Joe Biden once pushed for more police. Now, he confronts the challenge of police reform

In 2002, then-Senator Joe Biden wrote an op-ed for the Delaware State News, reacting to an FBI report that the national crime rate was on the rise for the first time in 10 years. Biden cautioned while crime was down in his home state, the country needed to stay alert to the rising rate.

“What works in the fight against crime? It’s simple -- more police on the streets,” Biden wrote.

“Put a cop on three of four corners and guess where the crime is going to be committed? On the fourth corner, where the cop isn’t. More cops clearly means less crime,” Biden went on in the op-ed.

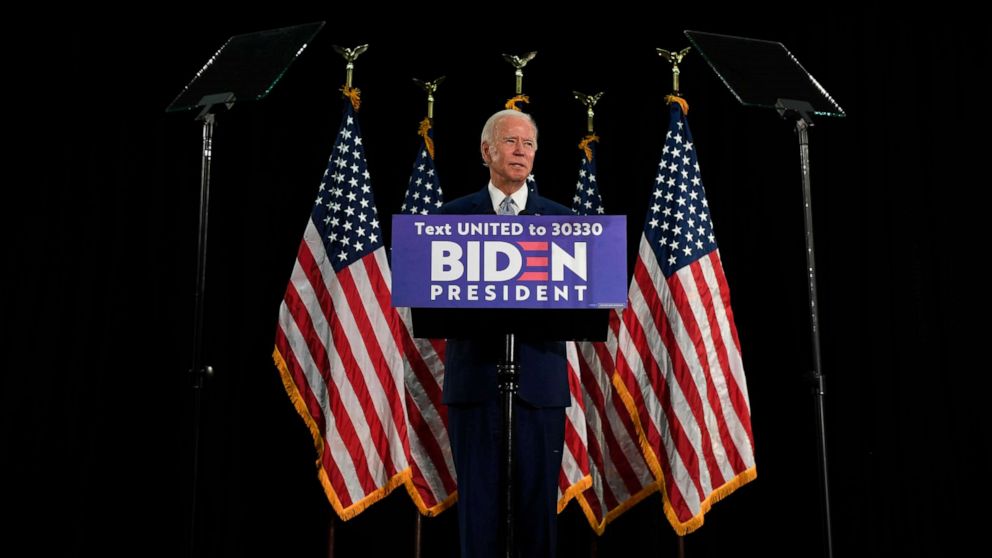

Eighteen years later, Biden is now the presumptive Democratic nominee, mounting his third run for the presidency in the midst of a nationwide discussion on systemic racism, and urgent calls for extensive reforms to policing following the death of George Floyd while in police custody in Minneapolis.

While Biden has called this “one of those great inflection points in American history,” his record on criminal justice, and more than two decades of calls for increasing the number of police on the street are getting a second look, putting his past positions at odds with the conclusions of even some allies.

“We really do have to get to a point where we agree that the status quo way of thinking about achieving safety is really wrong when it assumes that the best way to achieve more safety is to put more police on the streets,” Sen. Kamala Harris, a vice presidential contender and former California attorney general said on Good Morning America Tuesday.

Focusing on the community

Biden’s campaign declined to say if the former vice president still believes that increasing the number of police in communities is the way to ensure less crime, instead pointing to his support for a community-based policing approach.

Recently, Biden has also expressed his support for several measures proposed in legislation introduced by congressional Democrats, including a federal ban on police use of chokeholds, requiring racial and religious bias training for officers, and collecting data on police use of force.

These measures are in addition to Biden’s current plan for criminal justice reform, unveiled in July of 2019, which calls for $300 million in funding for the community-oriented policing, including funding for the Community Oriented Policing Services, or COPS, program, conditioning grants given through the program on the requirement departments hire police officers that mirror the racial diversity of the community they serve.

“I’ve long been a firm believer in the power of community policing — getting cops out of their cruisers and building relationships with the people and the communities they are there to serve and protect,” Biden wrote in an USA Today op-ed published Wednesday on his plan to address systemic racism in policing, which includes reforms like buying body cameras and adopting a national use of force standard.

