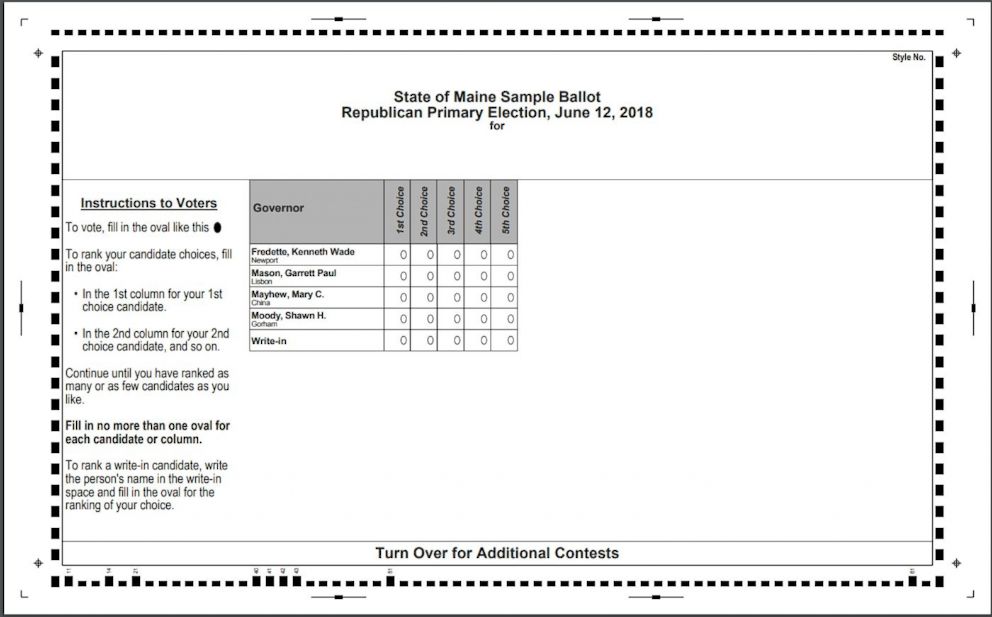

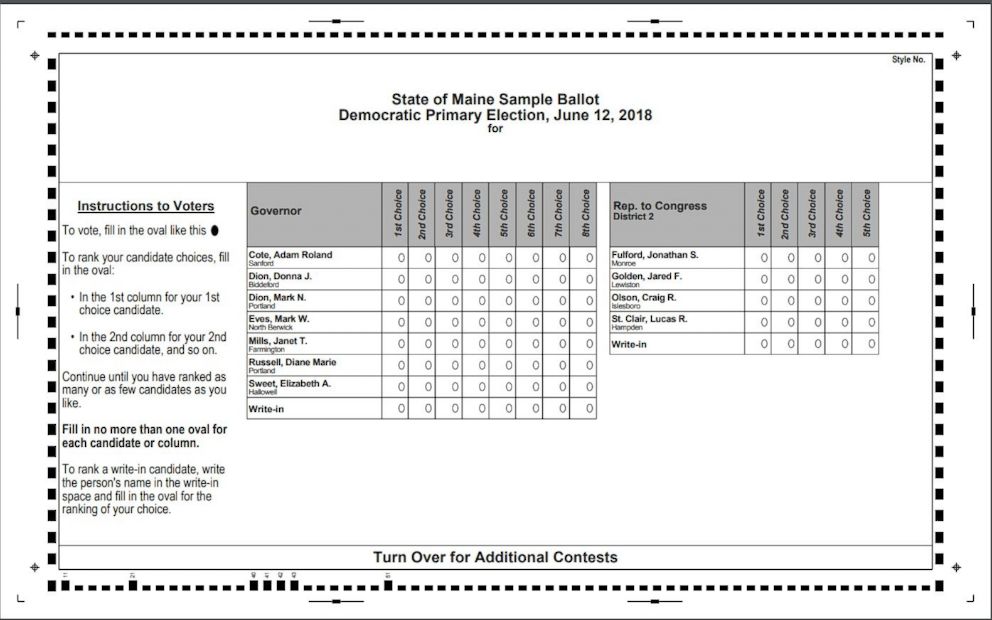

Voters in Maine head to the polls Tuesday as their state joins four others in holding primary elections, but unlike those casting ballots in Nevada, North Dakota, South Carolina and Virginia, Mainers will select their candidates via an emerging system known as ranked-choice voting, which, ironically, could face its elimination on the same day it is finally utilized in a statewide race for the first time.

