Gun violence in America: Mental health

The National Alliance on Mental Illness says whenever a tragic act of gun violence occurs, people with mental illness are often unfairly drawn into the conversation.

But experts say the relationship between mental health and gun violence is complex.

"Someone who goes out and massacres a bunch of strangers, that’s not the act of a healthy mind. There’s something wrong with that person," Dr. Jeffrey Swanson, professor in Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke University’s School of Medicine told ABC News. "But it doesn’t necessarily mean that they have one of these disorders of thought or mood regulation that psychiatrists commonly treat."

Swanson, who co-authored the study "Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: bringing epidemiologic research to policy," said the issue is complicated because there's rarely just one explanation for mass shooters; they could also be grappling with trauma, drug use, alcohol abuse, alienation or mental illness.

"When we think about gun violence, what we know is that extreme anger, hatred and violence can motivate people to hurt or kill others. But we should never confuse strong emotions and beliefs with mental illness," Angela Kimball, national director of advocacy and public policy for NAMI, told ABC News.

Because politicians, police and the public put so much attention on mental health in the wake of gun violence, Kimball said those who have been diagnosed with things like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder face discrimination and marginalization. She said the world will often confuse those conditions with things like psychosis, which has many causes, including paranoia, Alzheimer's disease, drug use, trauma or sleep deprivation.

According to Kimball, people with mental health conditions are 23 times more likely to be the victims of violence than the general public.

"Blaming mental illness or mental health conditions for gun violence is really a distraction from the real issues at hand which are evidence-based risk factors and the fact that in our country, it’s easier to get a gun than to get mental health care," Kimball said.

