Government predicted, but failed to address, racial disparities in global pandemic: Ex-officials

In late May, weeks after Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey officially reopened his state, Kristin Urquiza had a conversation with her father, Mark Anthony, about the coronavirus pandemic.

As a 65-year-old Latino, he was in a high-risk category and should remain isolated, she told him. “Why would the governor say it was safe if it wasn't safe?” he retorted.

Two weeks later, on June 11, Mark Anthony woke up with a fever. By June 30, he was dead.

Urquiza has laid the blame for her father’s premature demise at the doorstep of state and federal officials who she said “downplayed the virus and created a culture where people didn't know what to do.” In a powerful obituary, she wrote that Mark Anthony’s “death is due to the carelessness of the politicians who continue to jeopardize the health of brown bodies.”

The devastating toll of the coronavirus on communities of color has emerged as a crisis within the crisis. The disease’s outsized burden on racial minorities is due in part to preexisting health inequities, a higher likelihood of underlying disease, less access to insurance, and that a high percentage of people in these groups work in essential jobs that place them at higher risk of exposure.

Tune in to ABC on Tuesday at 9 p.m. ET for the "20/20" special report "American Catastrophe: How Did We Get Here?"

With new cases and deaths disproportionately mounting in Black and Latino populations, experts believe the phenomenon was both predictable and preventable.

An ABC News investigation found that so called “playbooks” drafted by prior administrations anticipated disparate outcomes along racial and economic lines in the event of a global pandemic. Public health experts who worked closely with Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama called this tragic reality “easily foreseeable.”

“One thing that all the pandemic plans identified,” Ron Klain, the Obama White House’s Ebola response coordinator from 2014 to 2015, told ABC News, “was that people of color would be disproportionately hit by a pandemic.”

Klain described the playbook as “a step-by-step process for ramping up a response, for ramping up testing, tracing, all the things that were needed.” He added that when Obama left office, a copy of it “was left for the Trump administration.”

“It said on the front ‘Pandemic Playbook,’” Klain explained. “And on page nine of the pandemic playbook, it said, ‘Hey, here's something to worry about: a coronavirus.’”

Dr. Julie Gerberding, the director of the Centers for Disease Control from 2002-2009, added that the Bush administration penned a similar plan that emphasized the “importance of testing and diagnostics” and a need “to stockpile antivirals at the state and local level.”

“I don't know if the Trump administration didn't pay attention to the playbook, I don't know if they didn't read it, I don't know if they read it and ignored it,” Klain added. “But what we do know is they didn't run the plays in that playbook, and it would have made a big difference if they had.”

In interview with ABC news, the nation’s top health officials acknowledged the stark racial disparities at play.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the government’s leading infectious disease expert, said it’s “tragic” but a “fact” that low-income and minority populations “have a higher incident of the underlying comorbidities that put them at greater risk of having a poor, serious outcome to getting infected.”

“Those are things that, for decades, have been more prevalent in minorities, including, and particularly, African Americans: diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, kidney disease, obesity,” Fauci said. “So they got hit what I call a double whammy. They became more susceptible because of what they do and how they live their lives out of necessity. And then once they get infected, they have a greater chance, purely on the basis of their comorbidities, to have a negative outcome.”

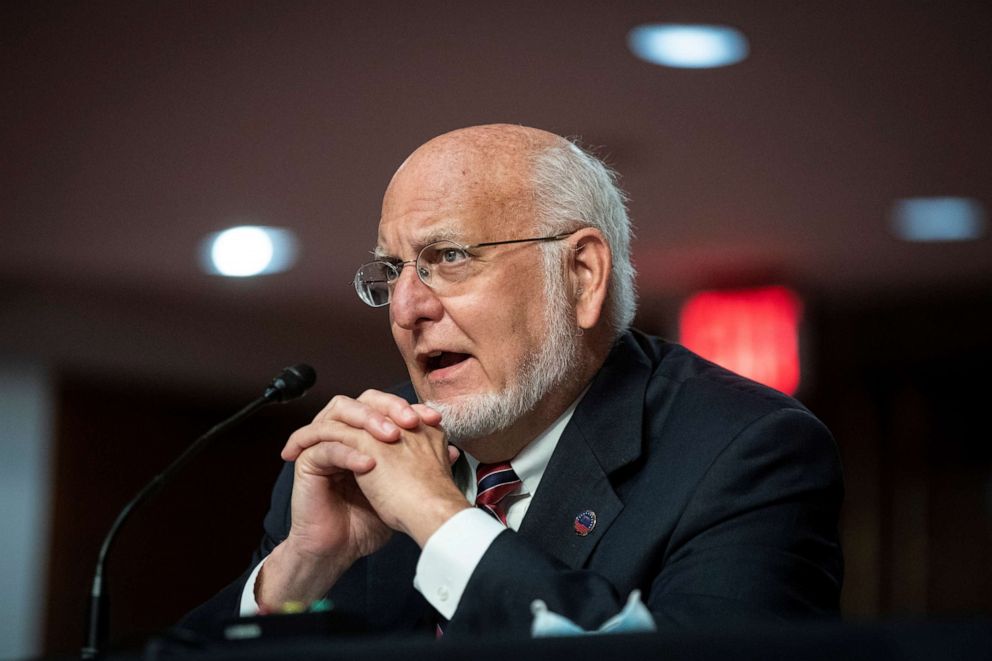

Robert Redfield, the director of the Centers for Disease Control, said health inequity is “one of the greatest social injustices we have in the world today” and “our inability to confront effectively that health inequity has enormous consequences.”