According to Biden’s campaign, at least a portion of the funding that flows to the COPS program would go to hiring new police, but did not provide specifics on how much of the funding would be allocated for that purpose.

“Those details would have to be worked out in the legislative process, but the funding would likely be used for purposes such as hiring new officers, standing up recruitment programs to ensure officers reflect the diversity of the communities they serve, and training on community-policing strategies,” Stef Feldman, Biden’s Policy Director told ABC News.

Biden’s most recent proposal takes a markedly different tone than his 2008 campaign policy, where he proudly touted his work on the “Biden Crime Bill.”

“In the 1990s, the Biden Crime Bill added 100,000 cops to America's streets,” Biden’s 2008 campaign website read, accessed through an internet archive.

“George Bush's cuts to the program have put America at risk and crime rates are back on the rise...Joe Biden wants to put 50,000 more cops on the street and add 1,000 more FBI agents to address the rise in crime and threats of terrorism,” Biden’s crime policy continued.

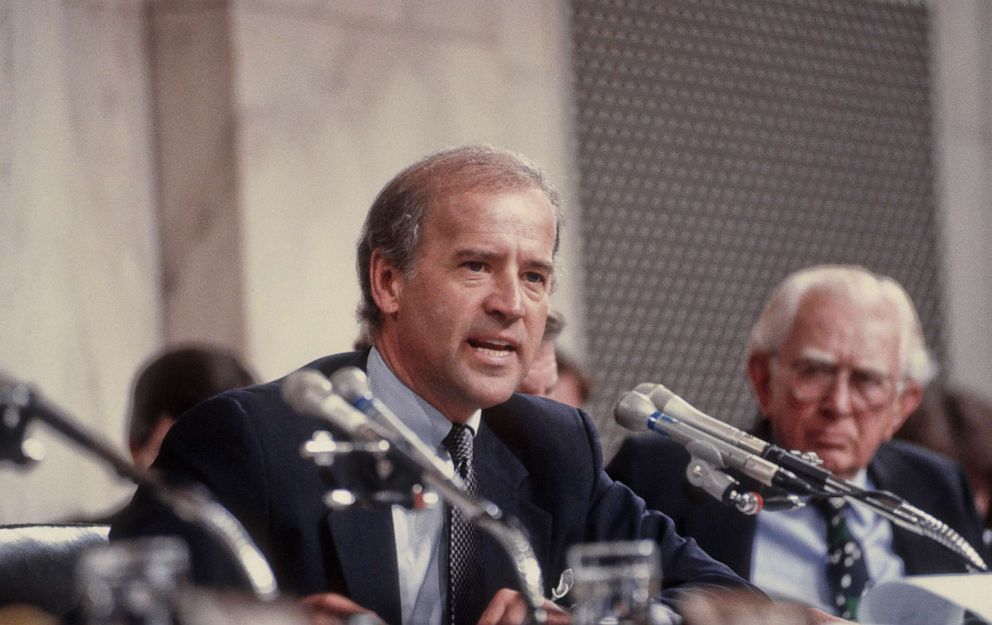

The ‘Biden Crime Bill” and COPS program

Biden has been plagued with questions throughout his third run for the presidency on that measure-- better known as the 1994 crime bill. Despite being proudly touted in his policy proposal in 2008, no mention of the “Biden” bill appears on his current website

The bill, which Biden had a leading role in crafting, encompassed the Violence Against Women Act and a federal assault weapons ban--two largely popular policies with Democrats today.

However, Biden and the legislation have faced intense scrutiny from critics who say it had a disproportionate impact on minorities, and contributed to mass incarceration in the United States. While Biden has defended the bill throughout his campaign, he has also acknowledged portions of the bill were a mistake.

The 1994 bill also created the COPS Program, which initially helped provide grants for hiring new police officers to engage in community policing, and to help train law enforcement officers in “crime prevention and community policing techniques or developing technologies that support crime prevention strategies,” according to a summary from the Congressional Research center.

