How a DNA database's new policy is changing police access and could hinder solving cold cases

A change to GEDmatch, a third-party genealogy site that's helped crack cold cases through user's DNA, may hinder law enforcement's ability to use the database to catch killers.

Now, GEDmatch participants will have to upload their personal DNA to the database and manually "opt in" if they want law enforcement to have access to their information, co-founder Curtis Rogers told ABC News on Tuesday. Users will no longer be "opted in" automatically.

This change -- which Rogers calls more fair and upfront -- took effect Sunday.

Rogers acknowledged GEDmatch had received complaints, but declined to discuss the other reasons why the decision was made.

"Ethically, it is a better option," he said. "It's the right thing to do."

How does GEDmatch work?

GEDmatch got on the public radar in April 2018 after the suspected "Golden State Killer" became the first public arrest through the use of the database and a DNA-and-family-tracing technique known as genetic genealogy.

Through genetic genealogy, an unknown killer's DNA from a crime scene can be identified through his or her family members, who voluntarily submit their DNA to GEDmatch or another genealogy database. This allows police to create a much larger family tree than using law enforcement databases like the Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, in which an exact match is needed in most states, according to genealogy expert CeCe Moore.

Direct-to-consumer DNA companies, including AncestryDNA and 23AndMe, do not allow their DNA samples to be searched by authorities, Moore said.

Those companies, however, do allow users to download their raw data, Moore said. And third-party genealogy databases like GEDmatch permit people to upload their DNA information, she said, making the samples widely available for searches -- and that's how genetic genealogists have been cracking these cold cases.

Since the arrest of the suspected "Golden State Killer," over 50 suspects have been identified through the technology, according to Moore.

'It could leave a murderer running on the streets'

GEDmatch's new policy requiring participants to manually allow law enforcement access to the information will make it harder to solve crimes, according to one police officer.

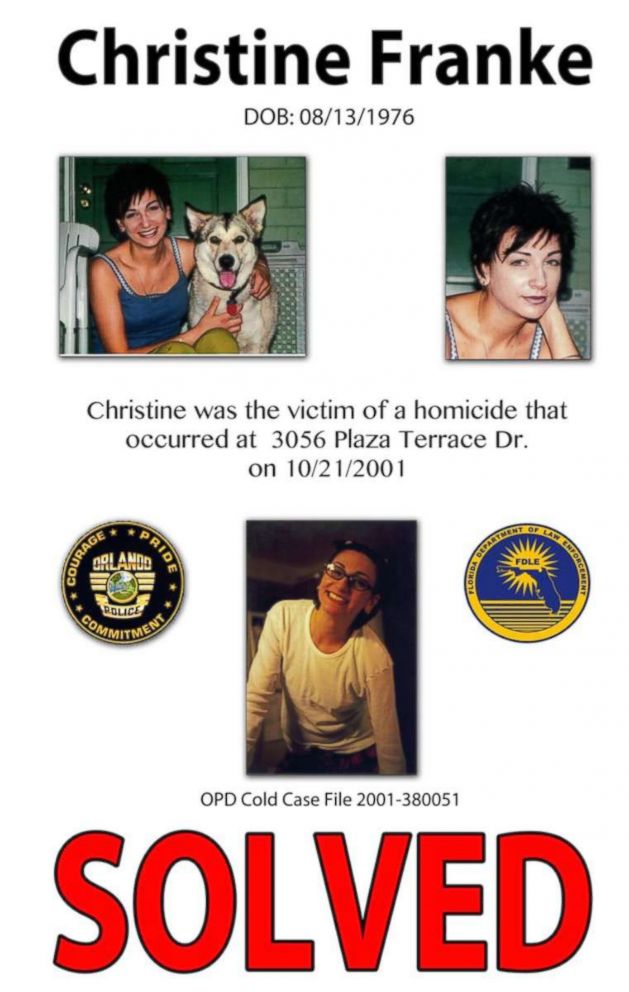

Michael Fields, a detective with the Orlando Police Department, used genetic genealogy to crack the murder of 25-year-old Christine Franke after 17 years.

The young college student was shot dead in her Orlando apartment on Oct. 21, 2001. Though DNA was left behind at the crime scene, years went by without an arrest.

In November 2018, after police say they used the unknown killer's DNA to trace a family tree through GEDmatch, a suspect was arrested.

Christine Franke's mother, Tina Franke, said if users don't want law enforcement to have access to their DNA, they shouldn't upload their information to GEDMatch in the first place.

"If it wasn't for this genealogy and the DNA, there would've been no way they would've caught this man. He'd been under the radar for 17 years," she said. "I'm thankful [the police] had access to it... I think the police should be able to use it regardless."

"It's going to make our cases a lot harder to solve," Detective Fields told ABC News of GEDmatch's new policy. "It's a shame it could leave a murderer running on the streets, but I perfectly understand why they'd want to change that."

"Everything that we do in law enforcement, we're always adjusting to new standards and new rules," he said, "so it's something that we'll just have to adjust to."

Fields also noted that GEDmatch isn't the only database in the game anymore.

"GEDmatch was the one that got everything started, but there are other companies that are trying to assist in solving crimes," he said.

'A setback for justice'?

Moore, who is the chief genetic genealogist at Parabon -- a lab involved in most of the cases solved through genetic genealogy -- called GEDmatch's new "opt in" policy "a tragedy for the families who would have gotten answers and, perhaps, justice in the coming months."

"Further, it is very likely to cost lives," Moore told ABC News via email Tuesday.

"It will take a significant amount of time to build the opt-in database to a level that will be able to address the number of cases we were able to last week and we will never regain some of the data since many in the database are deceased and/or have abandoned accounts," Moore said. "Whatever one thinks about this decision, it is inarguable that it is a setback for justice and victims and their families."

Vera Eidelman, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), told ABC News via email, "GEDmatch’s decision is a good and important step—but it is not a decision that should be up to a private company. Lawmakers and courts need to step in."

"Our DNA is deeply personal. Unlike a fingerprint, it can reveal far more than our identity," she said. "Moreover, the information held by GEDmatch and similar companies can reveal such personal details not only about their users, but also about dozens if not hundreds of those users’ family members. The government should not be able to access that information about us without our consent."

But Rogers, the GEDmatch co-founder, said he "absolutely" supports law enforcement's use of the database "because of the victims and because of their families and the survivors."

He said he's received many letters of gratification after GEDmatch was involved in finding suspects in rapes and murders.

"We're very anxious to get as many people opting in as possible... as fast as possible," he said.