'The Longest Shadow': 20 years later, 9/11 families seek justice -- and peace

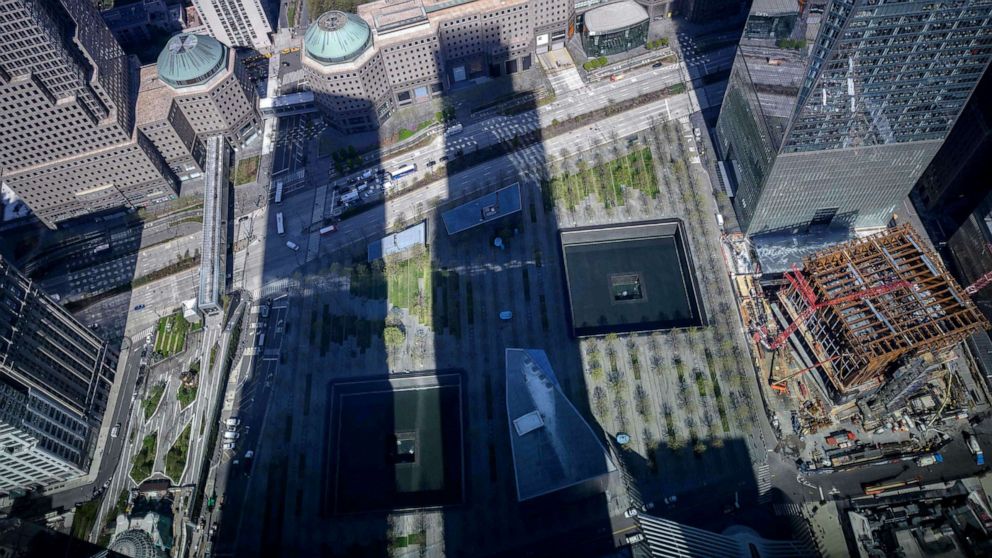

The sky was clear and blue. The gray towers stood, both guarding and welcoming, at the gateway to the nation. Out of nowhere came the impact, the blaze, the smoke -- and then the towers were gone. When the dust and flames finally cleared, a new world had emerged.

The death and destruction defined that late summer day and remain seared in the minds of those who lived through Sept. 11, 2001. From the ashes and wreckage rose a new America: a society redefined by its scars and marked by a new wartime reality -- a shadow darkened even more in recent days by the resurgence of fundamentalist Islamist rule in the far-off land that hatched the attacks.

Twenty years later -- with more than 70 million Americans born since the crucible of the attacks -- the legacy of 9/11 remains. From airport security to civilian policing to the most casual parts of daily life, it would be nearly impossible to identify something that remains untouched and unaffected by those terrifying hours in 2001.

This week, ABC News revisits the 9/11 attacks and unwinds their aftermath, taking a deep look at the America born in the wake of destruction. "9/11 Twenty Years Later: The Longest Shadow" is a five-part documentary series narrated by George Stephanopoulos. Episodes will air on ABC News Live each night leading up to the 20th anniversary of the attacks, from Sept. 6-10. The series will be rebroadcast in full following the commemoration ceremonies on Saturday, Sept. 11.

Part 1: Left behind

For all the palpable change 9/11 imposed on American life, accountability and justice for the attacks remain elusive. Families of both victims and heroes are tortured by the unanswered, fundamental questions of how this could happen -- and who was responsible?

"How is it that 19 individuals ... how was it that they were able to pull off the greatest attack in human history?" asks Brett Eagleson, whose father, Bruce, was killed in the attack while on assignment in New York overseeing the development of a retail corridor beneath the World Trade Center.

The issue of responsibility is not the only lingering question. For hundreds of families, including Eagleson's, the remains of their loved ones were never recovered -- adding an additional layer of trauma to the already enormous loss.

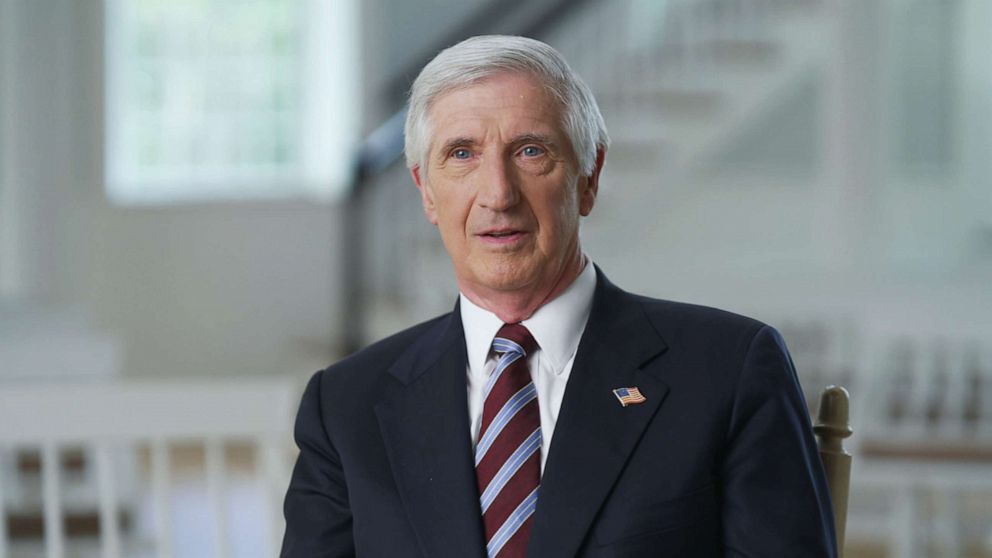

The attacks seemed inconceivable, said Andy Card, chief of staff to then-President George W. Bush.

