Latinos, many with essential jobs, disproportionately affected by COVID-19

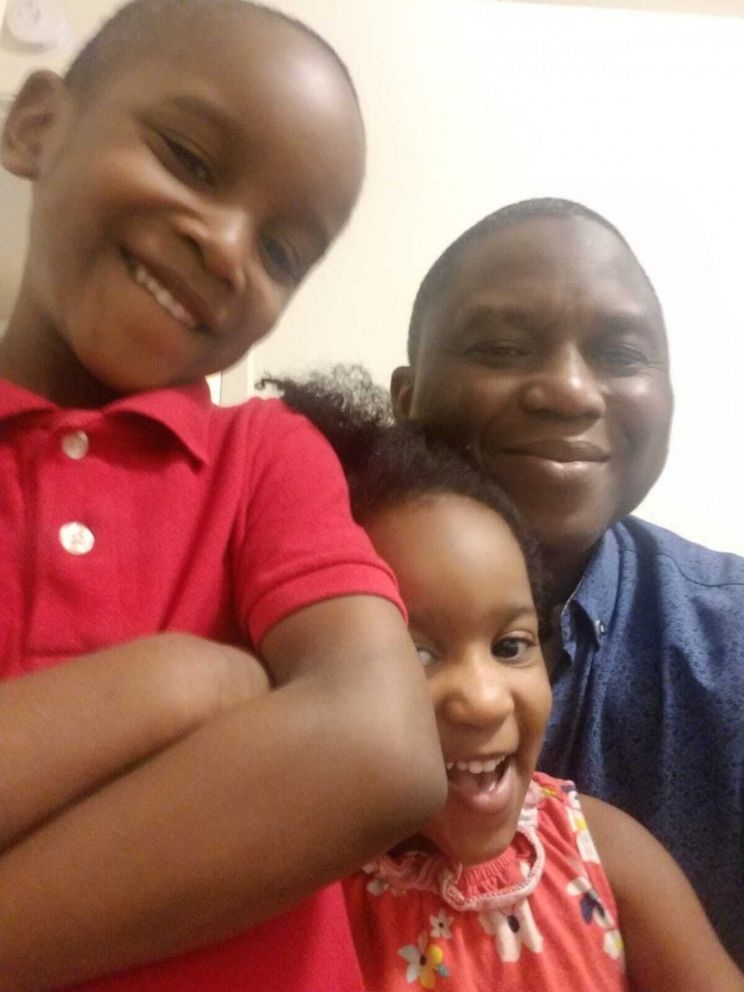

For years, the highlight of Candido’s day has been returning home from work to his wife and children, Caleb and Emma. He has carried the pride of his job as an essential worker in the construction industry.

That was until he brought COVID-19 home.

“The first symptom was at work. I felt different types of chills. Then my legs felt shaky," Candido, who asked to be identified by only his first name, told “Nightline” in Spanish.

Although Candido doesn't know if he contracted the virus at work, he says he became ill in early June. He eventually lost his senses of taste and smell and says he feared for his family. His wife and children all have asthma, and he worried about how they would be impacted if he passed the virus to them.

“We were going to be in an economic situation where we wouldn’t be able to pay the rent,” he said. “We don’t have any support. We didn’t know if the sickness was going to affect us or if we would end up in the hospital. If we were going to die, what was going to become of our kids.”

It is a situation many essential workers across the country are dealing with every day. They keep our country’s economy running amid a pandemic, despite their vulnerabilities to the virus.

Now, so many people like Candido are forced to weigh the fears of transmitting the virus and still providing for their family or staying home without being able to earn a living.

“My fear is that at any moment I could get contaminated again and bring the sickness home and that it turns out to be catastrophic,” Candido said.

Nearly four months into the pandemic, at least 40 states are now reporting a surge in COVID-19 hospitalizations.

“This is the greatest public health crisis that our nation’s faced in more than a century,” Dr. Robert Redfield, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told ABC News. “We’re very new in learning about this virus so it is very hard to predict. Clearly though, we have a significant upsurge of the outbreak now.”

