Gun violence killed her daughter. How Chicago mom is rallying other 'warrior moms' for change

When Nyisha Beemon’s 18-year-old daughter, Jaya Beemon, was shot and killed in a shooting at a convenience store in February 2020 -- one of five innocent bystanders hit by a hail of 22 bullets -- Beemon made it her goal to bring awareness to the gun violence epidemic on the South Side of Chicago.

“We are living in a war zone in Chicago,” Beemon told “Good Morning America.” “They’re killing our kids.”

Chicago has long been synonymous with urban gun violence and so far this year alone has logged more than 3,000 shootings, according to statistics released Monday by the Chicago Police Department.

That’s more than double the 1,300 shootings this year in New York City, a city with nearly three times Chicago's population.

Despite some limited successes in recent attempts to address the issue and an overall reduction in crime, shootings and homicides continue to rise, police data shows.

Jaya was studying to become a nurse like her mother before she was murdered, Beemon said.

“She was just becoming into Jaya,” Beemon said. “Jaya had a heart of gold, she had empathy, she cared about people.”

Now, Beemon has dedicated herself to helping other moms who have suffered loss.

“A mother should not have to bury their child,” she said.

Watch ABC News Live on Mondays at 3 p.m. to hear more about gun violence from experts during roundtable discussions.

'An out-of-body experience'

Nyisha Beemon wishes she could go back to the morning of Feb. 25, 2020 and stop time.

The 36-year-old nurse and mother of four said that Jaya, her eldest daughter, met her at the school where she was teaching a Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA) class, but left to spend the day at the aquarium with her boyfriend instead.

On the way back from the aquarium, the couple stopped at a convenience store. According to Chicago police, three men approached the store and began firing into the market from the outside, shooting Jaya and four others.

She suffered a gunshot wound to the neck and was taken to University of Chicago Hospital, where she was pronounced dead.

At the hospital, Beemon said she broke down when she saw her daughter's body in a hallway.

“I was in a state of shock. It was like I had an out-of-body experience,” Beemon said. “Like outside my body watching this happen to somebody.”

Beemon said that her grief was intensified when she was dragged out of the hospital by police officers whom she said failed to give her space to grieve.

“Most moms, you know, hold their kid’s hands while they are still warm. I just passed out, I blacked out, next thing I know I’m being dragged out of the hospital on my hands and knees,” she said. “I’ve been a hospice nurse for years. I do not -- I cannot tell you the appropriate way for one person to grieve, and I can’t say how you gonna react or not… But I know that is inhumane.”

Arrest records show that Beemon was arrested for battery and resisting a police officer. Those charges were later dropped by Cook County State Attorney Kim Foxx, but Beemon said she is still haunted by the trauma she felt that day.

“I was dragged out of there like an animal,” Beemon said. “My daughter’s dead, and I’m in a jail cell.”

The Chicago Police Department did not respond for ABC News' request for comment.

Gun violence ravaging communities

In December, nearly one year after Jaya was shot and killed, a 15-year-old boy who was allegedly among the three shooters, was arrested and charged.

Two other suspected shooters remain at large, according to police.

Reflecting on her daughter's murder, Beemon says gun violence has plagued her community.

“We don’t have no value for life here in Chicago,” said Beemon, “This is urban terrorism.”