"Nobody thought that a commercial jetliner would be hijacked and then used as a weapon of mass destruction with a suicide pilot who was willing to sacrifice his life to take thousands of other lives," Card said.

The plot was equal parts simple and sinister: On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, hijackers boarded four separate California-bound flights, strategically targeting coast-to-coast planes because they would be heavily loaded with fuel. The terrorists booked first-class tickets due to their proximity to the cockpit. Within two hours, aircrafts struck both World Trade Towers in New York and the Pentagon outside of Washington, D.C. A fourth and final plane careened into a Pennsylvania field after passengers tried to retake the aircraft from hijackers. It is believed that the hijackers had put that final jet on a trajectory to crash into either the White House or the U.S. Capitol.

At the White House, there was confusion and chaos as most staffers were evacuated while key national security officials frantically tried to assess what was happening and whether anything could be done to stop it.

"At the time, we thought there might've been as many as 11 planes hijacked," said Roger Cressey, a senior member of the White House National Security Council at the time.

In New York City, there was horror and desperation as people ran from the World Trade Center's gigantic towers. Others, doomed on the floors above those struck by the hijacked jets, leapt from the buildings in a futile attempt to escape the flames and smoke.

Watching the events unfold on TV, Americans at first hoped that the horror at the Twin Towers was just a terrible accident -- the result, perhaps, of an errant pilot who suffered some sort of catastrophic medical emergency. Soon, though, reality became clear.

"It was an attack," said Tom Ridge, who was governor of Pennsylvania on Sept. 11 and would soon after be tapped by President Bush to lead the new American "homeland security" infrastructure. "You didn't have to be a counterterrorism expert to know that evil was afoot."

The heroes that morning were the first responders. A staggering 441 emergency workers were killed when the twin towers collapsed -- including Moira Smith, who was the only woman among the 23 NYPD officers who were killed that day.

"A lot of people have told my family that she was obviously a really big part of why they made it out that day," said Patricia Smith, Moira's daughter, who was two years old on 9/11. Patricia has no memory of her mom, but has crafted a detailed picture in her mind from the recollections of her family.

It was Moira Smith who called in the first reports of an incident at the World Trade Center, and witnesses said she guided hundreds of people to safety as the towers burned. Her badge and remains were recovered from the rubble of Ground Zero six months after the attack.

But scores of families received no such closure. As of 2019, over 1,100 families had loved ones still officially listed as missing, without any remains identified -- including the family of Bruce Eagleson.

"We've never recovered him, not even a trace," said Brett Eagleson, who was 15 when his father died. "But at some point, you sort of just have to make a decision to accept the fact that he's lost."

That open wound has driven the New York medical examiner's office in its ongoing effort to identify remains. Twenty years after the attacks, a committed team of forensic scientists continues to recover DNA samples using ever-improving technology.

In the years since the attacks, Eagleson has turned his focus toward one of the great enduring mysteries of 9/11: who aided and abetted the al-Qaeda attackers. Eagleson and thousands of other family members of those killed on 9/11 are pursuing a class-action lawsuit against the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia -- a key American ally in the Middle East that nonetheless produced Osama bin Laden and most of the 19 hijackers.

Their 2017 lawsuit seeks to hold the kingdom accountable for its alleged complicity in the attacks. The protracted legal dispute has hit a series of snags in the federal court system, but attorneys for the victims' families recently conducted a series of depositions with Saudi officials, according to court records.

In 2004, the bipartisan 9/11 Commission concluded there was "no evidence the Saudi government as an institution or as individual senior officials knowingly support or supported al Qaeda" -- a finding the Saudi government has relied on to absolve itself for the last 17 years.

But many remain skeptical of that conclusion. John Farmer, a senior counsel to the 9/11 Commission, cautioned that investigators at the time may not have had a complete picture of the Saudi role -- and suggested that rogue elements within the Saudi government could well have been more active than the FBI and other agencies understood in the first months after the attacks.

"If there were Saudi officials who, in their spare time, were working with elements of al-Qaeda, that would not surprise me at all," Farmer said.

On Sept. 3, President Joe Biden issued an executive order directing the Department of Justice, the FBI and other government agencies to determine what -- if any -- classified records connected to 9/11 can be released. The order instructs the attorney general to release the declassified records within the next six months.

Eagleson believes that the 9/11 Commission's conclusions were erroneous and that the U.S. government knows more than it is sharing with the American public.

"It's really important for the people of this country, for the people of America, to know that the 9/11 Commission ended in 2004," Eagleson said. "The FBI continued to investigate the Saudi role in 9/11 until 2016 under the secret operation called Operation Encore."

Yet the U.S. government's unwillingness to share key documents tied to Operation Encore and other probes -- dating back several administrations -- has become a major roadblock for litigants.

"Because of the classification on intelligence, I'd have to tell you that the American people probably aren't aware of everything that is involved," said Leon Panetta, the former defense secretary who, as CIA director in 2011, oversaw the mission that led to the killing of bin Laden in Pakistan. "Not to say that there's something super-secret, but … we think there were those that knew what bin Laden was up to, and that knew the dangers that were involved."

Kenneth Williams, a retired FBI agent who wrote a now-famous memo warning of al-Qaeda's capabilities just months before the attacks, is now working with the families suing the Saudis -- against the wishes of the FBI, which instructed him to refrain from directly contributing to the suit.

"This is a murder investigation," Williams said. "This case needs to be solved."

In August, the Biden Justice Department promised it would release a bevy of relevant documents, which family members say will be a major step toward accountability. But the damage that's already been done -- and the amount of time that's passed -- remains a source of frustration for relatives of the victims.

"Justice delayed is justice denied," said Patricia Smith. "And now we're 20 years later with no justice."