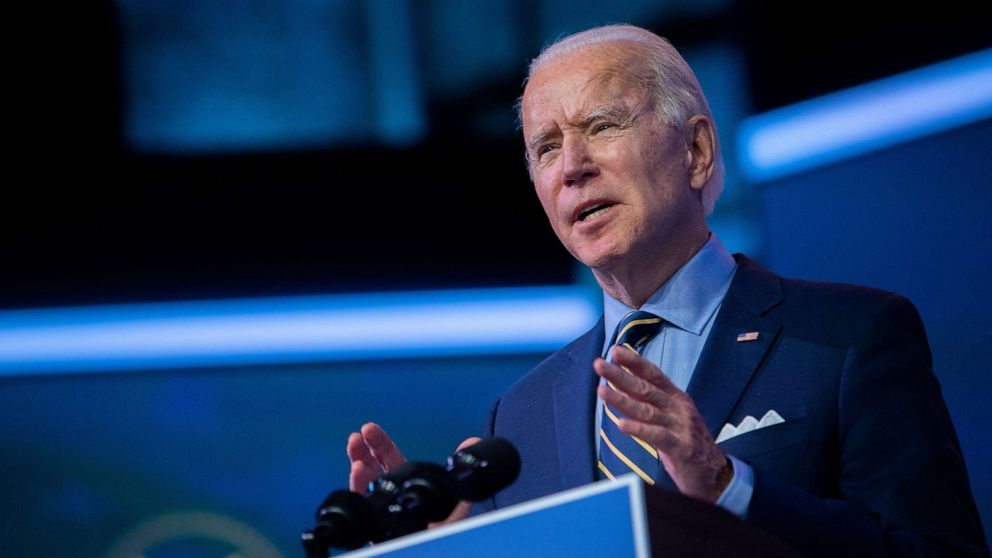

Joe Biden's top foreign policy challenges in 2021

When Joe Biden takes office as the 46th president, it's clear his agenda will focus on the challenges at home. His slogan to "Build Back Better" was centered around handling the coronavirus pandemic, rebooting the U.S. economy, and tackling systemic racism and economic inequality.

But the challenges facing the U.S. and the world will not wait. From Latin America to East Africa, nuclear-capable rogue states to revanchist regional powers, the Biden administration is sure to face foreign policy crises as it tries to address those domestic issues.

"The preponderance of the focus will have to be internal," Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, told one of CFR's podcasts in December. "The president is going to walk into a really demanding situation domestically and internationally, and my instincts are ... he has got to deal with repair work, rather than think of it as a major innovation phase."

That repair work was the heart of Biden's foreign policy pitch, talking repeatedly on the campaign trail of working on America's alliances, particularly in Europe and Asia, and on American leadership at the World Health Organization, in the Paris climate accord and elsewhere on the world stage. But while that kind of steady work is underway, Biden is likely to face a North Korean long-range missile test, continued Russian and Chinese cyber attacks, or Iranian provocations in the Persian Gulf -- requiring him to prioritize and delegate.

"The failure to prioritize is almost always a bigger problem than not doing enough on the lower priorities on your agenda," said Kori Schake, director of foreign and defense policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute. "The fact that the edges fray and that some things don't get attention and things ought to have worked better in other places -- that's the cost of doing business."

Restore alliances, compete with China

At the top of Biden's list, then, should be a one-two punch, according to Schake: "Cajoling America's allies into alignment to manage a rising China together."

The Trump administration identified China as the greatest long-term threat to the U.S., a position around which there is growing bipartisan consensus in Washington. China has shown more assertiveness in the region -- expanding its military presence in the South China Sea, battling Indian troops in the Himalayas and harassing Taiwanese armed forces with greater frequency -- and greater repression at home, especially against Hong Kong and Muslim Uighurs. Its years of economic espionage and intellectual property theft have met a backlash that's now bordering on "decoupling," separating supply chains and economies.

Biden has said he may keep some of Trump's tariffs in place and expand human rights sanctions, but he's also expected to take a different tact than Trump's strong-arm, "America First" strategy that, at times, alienated U.S. allies.