FEMA Administrator Pete Gaynor also recognized the toll of the virus on people of color, but insisted that his agency was “not blind to this at all,” and added, “I think we were pretty proactive.”

Gaynor cited the federal government’s deployment of crisis counselors, food deliveries to those vulnerable communities, and posting a civil rights bulletin meant to ensure that “the resources that were delivered to those impacted by COVID-19 was done in a fair way.”

But critics say the federal response was slow and the actions taken insufficient. Dr. David Satcher, a former U.S. surgeon general who is now a professor at the Morehouse School of Medicine, was blunt in his assessment.

“I don't think we've done as well as we needed to, and that's why the death rates have been so much higher in those groups,” Satcher said. “I think it was a failure in terms of an optimum response to this pandemic.”

In 2009, Dr. Sonja Hutchins, a former CDC official who is also now a professor at the Morehouse School of Medicine, co-authored a report which prophesied that “increased risk of adverse health outcomes is likely among minority populations during a pandemic.”

“Historically, we do know that minority populations, low income populations, are at increased risk for exposure during a pandemic of influenza,” Hutchins told ABC News. “So there is no surprise that we would see the same patterns. We saw it with Hurricane Katrina. We saw it with pandemic influenza of H1N1.”

For the first few months of the pandemic, the federal government did not release nationwide racial and ethnic demographics data on cases and deaths, delaying health experts’ ability to comprehend the extent of the impact of the pandemic on communities of color.

But disparate impact of the disease on communities of color is now clear, reflected in troubling statistical imbalances -- where race and ethnicity are known – in both infection rates and outcomes, according to figures gathered by city, state, and federal agencies.

Black Americans, for example, make up just 13% of the total population, but account for 20% of cases and more than 22% of COVID-19 deaths across the country. Similarly, Hispanics make up just 18% of the population, but account for nearly 33% of cases and 17% of deaths. Non-Hispanic White Americans, however, who make up 60% of the total population, have tallied just 37% of the cases and 50% of deaths.

It is emblematic, experts said, of existing inequalities in the economy, society and, especially, the healthcare system. Communities of color and populations at the low end of the socioeconomic scale struggle with access to healthcare during normal times. With the onset of the pandemic, those imbalances have been exposed and exacerbated.

“Unfortunately, the disproportionate impact that we've seen in minority and underserved communities is reflective of our health system at baseline as a whole,” said Dr. James Lawler, a former National Security Council official during both the Bush and Obama administrations who worked specifically on pandemic preparedness. “We know already that those communities unfortunately have disparate health outcomes. They have much more limited access to adequate health care, to preventive services.”

The availability of diagnostic testing -- a fundamental public health step in curbing the spread of the virus – has emerged as a particularly poignant example. A joint investigation by ABC News, FiveThirtyEight and ABC-owned stations revealed that testing resources were more scarce in predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods than in predominantly white neighborhoods.

That imbalance in testing sites, the analysis showed, reflects a long-standing gap in the existing healthcare system and an unequal distribution of healthcare facilities. As expected, when the coronavirus began tearing through those underserved communities, the problem was compounded.

In the early stages of the pandemic, “It was very challenging for anybody to get a test,” said Scott Becker, the CEO of the Association of Public Health Laboratories. But during that same time period, he said, “it was near impossible for individuals in [Black and Latino] communities to get a test.”

Access to insurance is another symptom of inequality in healthcare that the pandemic has amplified. According to a census data released in 2018, Black and Latino Americans are far less likely to be insured.

Hutchins said even when racial minorities do have access to testing, for example, “there are still people who don't have health insurance and believe that it's going to cost them money if they go get a COVID test.”

Fauci and other experts also pointed to economic realities at play. Many people of color have essential or frontline jobs, Fauci said, leaving them with “a greater likelihood of actually getting infected.”

Klain, the former Obama administration Ebola czar, said minorities tend to make up a significant cross-section of the economy that has been put in harm’s way so the rest of Americans can remain isolated and safe.

“For some of us to stay at home, other people had to go to work,” Klain said. “And what's pretty clear is a lot of those jobs are some of the least well-paid, least well-protected, least health benefits, and other kinds of benefits of all the jobs in our society.”

Tune in to ABC on Tuesday at 9 p.m. ET for the "20/20" special report "American Catastrophe: How Did We Get Here?"

Dr. Mary Bassett, a former NYC Health Commissioner from 2014 to 2018 who is now a professor at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health, posited that, “if you got up early in the morning in New York City and got on the subway in those days, I can guarantee you that the people riding those trains would be overwhelmingly Black and Latino.”

Meanwhile, in the South and West, many Latino workers work in the agricultural industry – a particularly essential line of work with major implications for the country’s food supply.

“The Hispanic community is one where there's a lot of essential workers, the people that work in areas where they are, for example, processing food, or with vegetables or fruits,” said Dr. George Diaz, the infectious disease chief at Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett, Wash. “People that we can't afford not to have work.”

In June, the Department of Health and Human Services released a comprehensive strategy to address the disparate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups, including expanding accessible community testing in disadvantaged neighborhoods as well as affordable treatment and care to uninsured and underserved communities.

For his part, Redfield, the CDC director, hopes that the pandemic can be used as an opportunity to address existing health disparities in communities of color – a silver lining in the aftermath of an otherwise devastating time.

“I think first step is to recognize it's real, that it's not right,” Redfield said. “And that it is possible to change. And we need to do that.”

ABC News' Ely Brown, Tonya Simpson, Lauren Dimundo and Ava Anderson contributed to this report.