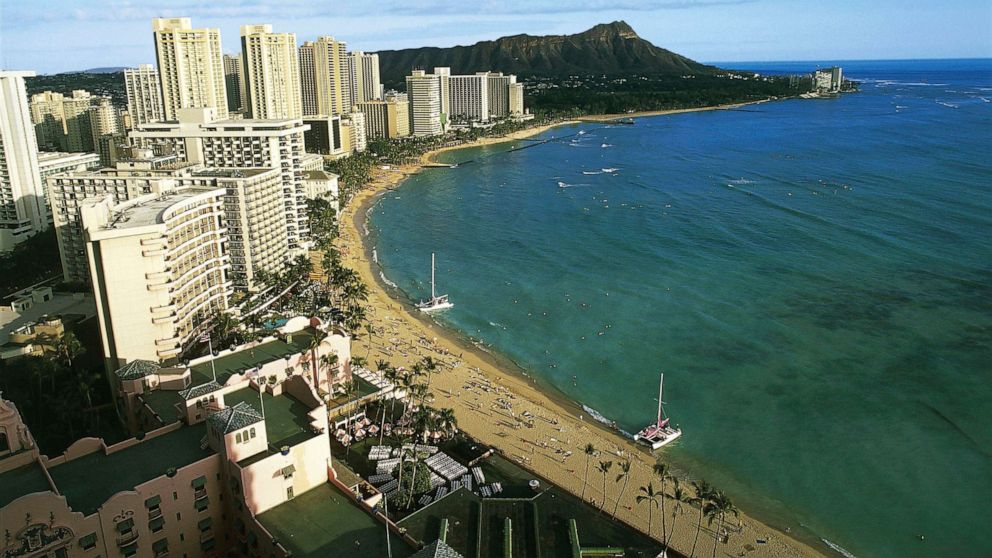

Hawaii's beaches are disappearing due to climate change

Rising sea levels paired with recent storm surges have been causing faster than usual erosion on Hawaii’s beaches and shorelines.

"The coastal issues that are related to climate change are sort of the canary in the coal mine," coastal hazards specialist Tara Owens told This Week co-anchor Martha Raddatz, who reported from Hawaii as part of ABC News' 'Climate Crisis: Saving Tomorrow' series. "Everybody who lives here in Hawaii is an oceanographer. ... You're looking at the tides ... you're paying attention to the waves. You can't ignore or bury the problems, because you see them every day."

According to a recent ProPublica report, three of Hawaii's major islands have lost roughly one-quarter of their beaches. Sea levels are also rising about one inch every four years, threatening 70% of Hawaii’s coastline, according to Hawaii’s state website.

Owens said that in Maui alone, 85% of shorelines are eroding and beaches are "narrowing" as a result.

"Here in Hawaii ... our community is very aware and engaged, and I think that's something we have to share with the rest of the country that might not get to see what we see," Owens continued.

In response to the U.N.'s recent "Code Red for Humanity" report -- and a possible "$3 billion loss in assets over the next few years," according to Maui Mayor Mike Victorino -- Hawaii became the first state to declare a climate emergency.

"Unless we take action today, we will lose all the beauty, many of our beaches throughout not only this state, throughout the world," Victorino told Raddatz.

Victorino has accused fossil fuel companies of playing a major part in the climate change effects Maui has been experiencing. According to a study conducted by the Hawaii State Energy Office, the state is expecting to pay "at least $19,000,000,000 in losses from sea level rise alone."

"The fossil fuel industry has not been forthright with the people of the world, an island nation just like us, all island states like us, and island nations are the ones that suffer the most, most quickly," the mayor said.

Victorino has filed a lawsuit on behalf of the county to hold some companies responsible. Other states and municipalities have also filed upward of 26 lawsuits.

The rising tide is also jeopardizing condos, homes and hotels -- including the home of Filemon Sadang, a fisherman who was born and raised on the island of Maui.

