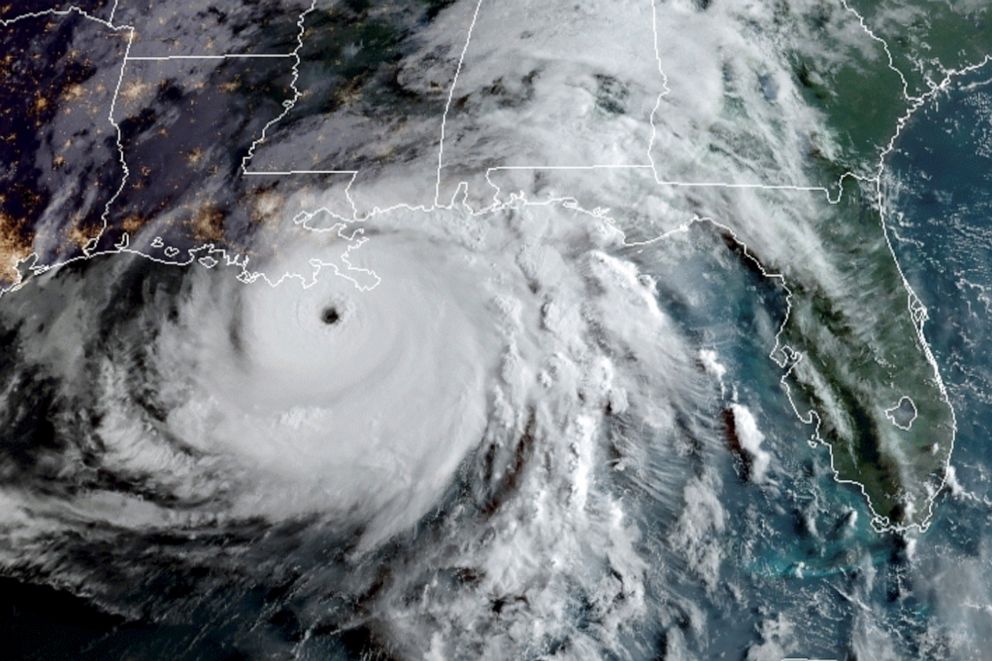

Hurricane Ida aftermath: Here's how climate change is making hurricanes more devastating

Hurricane Ida is the kind of natural disaster that brings terror to people who have lived through deadly storms.

Seeing Ida's maximum sustained winds topping 150 mph, torrential rainfall that overflows waterways and makes roadways impassable and storm surge so powerful it could destroy entire communities, it is difficult to face the reality that these types of events will become more commonplace in the future, as the planet continues to warm.

"It's really been a devastating summer in terms of the impacts that we've seen across the Northern Hemisphere this this year," Jason Smerdon, a climate scientist for Columbia University's Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, told ABC News. "So this is just one more piece of bad news and lots of events that are impacted by global warming."

While the overall number of hurricanes is not likely to increase as a consequence of global warming, researchers believe that over time, the storms that generate will get stronger and more intense.

There are several "rock-solid ways" global warming is already impacting hurricanes, Smerdon said, and the evidence is in the numbers.

The year 2020 was a record-breaking year, with 30 named storms -- the most in history -- and double the normal number of storms designated as hurricanes.

Over the last three years, hurricanes have tended to intensify more rapidly, which could be due to the warmer water available, Philip Klotzbach, a research scientist at Colorado State University's Department of Atmospheric Science, told ABC News before the 2021 hurricane season began.

Four of the eight fastest intensifying storms occurred in the past five years. Hurricanes Ida and Laura -- both on that list -- are two of the three strongest hurricanes to ever hit Louisiana, and they took place just one year apart.

"The people that live on the Gulf Coast of the United States can expect more of this type of thing, because climate change is heating up as we speak," William Ripple, climate scientist and professor of ecology at Oregon State University, told ABC News.

This is how hurricanes will become more powerful and destructive as the climate continues to warm:

Warming sea temperatures allow the systems to intensify

Hurricanes garner their energy from warm sea surface temperatures, over which they develop and move. So, because global warming increases sea surface temperatures, it increases the capacity for larger, more intense storms to develop, since that additional energy is available, Smerdon said.

As Ida approached landfall Sunday afternoon, it churned over some of the warmest waters in the Gulf of Mexico -- up to 3 and 4 degrees Fahrenheit higher than normal, in some areas. That likely contributed to the rapid intensification of the hurricane in the 24 hours before it hit land, at which point it reached maximum sustained winds of up to 150 mph.

But it's not just the surface water that's gotten warmer due to climate change, the deeper water has too.

Typically, the water underneath the surface is cooler, so when strong winds from a storm stir it up with the warm water at the surface, the cool water helps bring the intensity of the storm systems down, Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished scholar at the National Center of Atmospheric Research, told ABC News.

While the temperatures for August are not yet available, July was "exceptionally warm" at 50 meters below the surface, Trenberth said, adding that the buildup of heat has a "substantial climate change component."

"With exceptionally warm subsurface waters, the hurricane is instead continually fueled and leads to more activity," Trenberth said.

More moisture in the atmosphere leads to more rainfall

The warming planet has allowed more moisture to be held in the atmosphere, allowing monster storms the capacity to accumulate and precipitate that moisture when they fall onto land, Smerdon said.

"More moisture in the atmosphere means more moisture in the hurricanes, which means more moisture that they ultimately dump out when they make landfall," Smerdon said.

Ida drenched portions of Louisiana in more than 13 inches of rain and continued onto other regions, such as Waverly, Tennessee, as the system slowed and weakened.

On Wednesday, the remnants of Ida were forecast to bring severe storms and heavy rain to Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia and southern New Jersey, more than three days after it made landfall in Louisiana.

That kind of longevity in precipitation that resulted from Ida will unfortunately become "more commonplace," Smerdon said, noting that in 2017, Hurricane Harvey dumped 2 to 4 feet of rain in the Houston metropolitan area over several days.

"We've seen it elsewhere, from flooding in Europe this summer and Waverly, Tennessee, last week, because of the increased moisture in the atmosphere," Smerdon said.

Rising sea levels are making storm surge more destructive

As ice sheets and glaciers accelerate their melting, sea levels continue rising rapidly, which also boosts hurricanes' destructive capacity.

Storms are now operating on sea levels higher than they were 100 years ago, Smerdon said. This puts coastal communities -- built for the sea level of some years ago -- more at risk.

"Now we're getting storm surges that are more damaging," Ripple said.

Officials and communities need to be prepared

Every country will need to undergo climate adaptation as natural disasters of all kinds intensify in proportion to rising global temperatures.

"Both government officials and residents in hurricane-prone zones will need to heed a higher level of preparation as Earth moves from the early stages of significant climate change," Ripple said.

In addition, large-scale mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions will be needed to curb climate change and all of the ramifications that come with it, Ripple added.

"So we need to encourage our policymakers and plead with them to do more to curb future climate change, to help mitigate climate change, to try to put a lid on it," he said. "...Things could get much worse than they are right now."

ABC News' Melissa Griffin contributed to this report.