Inside Lesbos' Moria camp, home to thousands of trapped refugees and migrants

— LESBOS, GREECE -- In her temporary home, a fraction of a tent, Aziza Hommada holds up a transparent plastic bag with pita bread. The plastic has little holes in it and the bread is in pieces.

“Look,” she says. “The rats come into the tent and eat our bread. I have to throw this out.”

Hommada, 37, is five months pregnant and lives with her six children in the Moria camp, the largest refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos.

The words “Welcome to prison” are spray-painted at the entrance and barbed wire surrounds the camp, which used to be a detention center for rejected asylum seekers. Tents and containers are packed tightly together, with narrow, muddy passageways between them. Trash spills out of overflowing garbage bins and piles up on the ground. At night, bonfires light up the faces of children and adults who try to stay warm.

As Europe experienced an unprecedented influx of refugees and migrants in 2015, the camp was originally a temporary solution that could house up to 2,000 people. When ABC News visited the camp in mid-January, it was home to more than 5,300 people, according to the director of the camp.

ABC News was granted rare permission to access a small area of the Moria camp, and also visited other parts where journalists were not allowed.

Like most people in the camp, Hommada and her children share their living space. A piece of fabric splits Hommada’s tent in two. She lives with her children in one half while some of her relatives occupy the other.

She washes laundry by hand using water from a room right next to her tent. The floor there is brown from dirty water and on one recent evening two rats peeked out of a corner.

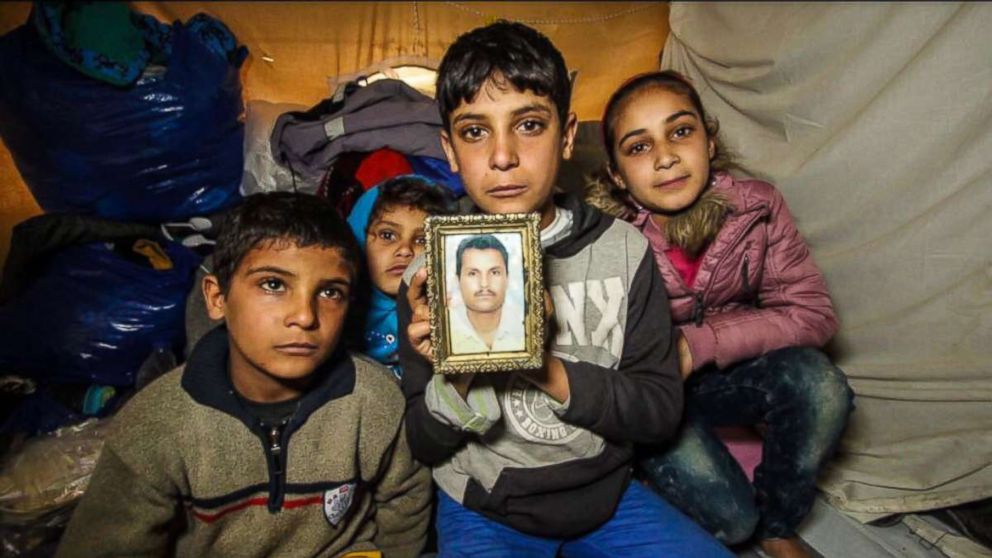

The family escaped from airstrikes and fighting between ISIS and the Syrian government in their village in Deir Ezzor, Syria. The family became separated when Hommada's husband left to pick up his sister from another village, she says. She has not heard from her husband or been able to find out what happened to him. She arrived in Lesbos with her children about two weeks ago. Even though the family is now safe from airstrikes, Hommada feels scared in the camp, especially at night.

“I don’t sleep from the fear,” says Hommada. “If anyone walks by our tent at night I sense it immediately and feel frightened.”

International organizations operating on the island say lack of security and hygiene are two major issues in the Moria camp. The UN warned earlier this month that women and children are at risk of sexual violence in the camp and called for more police. It described the bathrooms there as “no-go zones” for women and children after dark if they are not accompanied. Even showering during the day can be dangerous, the UN said.

In his office inside the Moria camp, Giannis Balpakakis, the camp's director, who is appointed by the Greek government to run it, lets out a sigh.

“The only problem is that there are a lot of people and it is difficult for us,” he says when asked why the camp is crowded and dirty. “If you have an apartment with one kitchen and two bedrooms and this apartment is for two people and in the same apartment you put 10 people you will have a problem. This is the problem.”

New containers were recently added in the camp, increasing the capacity from 2,000 to 3,000, he says, but it’s still not enough. People keep arriving to the island and the camp is crowded, he says -- so crowded that staff members clean the bathrooms and toilets only to find them dirty again one hour later.

“We may make mistakes, we may not be able to get to everything, but we are trying really hard,” he says. “All of us here are striving for the betterment of the people. I’m not saying that it’s the best, but we earnestly try. Everyone talks countless hours on the phone, to get everything in order, to strive, but I say to you honestly the problems that we have here are huge. Why? Because we constantly have new people. There is this stress, to welcome 100 people today, then 200 tomorrow, then another 100.”

In March 2016, the EU sealed a deal with Turkey intended to stop illegal migration to Europe by closing the main route that a million refugees and migrants had used to cross the sea to Greece. Since the EU-Turkey pact went into effect, the Greek islands have received a much smaller number of migrants and refugees. But in the second half of 2017, the numbers increased. Since September, more than 16,000 migrants and refugees have arrived on the Greek islands by sea from Turkey. And while asylum seekers before the EU-Turkey deal could move to the Greek mainland after typically just a few days on the islands, they now wait on the islands for months -- and in some cases, more than a year.

Under the agreement, which has been criticized by humanitarian organizations, refugees and migrants who manage to cross the sea to Greece are trapped on the islands. They face being returned to Turkey, unless the Greek authorities determine that they should be granted asylum in Greece. Only vulnerable asylum seekers such as pregnant women, unaccompanied children and torture victims -- or asylum seekers with close family members elsewhere in Europe -- are allowed to move to mainland Greece. But even those vulnerable people often have to wait on the islands for months for a decision.

The crowded conditions create tension and fights break out in the camp, Balpakakis says. There are also problems with the infrastructure and electricity. At one point during the interview the lights in the director’s office go off because of a sudden power outage.

Deeper inside the camp Jihad Al-Haj Hussein Al-Hilal, 50, lights a cigarette in his part of a shipping container that serves as a temporary home. When he lived in his Syrian hometown in Deir Ezzor under ISIS rule, smoking was not allowed. He escaped intense fighting between ISIS and the Syrian government there and has been on Lesbos with his family since late October.

“I’m still trapped on this island,” says al-Hilal. “We escaped from death and came to death -- from quick death to slow death.”

It’s around dinner time and people line up for food outside. Residents say they usually have to wait two to three hours for a meal. A sound of men yelling makes its way into the container.

“Can you hear that?” asks Jihad. “They’re fighting. It happens a lot when people line up for food.”

The conditions in the camp surprised him when he arrived, he says. “I had expected that I would at least feel safe here,” he says.

Berevan Ahmad Hassan, a 25-year-old Kurdish Syrian from Aleppo, fled her country after an airstrike destroyed her home and all her belongings. When she saw the wreckage, she actually felt relief. Her children and husband were safe and that was all that mattered to her, she says. But after seven years of war, she decided to leave her country for the safety of her 5-year-old and 3-year-old. In Greece, her children often wake up screaming at night because they see bombs in their dreams. They refuse to use the toilets in the camp unless their mother cleans them first.

“They have started bed-wetting,” she says. “They didn’t do that in Syria.”

She has lived with her family in a tent for two months. The conditions in the camp are far worse than she imagined, she says. Every morning when she wakes up her first thought is: I can’t wait for this day to be over.

“I think, I hope this day will go by fast so that it will be night so that I can reach the day when I will get out of here,” she says.

She wants to settle in an actual home where her children can feel like they are living a stable life. And she wants them to go to school.

“It will be a while before that can happen. We will suffer until then,” she says. “But after everything we’ve been through I can’t imagine that I will end up regretting coming. I can’t think that. I have to think that it will be good.”

After ABC News left the Greek island of Lesbos, the Hommada family told ABC News that they had been transferred from the Moria camp to Lesbos' Kara Tepe camp, which is known to have much better conditions than the Moria camp. The family said they now live in a container by themselves rather than a shared tent.