As the numbers continue to rise, a clear picture of those most affected is emerging.

Nationwide, Hispanic people now account for nearly a third of all COVID-19 cases.

In Texas, where Candido lives, the majority of construction workers are Latino like him. He said that in early June he became so sick with the virus that he went to the hospital. A native of Honduras, Candido is undocumented and uninsured. He feared his immigration status would impact his treatment.

“I did get worried that I would end up at the hospital connected to a ventilator,” he said. “Because I’m an immigrant I wondered if they would remove me from the ventilator to give it to a U.S. citizen. That really worried me.”

Candido said he was sent home to recover, quarantining without sick pay. He said he received a hospital bill for $7,000 a few days later. He says the hospital has reduced the bill down to $3,500, forcing him into credit card debt. He says he had to borrow money from relatives in Honduras.

“Not being able to work meant I wasn’t going to have a salary,” he said. “It won’t allow me to pay the bills.”

For Candido, no work truly means no pay. Due to his immigration status, he has been ineligible for the stimulus check provided under the federal government’s Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act and he cannot apply for unemployment benefits.

Candido soon passed the virus to his wife, which forced both of them to distance themselves from their own children.

“It’s not easy because you want to hug and kiss them,” he said of his kids. “They ask for it and it’s sad because you can’t do it.”

He said that when it comes to the construction industry, employers should care for their employees. Instead, he says, the responsibility to protect themselves often falls on the workers.

“They aren’t giving the tools to protect us,” he explained. “They say, ‘Bring a mask’ but they don’t provide masks. The employee has to bring their own mask. The employee needs to come with their own gloves, and that should be provided by them and they don’t do it.”

His experience is just one of many illustrating COVID-19’s disproportionate and growing grip on the Latino community.

In Chattanooga, Tennessee, the latest census shows Latinos make up only about 6% of the population. Yet, 40% of all COVID-19 cases in the city are Latino.

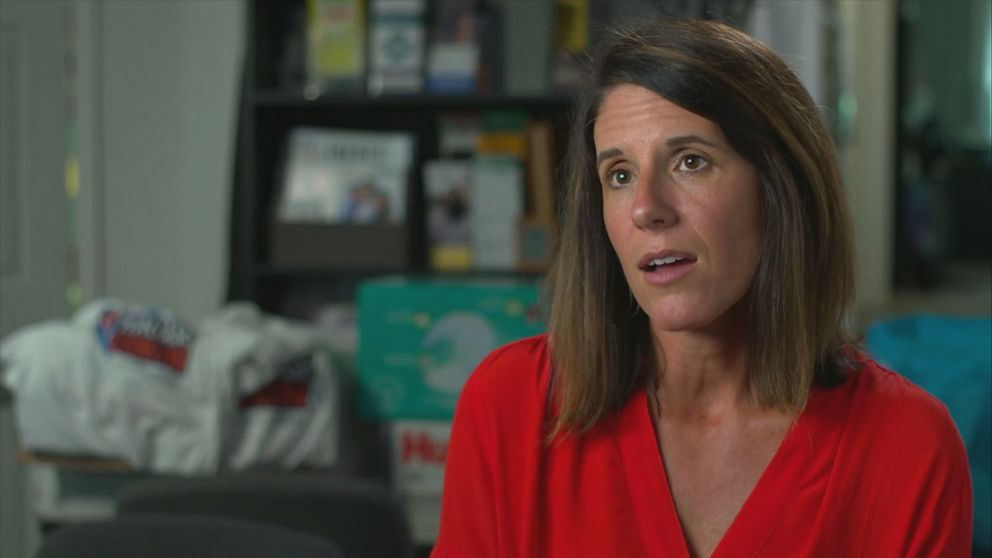

“We knew that the Latinx population would be hit, but we didn't know it would be hit so hard,” said Stacy Johnson, the executive director at La Paz Chattanooga, a nonprofit serving a growing Guatemalan and Mexican community.

Local organizations like La Paz have now joined forces to help and support this community.

“From day one when COVID-19 came to Chattanooga, we knew that the Latinx population would be hit,” Johnson said. “We knew … the majority of them were essential workers.”

