High school students draft bill to uncover decades-old civil rights cold case records

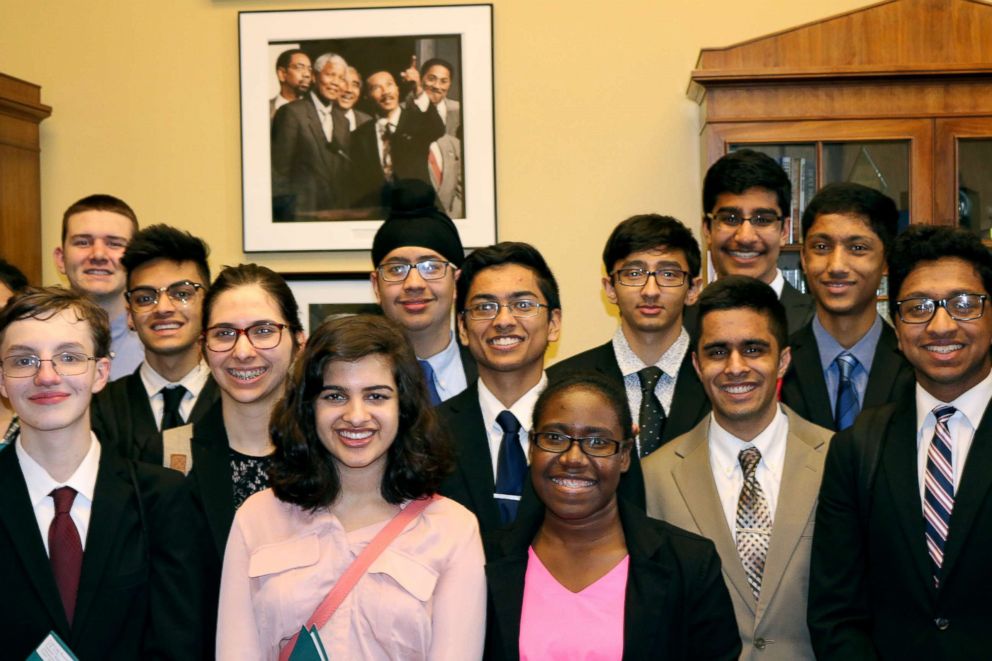

New Jersey high school students made history earlier this year by becoming the first known high school class to draft a bill, lobby it in Congress and eventually have it signed into law.

It all started three years ago in an honors civics class at Hightstown High School. Stuart Wexler was teaching his students about the Civil Rights movement and specifically about the various racist hate crimes taking place at the time that went unsolved. After some research, the class discovered that around a dozen of these cases had recently been reopened and then closed again without resolution.

