Inside the international manhunt for Martin Luther King Jr.'s killer

Thousands of FBI agents spent months hunting down every lead looking for Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassin, but the final crack in the case came almost by accident.

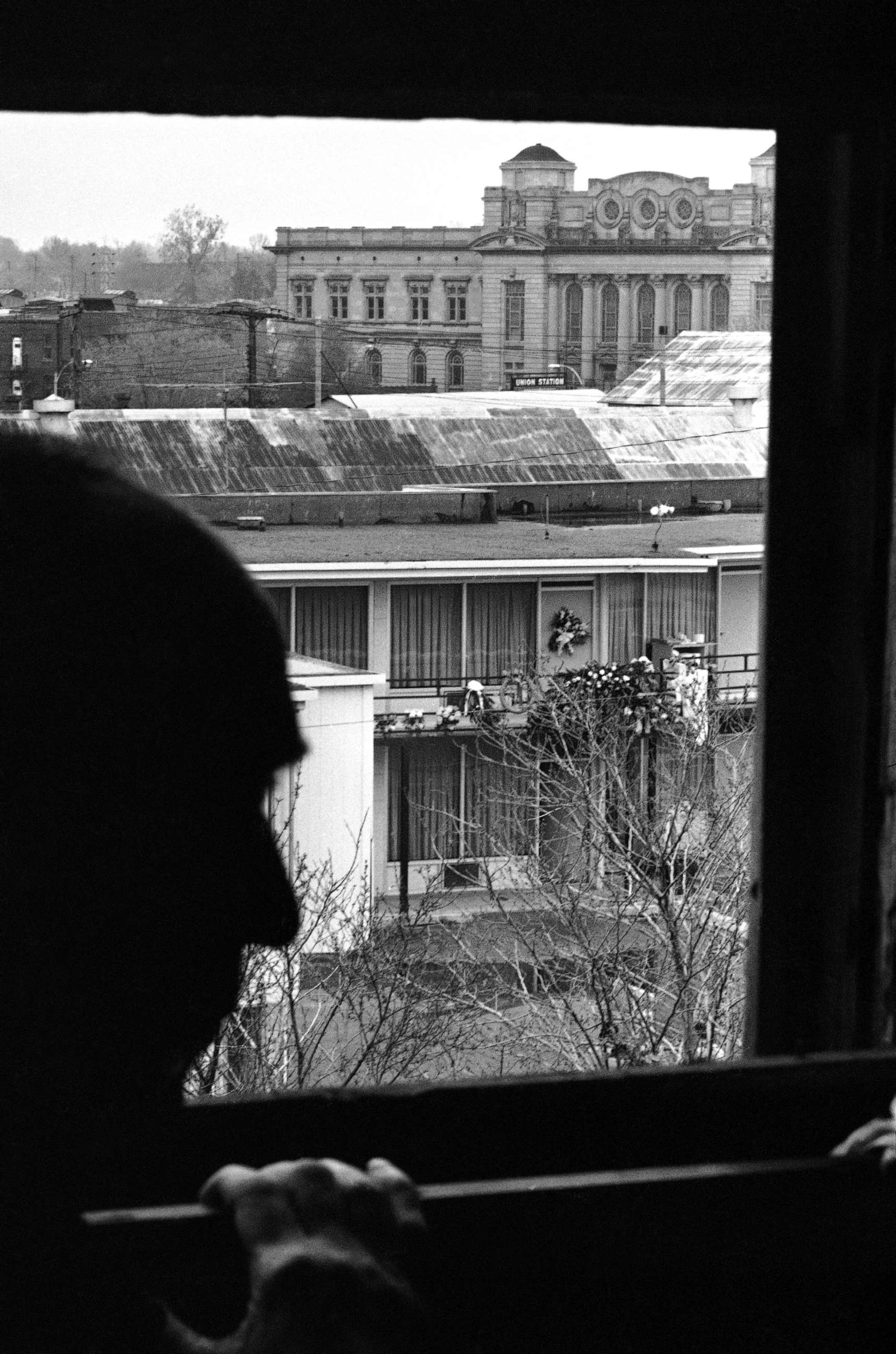

King was fatally shot 51 years ago today, on April 4, 1968, while standing on a motel balcony in Memphis. The massive manhunt for his killer, James Earl Ray, started shortly after he fired his rifle from the bathroom of a nearby boarding house.