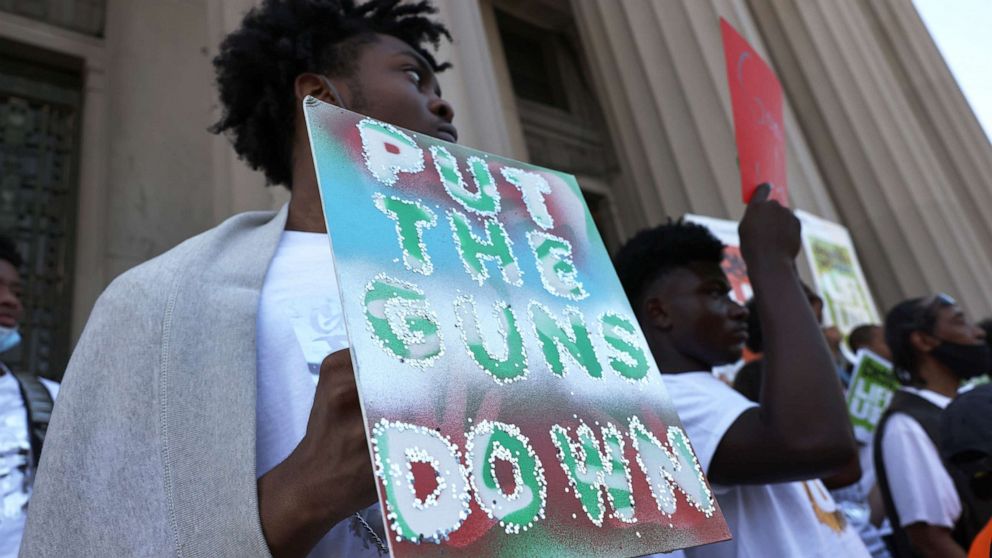

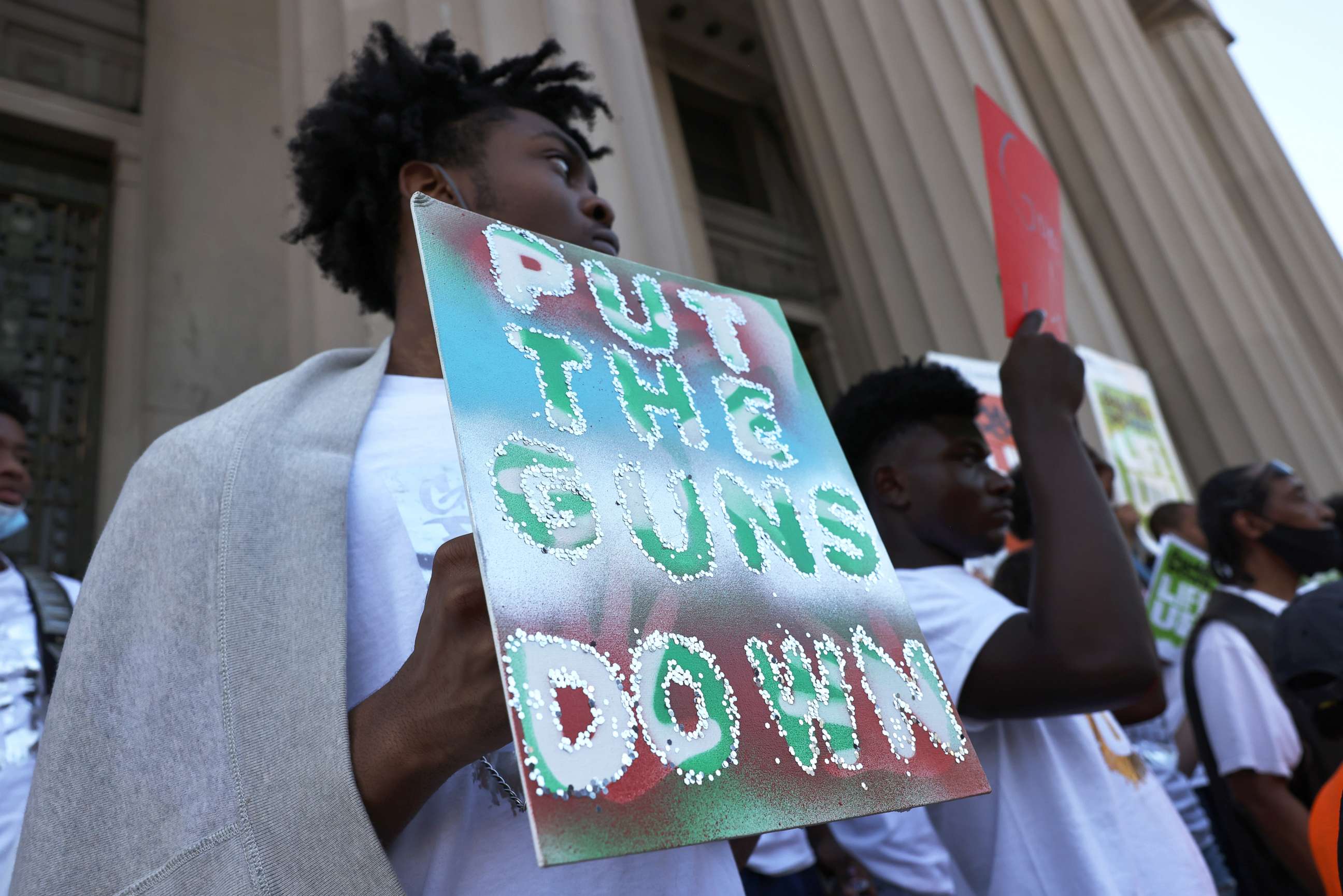

Access to mental health care has been a passion of Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart, whose county seat is Chicago, a city no stranger to gun violence. In 2020, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot released a three-year violence reduction plan that addresses what she calls the root causes of violence, including systemic racism, disinvestment and poverty. The Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office confirmed 875 gun-related homicides in 2020, breaking the previous record of 838 set in 1994.