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the calls were already coming in.

“We've gotten lots of calls from … a wife, for instance, that her husband works in the construction field. She and the children have stayed home,” Johnson said. “She's afraid because she knows that her husband is at risk every single day. We have had calls from people in the service industry now that restaurants and hotels are starting to open back up.”

Johnson says she knew it was too early when the state began to reopen on April 30, and that local officials made the decision without prioritizing the growing outbreak in the Latino community.

“I don't feel like any of those entities recognize the Latino community wasn't part of the strategy. It wasn't part of the plan,” Johnson said. “They only noticed this population subgroup when the numbers increased… Honestly, it was a little too late.”

Johnson’s group has focused on providing much-needed information on COVID-19 in Spanish -- information she says has been lacking from city and state institutions.

“We feel like language is a huge barrier -- language and culture,” she explained. “We made sure that anything that was going out to the community was available in Spanish. We have a large Guatemalan community here and many of them speak a Mayan language. [We’re] making sure that even those community members can have access to this really important information.”

Johnson says stay-at-home orders have been a challenge, especially for the city’s essential workers, who are undocumented and unable to get sick pay. Often, the only support comes from private relief funds donated by organizations like La Paz.

“A large percentage of the Latinx population are not eligible for any sort of government assistance. They're not eligible for the stimulus package,” she said. “If we're not able to provide financial assistance to this population, they will continue to work because [no income] is a much bigger challenge than maybe catching the virus.”

Dr. Kelly Arnold, who runs Clinica Medicos in Chattanooga, says this pandemic is “like nothing” she’s seen in the last 15 years. She is now part of the city’s coronavirus task force.

“As a family physician and a community physician, [I’m] really grappling with how do we, beyond the test results, stabilize families inside of such a vulnerable situation,” she told “Nightline.”

“We know by and large that these active measures of socially distancing, washing your hands, wearing a mask ... those seem simplistic in nature, but [what] if your job and your vitality depends upon being rubbed up against someone’s elbows to be on an assembly line or in a kitchen,” she said. “Not only that, [but] your employer might not be providing you with adequate [personal protective equipment], then the decision is, ‘What do I do for my family?’ And most times, people are going to decide to protect your family economically.”

Compounding it all, many of Arnold’s patients are uninsured and undocumented, meaning they can’t get sick pay.

“I realized that when jobs shut down and jobs end, especially [in] the uninsured community, the first thing to go is people taking care of themselves and prioritizing their health care,” Arnold said. “That is one of the things that they set aside to save, to keep a roof over their head, to feed their children.”

“The weight of that moment is incredible,” she added. “‘Am I going to be on a ventilator? Am I going to die? We're undocumented. What's going to happen?’ All of these ponderings are palpably present in the lives of our patients and we see it every day.”

Betty Delgado, a Mexican immigrant, said paid sick leave made it easier for her to stay home and recover after she tested positive for the virus.

Delgado cleans homes for a living. She said her mother works at a chicken processing plant and her father, now retired, babysits her children. She said it only took one person to get sick to force everyone to stop working. It started with her father. Delgado, who says she has diabetes and kidney issues, eventually started feeling symptoms -- first a fever, and then a cough that knocked the wind out of her.

“I was so scared that I would die because every time I coughed I felt like my heart would stop from so much coughing,” Delgado said in Spanish. “I lost all my strength.”

Delgado and her parents have now recovered from the virus and gone back to work. Still, Delgado says she is far from feeling safe.

“I’m trying to take care of myself now because I don’t want to relapse,” she said. “I feel safe when I’m in my house, but when I go out to buy food, I don’t feel safe because people aren’t careful… No one knows who is infected or who isn’t.”

Despite her fears, Delgado and her mother are back to work. It’s a risk for her, but not a choice, for another employee both essential to her family and our country.

This report was featured in the Friday, July 24, 2020, episode of “Start Here,” ABC News’ daily news podcast.

"Start Here" offers a straightforward look at the day's top stories in 20 minutes. Listen for free every weekday on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, the ABC News app or wherever you get your podcasts.