As the FBI launched into what would turn into a two-month, international manhunt, the country started to burn.

Riots and unrest were reported in more than 100 cities following King's death, with the most damage reported in Baltimore, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. According to the Washington Business Journal, the nation's capital sustained $27 million in damages at the time, which equates to $193.4 million in 2018 dollars.

The urgency to catch King’s killer was real, and the now-50-year-old saga remains one of the biggest manhunts in U.S. history.

From examining thousands of fingerprints by hand to tracing down a new technique used by a small number of laundromats after a lead found in the seam of discarded underwear, agents worked through a seemingly endless stream of leads as the world waited for the killer to be caught.

“I would say it’s probably one of the largest criminal investigations in the history of the bureau, no question,” said Ray Batvinis, a former FBI agent who worked in the bureau at the time but was not directly assigned to the case.

The shooter

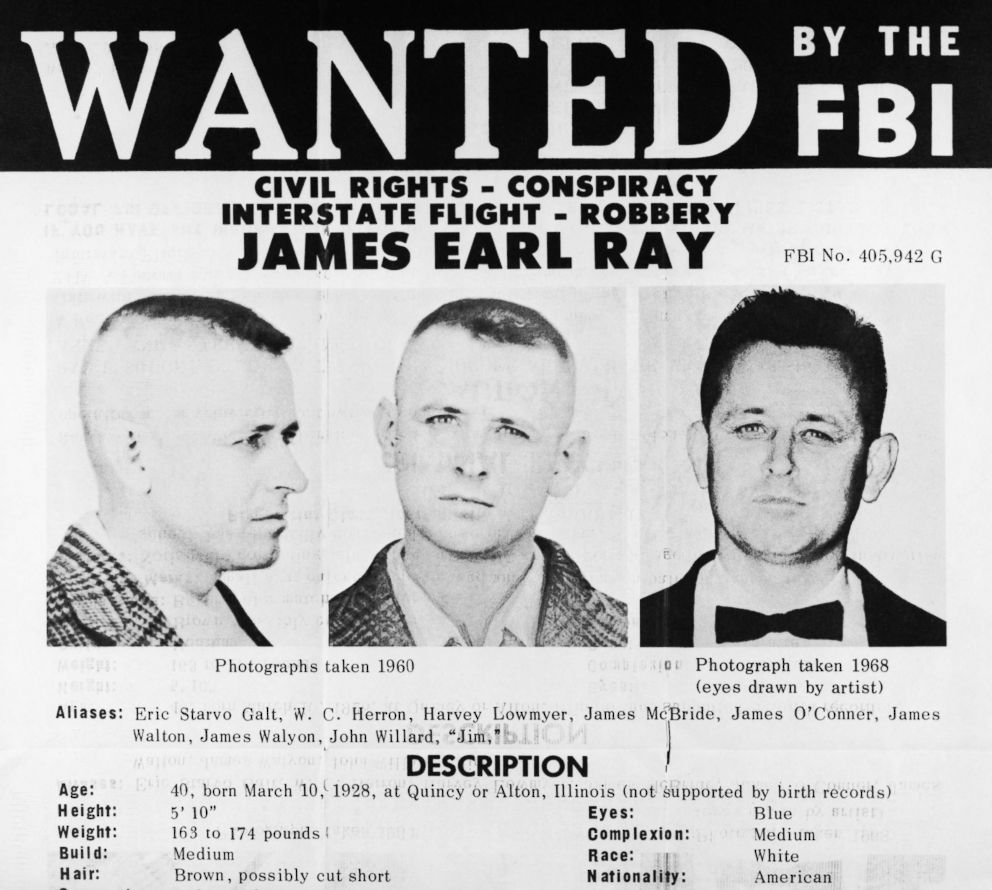

Though there have been decades of conspiracy theories surrounding King’s death, part of the trouble that came in the early stages of the investigation stemmed from the fact that there were a number of names associated with different parts of the crime.