Biden’s campaign insists that federal funding will not be provided to police departments that do not enact the needed reforms or a community-based model, but some advocates for changes to the criminal justice system still worry that the threat will not deter localities from ultimately using the resources to simply add more cops to the street.

“I don't have any confidence, regardless of what Joe Biden suggests he wants to use the money for, that it will be used in that way. Communities, at the end of the day, they're going to make their own decision about how they want to invest those resources. The thought process in a lot of communities is 'We believe in more cops and we want to build more jails.' And that's really troubling,” Kara Gotsch, the director of strategic initiatives at the Sentencing Project, told ABC News.

Some experts also warn that money that has flowed into the program in recent years, especially during the Trump administration, has not gone towards its purported purpose of promoting community policing in law enforcement.

“Since the program started, billions of dollars have gone to encourage more policing, and far, far less has gone to more community-minded policing,” Rachel Harmon the director of the Center for Criminal Justice at the University of Virginia School of Law told ABC News.

“Any new money to the COPS program should focus on promoting community-based solutions to public safety, and ensuring that departments protect civil rights, minimize harm, hold officers accountable, and allow community input into policing. Otherwise, the money could do more harm than good,” Harmon argued.

Other experts agree that there has been, and needs to continue to be a shift in the way funding for police departments nationwide is allocated and spent, arguing the funding should emphasize meeting the needs of a community and preparing officers for the myriad of challenges they face on a daily basis, and deemphasize the belief that higher incarceration rates will automatically result in better outcomes.

“Funding needs to support efforts to reimagine public safety and how to get there by supporting programs that sometimes divert people away from the criminal justice system. But in order for the police to engage in those more productive public safety-oriented outcomes they need strategies on the ground and resources on the ground to utilize,” said Taryn Merkl, the senior counsel in the Brennan Center’s Justice Program and its Law Enforcement Leaders to Reduce Crime and Incarceration initiative, and a former Assistant U.S. Attorney in the Eastern District of New York.

Biden’s continued focus on community policing has coincided with new calls for defunding police departments from some progressive Democrats in favor of shifting funds away from law enforcement budgets to other priorities to promote public safety.

“No, I don't support defunding the police. I support conditioning federal aid to police based on whether or not they meet certain basic standards of decency and honorableness. And, in fact, are able to demonstrate they can protect the community and everybody in the community,” Biden told CBS News in an interview earlier this week.

The former vice president’s current policy calls for increases in funding to create partnerships between police departments and social workers, disability advocates and mental health and substance use disorder experts, to give police training to de-escalate situations with individuals without turning violent, which could include having social service providers respond to calls with police officers.

Biden also supports “funding for public schools, summer programs, and mental health and substance abuse treatment separate from funding for policing,” according to a Monday statement from campaign spokesperson, Andrew Bates.

“There, I think, is a move to narrow the scope of what police officers should be focused on and really narrow it to focus really on pure law enforcement, when people are committing acts of violence and things of that nature,” Jason C. Johnson, the president of the Law Enforcement Legal Defense Fund, and former deputy commissioner of the Baltimore Police Department from 2016-2018 told ABC News.

“I think that actually kind of works pretty well in community policing because [that’s] what the community really wants. They want a social worker to respond to the problem of homelessness or addiction, not necessarily a police officer.”

Shifting views on criminal justice reform

The reform conversation is also taking place amid a tectonic shift in the public’s attitude on race and policing, borne out in recent polling that has been conducted in the weeks following Floyd’s death.

An ABC News/Ipsos poll conducted last week showed a more than 30-point increase in the belief that recent events reflect a broader issue over racial injustice compared to an ABC News/Washington Post poll from December 2014 that was conducted four months after the shooting of Michael Brown, an 18-year black man, by a white cop, and five months after the death of Eric Garner, a black man, who died after being put in a chokehold by a white officer.

Similarly, a Washington Post poll conducted with the Schar School of Public Policy and Government at George Mason University showed a 26-point increase among American adults in the attitude that police killings of black Americans are part of a broder problem as opposed to isolated incidents, compared to the same 2014 polling.