Once, "[the] ocean was far out to sea, about 150 feet," Sadang said, adding that the shoreline has since receded tremendously.

Sadang blamed the rising tide on climate change. "We are in fear of losing our place, everybody fears losing our place. We have to do something now."

Seawalls and sandbags have been used as temporary fixes to protect properties and coastlines. However, they’re having adverse effects. After years of use, they've exponentially sped up the erosion of beaches by ripping up the seafloor and preventing natural sand replenishment.

In an effort to prevent further damage, local Hawaii officials implemented a no tolerance policy toward new seawalls back in 1999.

Private property owners, however, were able to get around the policy by filing for an exemption. The state has since provided upward of 230, according to a Honolulu Star-Advertiser and ProPublica report.

"We're really suffering erosion because of sea level rise, which is secondary to global warming," said John Seebart, a representative for threatened beachfront condo buildings in west Maui. "So that's the big deal," he told Raddatz.

"When you look at this building, how endangered do you think it is of disappearing if measures aren't taken?" Raddatz asked.

"I'm not an engineer, but ... if we had a huge storm, it could go this season," Seebart warned.

Seebart pointed out flooding basements, water in parking lots and sinkholes reaching "12 to 15 feet" in depth.

His team has been working on long-term fixes such as jetties -- a long and narrow structure that can be used to protect the coastline from erosion. According to Seebart, smaller T-shaped jetties, which he referred to as "groins," are being put in to fix the erosion problem that was worsened by the sandbags.

Seebart said the jetties will simultaneously hold and "recirculate" the sand to create a more "natural beach."

In addition to homes and other buildings, roads are also at risk.

Victorino mentioned the threat to Maui’s roadways, saying that waves run over the roads because of high sea level rise and tidal action.

"It's really hurting us as a community, because it's now cutting us off at times," he said.

That includes roads like Honoapiilani Highway, a major roadway that connects the west side of Maui to the rest of the island. Lauren Blickley, regional manager of Surfrider Foundation, an environmental organization, said over 20,000 people live on the other side of the highway and rely on it as their only point of access to the hospital and center of town.

"This highway has been built too close, and we literally at this point have waves that are washing up and undermining the road," Blickley said while standing next to the highway as waves nearly washed over her feet.

"To permanently solve the issue that we're dealing with ... we have to move away from the ocean. The ocean is always going to win. Whether it wins this year or in 10 years or in 20 years is the question," Blickley said.

The U.N. reported that the surge in rising sea levels that’s driving populations inland and the ocean’s uptick in temperature can be blamed on the increase in global temperature. The report also stated that the Earth is dangerously close to reaching a global warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

According to the U.N.'s report, if the Earth reaches 2 degrees Celsius of warming, populations will experience heat extremes that “would more often reach critical tolerance thresholds.” The report states that these extremes will likely affect natural water production, agriculture and overall health.

The effects of rising ocean temperatures will inevitably trickle down into the food chain. According to Stefanie Sekich-Quinn, coastal preservation manager for the Surfrider Foundation, there will be a "chain reaction" if coral reefs aren't protected.

"If we don't have corals feeding fish, then fish aren't going to be able to sustain our diets," Sekich-Quinn said. "Coral and other components help absorb wave energy. So, when we start to lose our corals, we're going to have more intense storms, potentially more sea level rise."

Warming waters may also cause coral bleaching to occur. "Essentially, the algae that live within the coral get too hot, and they expel themselves," Sekich-Quinn said.

According to a U.N. Climate Report release in early August, scientists predict that 90% of the coral reefs will die off by the year 2050.

"Here in Hawaii, we have these traditional principles that really are the foundation of life here. And one of those is Malama 'Aina. [It] means to protect her, to care for our land," Blickley said. "We, wherever we are, we have a level of responsibility to protect the oceans, to protect our ways, to protect our beaches and to protect what we have."

ABC News' monthlong 'Climate Crisis: Saving Tomorrow' series features an in-depth look at the causes and risks of climate change and necessary steps to avoid further consequences.