One name was used to check into Bessie Brewer’s rooming house in Memphis, across the street from the Lorraine Motel, where King and his associates were staying.

Another name was used a week before the shooting to buy a rifle in Birmingham, Ala., which was later exchanged for the weapon used in the King shooting.

And then there was the name that authorities would eventually tie to both: James Earl Ray, the man ultimately identified to be the shooter.

Ray had accrued a criminal rap sheet that included burglary, armed robbery and mail fraud well before his path crossed with King. He escaped from a state prison in Missouri the year before King’s assassination by sneaking out of the premises in a bread truck.

“He used 17 different aliases over the course of his criminal career,” author Hampton Sides told ABC News.

Sides, who wrote the book “Hellhound On His Trail” about the manhunt, called Ray “a very mysterious and a really hard person to pin down.” He added that he doubts many know that Ray was “a convict who had escaped from a prison and who had traveled all over America.”

Endless leads

The ensuing search for King’s shooter started in Memphis but led across the country as investigators started tracking Ray’s prior movements, hoping to learn as much as possible about the man who killed the country’s best known civil rights leader.

Sides said that more than 3,000 agents investigated the case, following thousands of leads and thousands of anonymous tips, making it “the largest manhunt in American history up to that point.”

The intricacy of some of the leads that they followed shows how agents were grasping for any and all clues to find the killer.

One came in the form of an unusual number, stamped onto the shell of a transistor radio found in the room the shooter had rented.

Sides said investigators later determined it was the prison number Ray had been issued when he was in the Missouri State Penitentiary.

“He had bought this radio in the canteen and before they issued him the radio they stamped [the number on],” Sides said.

Another lead was the “almost microscopic number in the inseam” of a pair of undershorts found in the boarding house room.

The number ended up being a part of a new technique that certain laundromats had started using to identify customers.

“Armies of guys ended up in Los Angeles, scouring every laundromat in southern California,” Sides said.

One reason for the significant manpower stemmed from the fact that the search happened in the era before computers, meaning that every step had to be handled by hand.

When it came to running the fingerprints off the gun that was found tossed in the street near the site of the shooting, that meant there were “armies” of fingerprint analysts “just eyeballing and comparing them” to the fingerprints of “every known felon who was on the lamb or had escaped from any prison or skipped bail,” Sides said.

Eventually, one of the prints matched, finally connecting the shooter to the convict who had escaped from the Missouri State Penitentiary.