"The Trump administration pitched so many needless fights," said Schake, including over U.S. troops in Japan, South Korea and Germany and national security tariffs on Canada and the European Union. "That will be an enormous challenge for President Biden and his team to reset those relationships back into effective and cooperative patterns."

Antony Blinken, Biden's pick to be secretary of state, has said those alliances are key to solving "the big problems that we face as a country and as a planet -- whether it's climate change, whether it's a pandemic, whether it's the spread of bad weapons."

Biden hopes too, according to Blinken, that the strength in those numbers can boost the U.S. hand against China and force cooperation on those bigger issues.

"We're much better off though finding ways to cooperate when we're acting from a position of strength than from a position of weakness," he told the Hudson Institute in July.

Reining in Russian aggression

While China's push for territory and influence is a long game, Russian aggression may provoke a more short-term response.

Vladimir Putin has used chemical weapons to poison domestic opponents like Alexei Navalny and even on foreign soil, like Sergei and Yulia Skripal in the United Kingdom. His cyber army has repeatedly breached U.S. government and private sector systems, most recently with the massive SolarWinds hack that has breached government agencies and the private sector. With the last nuclear arms pact between the U.S. and Russia set to expire on Feb. 5, Biden will face the immediate challenge of arms control with America's greatest nuclear competitor. And Russian military forces and mercenaries have their hand in conflicts from Syria to Libya, the Central African Republic to Venezuela.

Biden is expected to take a harder line than Trump, who has backed Putin's claim that he did not interfere in the 2016 elections, welcomed his decision to expel U.S. diplomats and cast doubt on Russia's role in the SolarWinds hack. But Biden will likely continue many of the Trump administration policies, including sanctions over Russian aggression against Ukraine, in Syria, online and with chemical weapons.

That's exactly what the Kremlin expects. Putin's spokesperson said last week that they anticipate "nothing positive" from the change in U.S. administrations.

That could give Biden an opportunity, however, because his administration "will be the first in the post-Cold War period that did not have unrealistic expectations concerning Russia, and in some sense that is a positive sign," according to Victoria Zhuravleva, professor of U.S.-Russian relations at the Russian State University for the Humanities in Moscow. But relations will largely be driven by each country's domestic politics, Zhuravleva added, leaving "no room for optimism."

North Korea has more nukes

Shortly after landing from his first summit with Kim Jong Un, Trump declared on Twitter, "There is no longer a Nuclear Threat from North Korea."

This October, Kim's regime paraded a 75-foot-long missile through the streets of Pyongyang. It hasn't been tested yet, but the massive weapon is most likely an intercontinental missile that could reach the U.S. mainland with multiple nuclear warheads, according to analysts.

Trump's confidence in his personal diplomacy with Kim has not only failed to disarm Kim, it's also given the young leader time to build more nuclear weapons and perfect his ballistic missile capability, with short-range tests that violated U.N. resolutions, but were dismissed by Trump.

"The Biden administration will be finding itself with less bargaining power than Trump had in Hanoi, given the impressive progress North Korea has made in developing their nuclear weapons and missiles," former CIA Korea analyst Sue Mi Terry said in November on a podcast by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, where she's now a senior fellow. "We have to now look at the possibility of an interim deal that at least freezes their program."

Biden has said he would negotiate with Kim's regime, but not Kim himself, until working-level negotiators had reached at least an interim deal. It's unclear if he'd accept that kind of short-term deal to open the door to a longer-term solution, but some analysts argue it's the only way forward given the deep mistrust on both sides.

In the meantime, Biden said he will work to shore up the U.N. sanctions against Pyongyang, especially after increasing violations by neighboring China. But given high tensions between Beijing and Washington, it's unclear how much help he will get, even if Kim tests a long-range missile to steal attention in Biden's early days.

Iran troubles the water ahead of talks

Biden will have to deal with an Iran that has enriched more uranium at higher levels and with more advanced centrifuges than when he left the vice presidency. Its economy, however, is in a deep recession because of Trump's sanctions, with its economy contracting by 6.8% in 2019-2020, according to the World Bank.

"If Iran returns to strict compliance with the nuclear deal, the United States would rejoin the agreement as a starting point for follow-on negotiations," Biden said in a CNN op-ed in September. "With our allies, we will work to strengthen and extend the nuclear deal's provisions, while also addressing other issues of concern."