Ranked-choice voting was approved by Maine voters in 2016 after a string of 11 gubernatorial races in which the ultimate winner received a majority of the vote – over 50 percent – just twice. In the other nine instances, including both general election victories by incumbent Gov. Paul LePage, the winner received a plurality of the vote – the highest total among multiple candidates but less than 50 percent.

Under a ranked-choice system, instead of selecting one option in a field with more than two entrants, voters order the candidates from most-preferred to least-preferred. If no single candidate receives a majority of the vote, the candidate with the smallest number of first-choice votes is eliminated. The ballots for that candidate are then transferred to the candidates selected second by the voters who lost their first choice.

Using the example in the graphic above, no candidate in the field of five received more than 50 percent of the vote in "Round 1" of voting. Under the voting systems most commonly used across the United States, "Candidate C," would be declared the winner with 35 percent – a plurality, or the highest total among the entrants. However, in a ranked-choice system, when no candidate receives a majority, an instant-runoff situation is created. In this example, "Candidate E" is eliminated and the votes of those who chose "Candidate E" first are transferred to their second choice. The process is automatic, no additional election takes place, and it continues until one candidate receives more than 50 percent.

Under the system, it is possible for a candidate, who would not have been the winner under a structure that rewards a plurality, to ultimately win the election should unsuccessful candidates' supporters largely select that nominee as a second or third choice. Such an outcome is also illustrated in the graphic above.

While the system is somewhat rare within the U.S., its advocates argue that it results in the winner being a candidate generally approved of by the widest swath of the voting population.

"We're trying to get representative outcomes – trying to get as many voters to determine the outcome as possible," said Rob Richie, the president and CEO of FairVote, a non-partisan organization that advocates for election reforms.

Ranked-choice voting eliminates the possibility of what Richie termed a "wrong outcome," a result in which a candidate opposed by a majority wins by having the largest vote total – though still less than a majority – in a crowded field. In another way to explain it, it eliminates the role of spoiler, by which generally acceptable third or fourth candidates siphon votes from a leading contender who may win in a head-to-head matchup with their foremost opponent.

For critics of the controversial LePage, ranked-choice voting's earlier utilization may have led to an avoidance of his two terms as governor.

LePage won election in 2010 with 37.6 percent of the vote in the November general election, while second and third place finishers Eliot Cutler, an independent, and Libby Mitchell, a Democrat, combined for 54.7 percent of the vote. In 2014, LePage was reelected with 48.2 percent while Democrat Mike Michaud combined with Cutler, again running as an independent, for 51.8 percent.

That potential aside, Richie said that "the ranked-choice winner is often the person who [receives] the plurality of first-choices," making the system a non-factor in many elections.

While the primary elections will be viewed as one of the first widespread tests of the system's viability, Maine voters will simultaneously be deciding on its future. Despite holding the referendum that approved ranked-choice voting just two years ago (it passed 52.1-42.9 percent in November 2016), the Maine legislature approved a law that suspended its implementation until a constitutional amendment on the subject is passed -- an action which would have to occur prior to December 2021.

On Tuesday, voters will be asked whether that law delaying continued use of ranked-choice voting continued use should be vetoed, though the method will need to withstand further legal challenges.

Regardless of the outcome of the so-called "People's Veto," the ranked-choice system will be used in the primary election.

In the meantime, with ranked-choice voting being utilized in nationwide elections in Australia, India and Ireland, and on local ballots in cities such as San Francisco and Minneapolis, FairVote is pointing to bills on the matter being introduced in nearly 20 states "introduced almost equally by Republicans and Democrats" as signs that the system is gaining momentum.

Asked why critics of the system would hesitate to give voters the option to indicate their varying degrees of preference for multiple candidates -- a seeming solution to the electoral logjam seen as recently as last week's California primary in which more than 20 candidates appeared on the gubernatorial primary ballot -- Richie provided a straightforward answer.

"Fear of change," he said.

ABC News' Roey Hadar contributed to this report.