On his trail

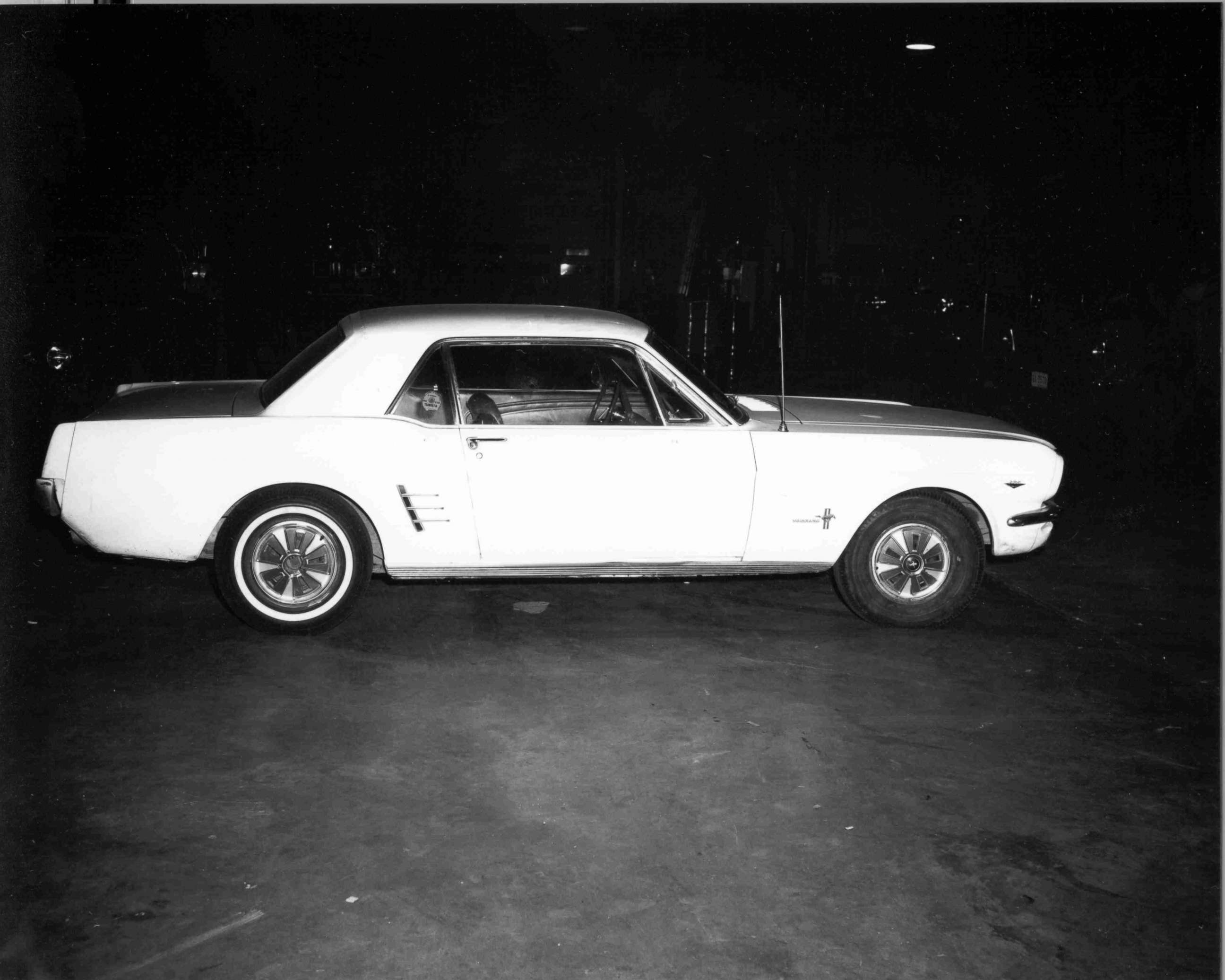

Ray got out of Memphis in his white Mustang, according to archives from the House investigation, and was headed at first toward New Orleans before changing direction after hearing radio reports about the police search for King’s killer.

“After his flight from the immediate scene, the evidence established, moreover, that he drove for 11 hours to Atlanta, Ga., where he abandoned his automobile, picked up laundry, hastily packed some belongings at Garner's rooming house, and then fled north to Canada,” the report in the National Archives states.

He rode a Greyhound bus to get from Atlanta to Detroit, and then a taxi to cross the border into Canada.