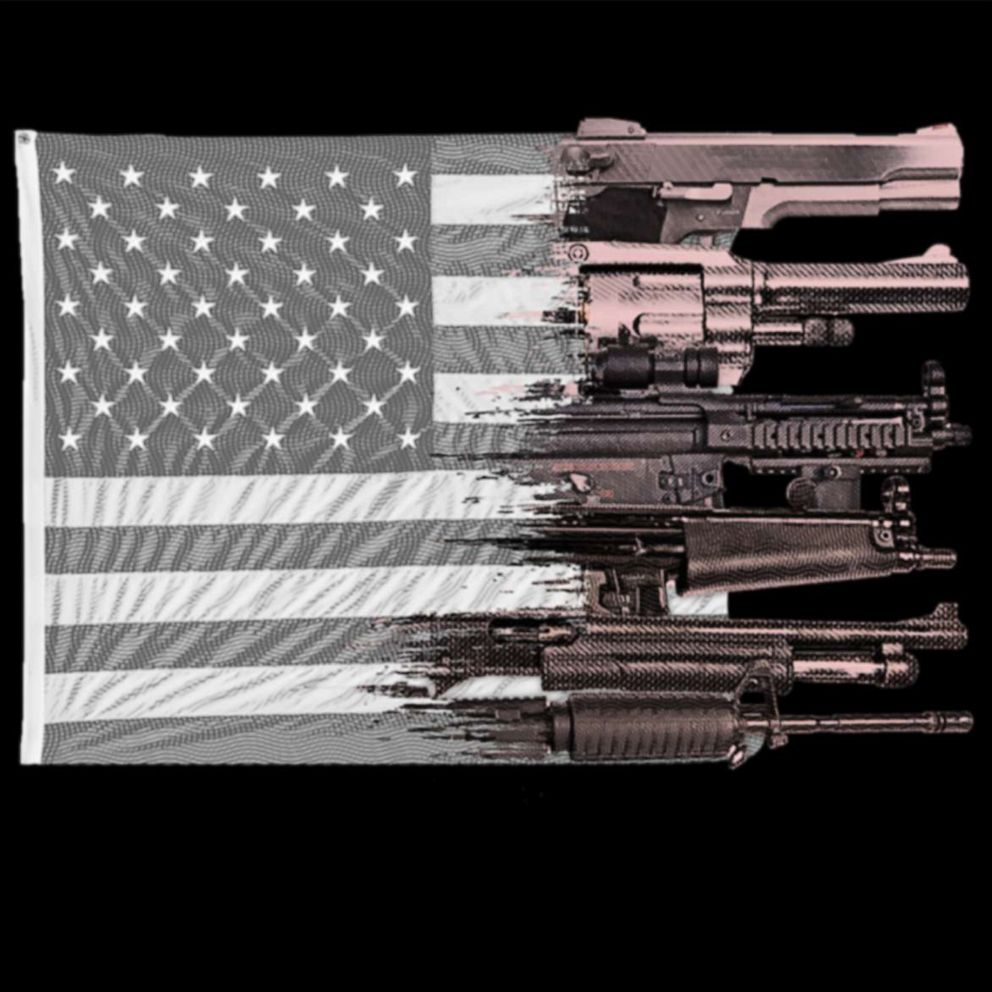

While cities and towns across the United States are facing an epidemic of gun violence, Chicago stands out. It became the focus of a pitched political battle over safety in cities during the Trump administration and despite numerous efforts to curb gun violence, shootings and homicides are both on the rise.

In 2021 so far, more than 3,690 people have been shot in Chicago, at least 300 more shooting victims than last year at this time, according to the Chicago Police Department's most recent crime statistics.

On the local level, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot last year unveiled the "Our City, Our Safety" plan, which aims to provide resources such as violence intervention programs, housing and job assistance to 15 of the most violent community areas.

The city's latest crime statistics show a reduction in homicides in one of the 15 most violent areas in the mayor's plan, as well as a record number of guns seized and an increase in arrests made in homicide cases, according to Chicago Police Superintendent David Brown.

"The emotional pain that victims and families of gun violence feel will never fully heal, but we can at the very least bring a measure of closure to those who have been hurt by these senseless actions," Brown said in a news conference Monday. "We are continuing to work with the community to bring those responsible for this violence to justice."

On the state level, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker on Monday declared gun violence a public health crisis at a news conference held in Chicago, pledging $250 million over the next three years to reduce gun violence.

Still, Beemon said she feels unsafe in her neighborhood, the South Side of Chicago, where the murder rate is 6.6 times higher than in North Chicago, a more affluent neighborhood, according to an analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau and Chicago Police Department.

“It’s the tale of two cities,” she said. “The South Side and the west side is one city, but then a nice up north and downtown is another city that everyday tourists come to.”

Beemon continued, “My home is on the south side of Chicago and I don’t feel protected.”

Rallying with other 'Warrior Moms'

In the days and weeks after her daughter's death, Nyisha Beemon said she was paralyzed by grief and scarred by how she was treated at the hospital.

“I was in a really dark place… I didn’t want to eat,” Beemon said. “I had support, I had friends, but I didn’t want to be a burden on nobody. It was just trying to figure out how I can deal with it.”

In a support group, Beemon said the grief counselor kept telling Beemon and other attendees to turn to God, but at the time, she had "no faith."

It was at this support group that she met other women whose children had also been killed due to gun violence and shared a painful bond. Together, they created an informal group and called themselves the Warrior Moms of Chicago to help one another and other mothers who have lost their kids to gun violence grieve.

“These are moms who’ve lost their kids to gun violence,” Beemon said. “We all know what each other has been through, everybody grieves differently but we understand.”

Like Beemon, the mothers in the group agree that the city has to do more to protect its residents from gun violence. As a group, they’re trying to put a national spotlight on what’s happening in their community.

“We are constantly living in fear,” Beemon said. “We cannot let our kids go outside to play."

“We need help in Chicago,” Beemon said. “We have programs, we have stuff here but it’s not getting it totally done. I think we need outside help from the National Guard or something because we are constantly living in fear.”

Keeping Jaya’s memory alive

Without her daughter, Nyisha Beemon has been determined to keep Jaya’s memory alive.

She teamed up with her cousin, Janice, to start a foundation, the Jaya Beemon Foundation, in her daughter’s name.

The foundation has created a scholarship fund for nursing students at Malcolm X Nursing College System where Jaya was studying to become a nurse like her mother when she died. So far, three people have received scholarships, according to the college.

“I just had to put my energy into the foundation,” Beemon said.

The Jaya Beemon Foundation also organizes events and programs to spread awareness about gun violence in Chicago. Beemon plans to continue to work with fellow "warrior moms" to make sure this doesn't happen to other families.

“Every time I hear of another kid getting killed, it takes me back to a dark place. I have to get myself up or figure it out because this is another mom feeling this hurt,” Beemon said.

“My daughter could be your daughter, your niece, your granddaughter, your cousin,” she added. “I don’t need your sympathy. I don’t need you to feel sorry for me. I just need you to have empathy. Put yourself in my shoes. What would you do? What would you want done?”