Iran has signaled, however, that won't be possible. Its leaders, including President Hassan Rouhani, who is term limited and set to leave office in June, have said not only will they renegotiate the terms of the nuclear accord, but also that Iran must be compensated for the economic damage of Trump's sanctions.

In December, its parliament also passed legislation to increase uranium enrichment and expel U.N. nuclear inspectors if oil and banking sanctions aren't lifted by early February -- moves that would tip the situation toward nuclear crisis. Already, it has moved to enrich uranium to 20%, which is a short step from weapons-grade levels.

In addition to nuclear blackmail, Iran may initiate attacks on oil tankers in the Persian Gulf or rocket fire on U.S. facilities in Iraq, using that tension to also try to build leverage -- and put Biden in a tough political situation to respond.

It's not just Republicans in Washington that will pressure Biden. Opposed to the original nuclear accord, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, among others in the region, will want to have a say in whatever new deal may be negotiated -- while Biden is expected to push back on these U.S. partners after four years of cozy relations with Trump.

Addressing climate change and migration

Biden has made clear that addressing climate change will be a top domestic and foreign policy priority, especially with the appointment of former Secretary of State John Kerry to a Cabinet-level, special envoy role.

"The world will know that with one of my closest friends, John Kerry, he's speaking for America on one of the most pressing threats of our time," Biden said in November. "No one I trust more."

But the growing climate crisis will require more than the commitments on paper that Kerry helped secure in the Paris climate accord in 2015. The global temperature in 2020 is on track to end about 1.2 degrees Celsius warmer than the end of 1800s, according to the U.N.'s World Meteorological Organization, dangerously close to the 2-degree cap scientists have warned could tip much of the world into unlivable conditions.

Another risk for Biden is letting Kerry's diplomacy efforts interfere with Blinken's. The utmost importance Kerry places on climate change, seemingly above other critical issues in the U.S.-China relationship, could undermine Blinken's work on economic espionage or human rights, for example.

"It could give Beijing an incentive to withhold cooperation on climate unless it receives concessions on other issues," according to Thomas Wright, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Kerry has also said mitigating the effects of climate change is key to issues of migration.

"People are going to move to places where they think they can live. They'll fight over places that they want to move to. We will have millions -- tens of millions of climate migrants," he told ProPublica this fall.

Working with countries in the Western Hemisphere, especially Mexico and the so-called Northern Triangle of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, will be critical to addressing immigration, which could surge as Biden lifts Trump's severe policies at the border, on asylum and for visas. Kerry has described that as an opportunity, especially to solidify relations with neighbors Mexico and Canada -- and one that some analysts say could expand to critical issues like supply chains and trade.

Ending America's wars, without raising terror threat

Among the first issues Biden will have to deal with is the U.S. military presences in Afghanistan and Iraq, where Trump has drawn troops down to just 2,500 in each country after nearly two decades of fighting.

"The Trump administration gave the Biden team an incredible gift by recklessly drawing down American military forces and political engagement in Afghanistan and in Iraq because near as I can tell, President Biden and his team have the exact same policy that they want to undertake, and the Trump administration will now get all the blame for the obvious consequences of it," Schake told ABC News.

Biden has not been clear about what he would do with U.S. troops in either country, but he's signaled he would at least slow full withdrawals. In Afghanistan, he's indicated he would work to hold the Taliban to its commitments under Trump's deal with the militant group, but focus U.S. forces on al-Qaida and the Islamic State.

The key questions are what will Biden do if violence threatens to engulf Afghanistan or if negotiations between the Taliban and Afghan government fall apart, and how to ensure the country doesn't risk becoming a terrorist safe haven again -- a commitment the Taliban made under the U.S. deal that hasn't been kept yet.

Elsewhere, the threat of Islamist terrorism is expanding. ISIS and al-Qaida affiliates are taking advantage of the insecurity and chaos in Syria, northern Mozambique, the Philippines, and across the Sahel, the northern Africa desert region that includes Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso and Nigeria. While Biden is likely to focus on great power rivalries or U.S. allies, the threat of terrorism remains potent.