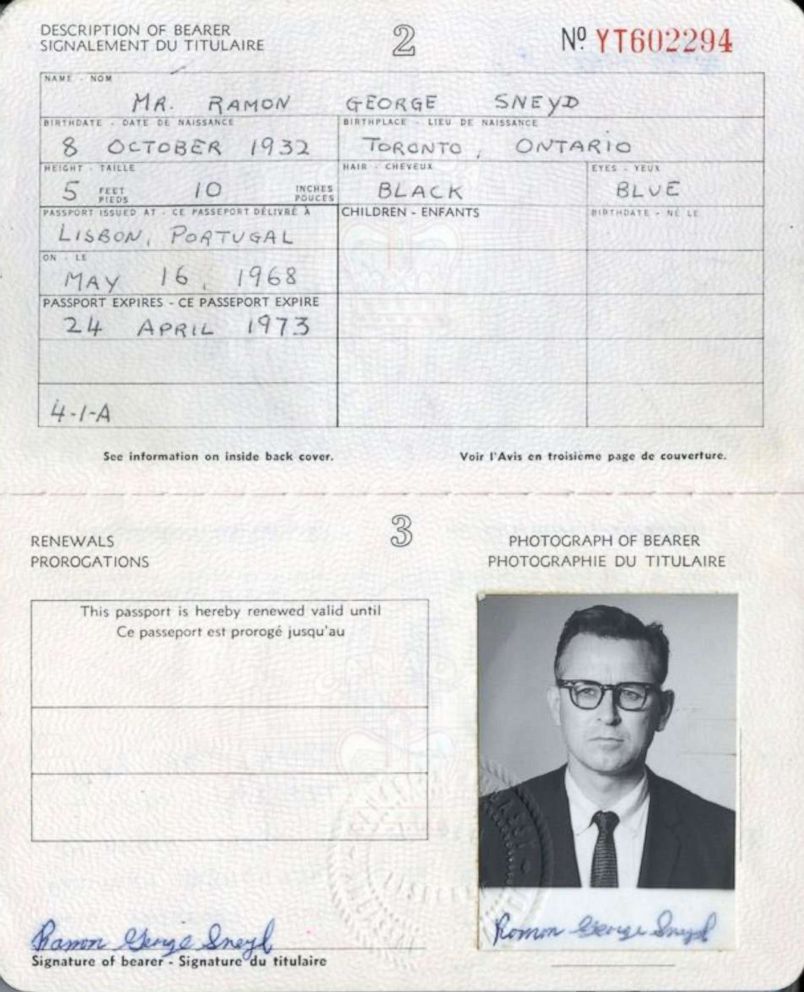

The pull toward the neighbors to the north was not only to evade American authorities but also because it had been a haven for him in the past where he had some contacts and was able to obtain false identification.

“It was very, very easy to get a passport in Canada at that time. It was an extremely trusting place,” Sides told ABC News.

Ray told investigators that he went to a public library in Canada and looked up birth announcements from the same year that he was born. From there, The Toronto Star reported that he took some of those names, looked up their current addresses, surveilled the homes and looked for physical similarities between him and the prospects.

The paper reported that he went on to call the individuals he thought looked similar enough to ask if they had recently filed for a passport.

That’s how Ray ended up using a Canadian passport under the name Ramon George Snyed, a picture of which is included in the James Earl Ray exhibit at the Shelby County Register of Deeds.

From Canada, Ray went to London, though Sides said there were indications he planned to move on from there. Sides said it was “hard to really know what [Ray] was ever doing because he lied so much. But it was very clear that he was trying to get to South Africa or Rhodesia.”

Rhodesia, which was the former name of the country that is now Zimbabwe, would have likely been an attractive destination because they did not have an extradition policy with the U.S. and, Sides said, it “doesn’t hurt that it was a white supremacist state.”

After arriving in London on May 6, Ray went to Lisbon, Portugal, the following day, which many believe was an effort to make his way toward Africa. After reportedly missing a boat toward his ultimate destination, he returned to England and struggled to figure out his next steps.

In the following weeks, he tried and failed to rob a jewelry store, and then robbed a local bank but didn't make off with much.

The moment he was caught

On June 8, 1968, it had been more than two months after King was killed when a customs officer in London’s Heathrow Airport spotted a customer who had two Canadian passports as he tried to check in for a flight headed for Belgium.

“The officer who detained him had no idea he was James Earl Ray,” Sides said.

Ray was at the airport attempting to buy a ticket to Brussels when the customs officer saw he had a second Canadian passport and asked him about it.

Sides said both passports were under the name Ramon George Snyed, but one had a typo, prompting the customs officer to look into it. He found the name on the printed "watch and detain" list, and so he did just that.

British police from Scotland Yard interrogated Ray and that’s when his true identity was realized.

Bill Baker was an FBI agent in northern Florida at the time of the case and he worked at the bureau for 26 years before retiring as the assistant director in the criminal investigative division. He recalled how “we were all relieved” after hearing about Ray’s capture.

Then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover “sent one of the largest guys we have in the FBI to go pick him up from the British police and bring him back to this country,” he said.

The tense personal history that existed between Hoover and King before the civil rights leader's death reportedly played a role in the scrutiny that the FBI was under during the course of the manhunt.

“The FBI had done everything it could possibly do to smear Martin Luther King and ruin this [civil rights] movement, but once this manhunt got started, you began to see the FBI doing its job,” Sides said.