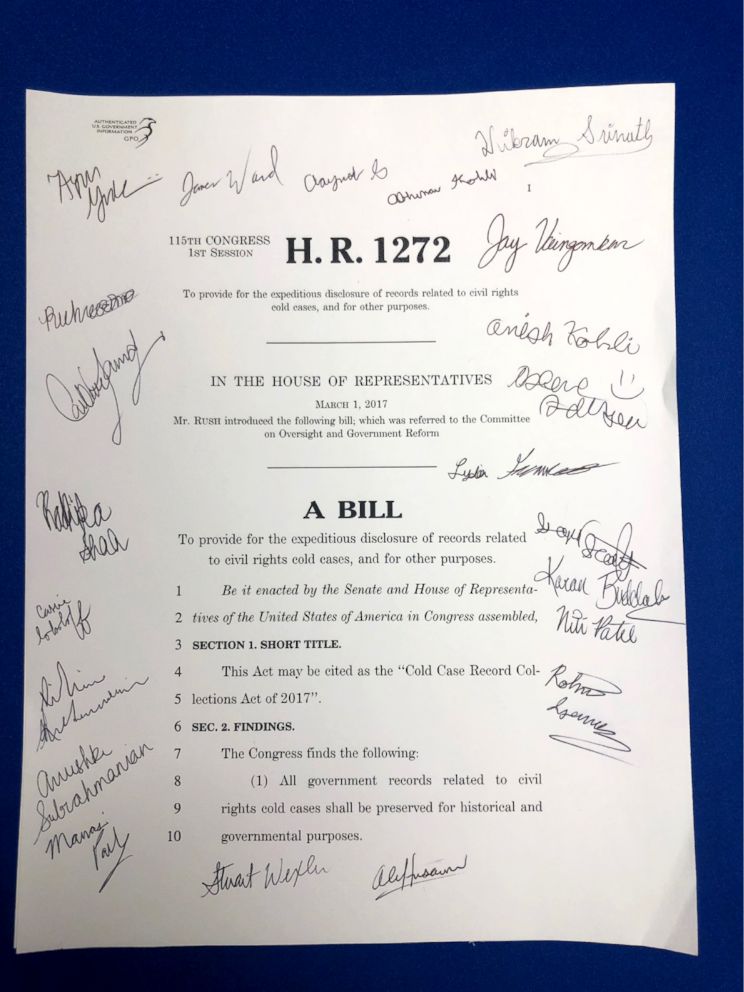

Oslene Johnson was a junior in high school at the time and said that the class was then motivated to try and provide some sort of justice for these victims and their families. They decided to create a shared document where they worked together to draft what is now the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Collection Act. The law requires that decades-old government records relating to unsolved civil rights cases be reviewed, declassified and released to the public.

"I think the most important driving force for us throughout this entire process has been what it could possibly mean for the families of the victims able to have access to the information about their relatives about what happened to their relatives," Johnson said.

The students spent the first year drafting the bill, but then came the tricky part: getting members of Congress to sign on to the bill. Students would spend their class time making phone calls, sending emails and tweeting to Congressman trying to get their bill some type of attention. Some even traveled to Washington, D.C. and lobbied their bill to congressman on their own.

Aditya Shah was also a junior in the civics class and said that it was difficult at first getting congressman to take their efforts seriously and that they received a lot of rejection initially. However, once the students were able to get in the door and get a meeting, Shah said they always made an impression.

"I remember one of the staffers telling me, 'Wow you guys are way more prepared than some of the actual lobbyists who come in and lobby for their bills,'" Shah said.

Illinois Rep. Bobby Rush was the first congressman to sign on as a co-sponsor of the bill and said that he was overwhelmed and inspired by these students' dedication and persistence.

"They came up with a great solution to an unrecognized and unacknowledged problem that existed for years," Rush said.

Alabama Sen. Doug Jones was also one of the early supporters of the bill and introduced the bill to the United States Senate. Jones said that he was also impressed by how much research the students did on the issue of these civil rights cold cases.

"They really understood how important it was to bring some healing to these communities," Jones said.

Some of the students actually traveled to Washington, D.C. to witness Sen. Jones introduce the bill on the Senate floor, and said it was a day they will never forget. Some sitting in the Senate gallery had to fight back tears as they watched Jones give an impassioned speech about their bill and its' importance.

Three years later, the bill was signed by President Trump and for students like Shah it is still a little unbelievable.

"We were able to surmount each challenge and we grew in our passion and our vigor and I just was so proud to see that all of our efforts, determination, hard work and drive was able to help so many people's lives and change the dialogue in a nation," Shah said.

The law requires the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to create a collection of records for unsolved criminal civil rights cases that all government offices must disclose to without redaction. It also establishes a Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board which will operate as an independent agency made up of private citizens that will be responsible for reviewing the records and the public disclosure of the records relating to such cases.

Rush, who has a long history with the civil rights movement in Illinois, said he hopes the release of these records will help solve civil rights cases that nobody cared about and provide investigative facts for families.

"There will be no guessing, no speculating," Rush said. "So in some instances families will be relieved, and in some instances they will be grieved. But they will know what the facts are."

For the students, one of their major takeaways was that it showed them what it means to work together as a country to implement change.

"What this has taught me is that, no matter my age, I can do something that can have a positive change that will affect our entire country," said Johnson.