In the wake of the deaths of Garner and Brown, Biden touted the community-based policing he still supports today as a way to ease tensions between police and minority communities, and advocates, even those who still remain skeptical of his dedication to major criminal justice reform, do credit Biden with a slow but steady evolution of his thinking on the issue.

“He has certainly evolved on criminal justice issues, and started evolving a long time ago. I don't want to suggest that he is sort of the champion for criminal justice reform, but I think he understood. He worked on crack reform. He had the first senate bill to equalize crack and powder sentences,” Gotsch said, crediting Biden for leveraging his relationships with the law enforcement community in 2010 to pass sentencing reform for certain drug-related offenses.

“It was because of him, at the end of the day, that the Fair Sentencing Act passed, which was crack reform. Because he called in his favors with law enforcement and he said, 'I need you not to oppose this. We're getting this done. It's really important.' They didn't oppose it, and law enforcement traditionally is our biggest obstacle to advancing criminal justice reform.”

During Biden’s time as vice president, the White House also placed a strong emphasis on Department of Justice pattern-or-practice investigations to look into systemic police misconduct in local law enforcement agencies and build trust between communities and police -- a tool that has been largely abandoned by the Trump administration, and one Biden’s policy vows to resume.

The broader arc in the conversation around criminal justice and police reform in the country is one the Democratic Party writ large is grappling with.

The 1994 bill that has been the center of considerable criticism was passed with bipartisan support, and had the backing of several Democrats that now occupy the highest echelons of party leadership like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., House Majority Whip James Clyburn, D-S.C., Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D, N.Y., and progressive icon Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., all of whom voted yes on the legislation.

The change in the willingness on the part of some Democrats to embrace efforts to reform the nation’s criminal justice system is the result of a confluence of technological, electoral and generational factors, experts say.

“One thing that's apparent is the ubiquity of video cameras. Cell phone cameras have been recording things that prior to the revolution in video recording and cell phones would have been just a 'he said, he said,' assuming that one of the persons is still alive to testify as to what happened,” Darrell Miller, a professor at the Duke University School of Law, told ABC News.

The overall decrease in violent crime, which has fallen 51% between 1993 and 2018 according to data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), has also likely lessened the worry for some Democrats in being labeled as “soft on crime” Miller said.

Lastly, the rise of a younger generation, more engaged on social issues and largely at the forefront of recent protests, has pushed Democrats, and Biden, to a place where embracing certain criminal justice reform policies is no longer seen as a significant political liability.

“The fact that people in the Millennial generation and Gen Z are really plugged in to social issues...has really changed the nature of the conversation about criminal justice reform and actually made it possible for Democrats to embrace reform without being frightened away, that their suggestions are going to be labeled as soft on crime as opposed to really wanting genuine, equitable reform of our criminal justice system,” Miller said.

“The socio-economic and criminal justice environment is different in 2020 than it was in 1994. Like a good politician, but also like a good policy thinker, [Biden] knows that when times change, policy needs to change.”

But while Biden may be shifting his own policy prescriptions, proponents of more fundamental reforms say he still must address his long record on criminal justice in a way that reflects a true understanding of the new political dynamics.

During a town hall with NAACP Wednesday night, Biden said that questions about his record, and involvement with the 1994 crime bill are “legitimate,” but a tense exchange surrounding the suggestion that Biden may struggle to win over young voters due to that record put a fine point on the concern.

”The vice president has to, at some point, address his own record. And he's going to have to address it with some new thinking in terms of remedies to what the largest criticism of him has been, which is the role that he played in the Crime Bill of '94. He has to address that, and leaning on folks who can help him to arrive at a set of policy solutions that correct the major problems of that ill, and also get us to a very different place in terms of police reform,” Adrianne Shropshire, the executive director of BlackPAC, a political organization that aims to boost black candidates seeking public office, told ABC News.

Biden’s campaign insists that the former vice president hears the concerns and shares the goal of addressing the systemic racism that exists within law enforcement.

“While they do not agree on all of the same strategies, Vice President Biden and these activists share the same goal: reduce incarceration - especially the fact that too many African American and Latino people are incarcerated - while also improving public safety,” Feldman said.