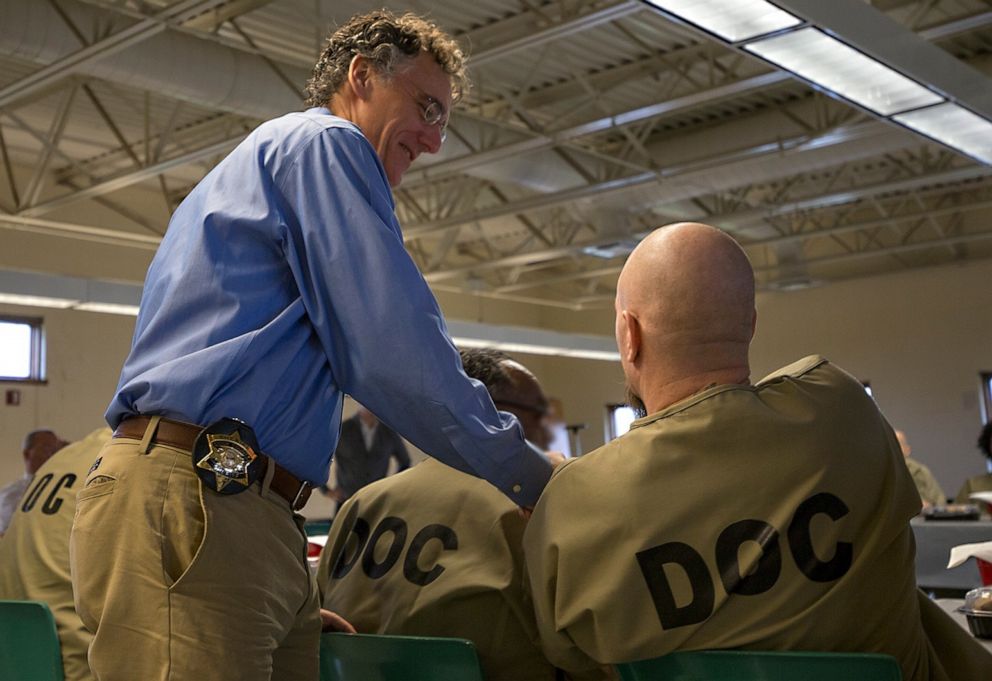

Dart, who was first elected to the office in 2006 and has seen first-hand the effect gun violence has had on communities, said mental health also plays a role. He started a series of mental health programs to help the inmates in his jail, like the Sheriff’s Anti-Violence Effort, or SAVE program. It offers intensive therapy and life-training skills for 18 to 24 year-olds who live in the county's 15 most violent-prone zip codes.

"They spend eight hours a day going through cognitive programming, we tweak it every once in a while but it’s a pretty solid plan that we’ve had going for about five years now," Dart said. "It (targets) what we and experts have suggested are some of the triggers for violence."

Dart also developed a Mental Health Transition Center, a place that offers a complete schedule of behavioral treatment like cognitive programming, anger management, therapy, meditation, parenting classes, and a discharge process so there's a hand-off to the community.

Oftentimes, police are the ones who are called when someone who has a diagnosed mental health condition is in crisis. That's why Dart said he makes sure his officers get training and why he developed a unit called Treatment Response Teams.

"We now have iPads, that our police officers have, so when they go to a mental health case, we literally hand the iPad to the mother or father or we’ll actually hand it to the person in a mental health crisis, and they’re sitting on the iPad talking to a mental health professional," Sheriff Dart said.

Although most of the attention given to guns and mental health focuses on mass shootings, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on average, 60% of all the gun deaths in the United States are suicides.

Linda Cavazos, a gun violence survivor and advocate, lost her brother Louie to gun suicide when he was 26 years-old. She said Louie was experiencing depression and anxiety over job loss and a relationship issue before his death.

"All five siblings got phone calls that day from Louie," Cavazos said. "It wasn't unusual for him to call. He sounded like Louis. I realized later that he was sentimental and I realize now that he was saying goodbye."

The death changed Cavazos' family, and their mental health, forever. She said her father became a shell of the man he was for at least five years. The brother who found Louie withdrew and his personality changed, Cavazos said while another brother felt anger and hurt for years. She and her sisters were left with feelings of grief, shock and survivor's guilt.

Cavazos said not only did the family not know Louie was having suicidal thoughts, she also said he lied to a friend to get the gun.

"The friend basically left the gun unsecured with ammunition and told him that he wasn’t going to be home and to come over and get it," Cavazos said.

It's one reason she is pushing for more secure storage laws and what's known as Red Flag laws. Nineteen states plus Washington, D.C., have passed Red Flag laws, which Swanson said lets police or a family petition a court to temporarily remove guns from someone who poses a threat to others, or themselves.

"Even if you’re someone who says ‘guns don’t kill people, people kill people,’ here’s a law that’ll help you figure out who those people are," Swanson said.

According to the non-profit Gun Violence Archive, the country has seen nearly 11,000 gun violence deaths so far this year. Last year, that number was more than 19,402, the highest number of gun violence deaths in more than 20 years. That was during the height of the pandemic when there were fewer mass shootings, the overwhelming majority were gun suicides.

If you are struggling with thoughts of suicide or worried about a friend or loved one help is available. Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 [TALK].

This story is part of the series Gun Violence in America by ABC News Radio. Each day this week we’re exploring a different topic, from what we mean when we say “gun violence” – it’s not just mass shootings – to what can be done about it. You can hear an extended version of each report as an episode of the ABC News Radio Specials podcast. Subscribe and listen on any of the following podcast apps: