'It changes everything': George H.W. Bush's legacy and one man's life with disabilities

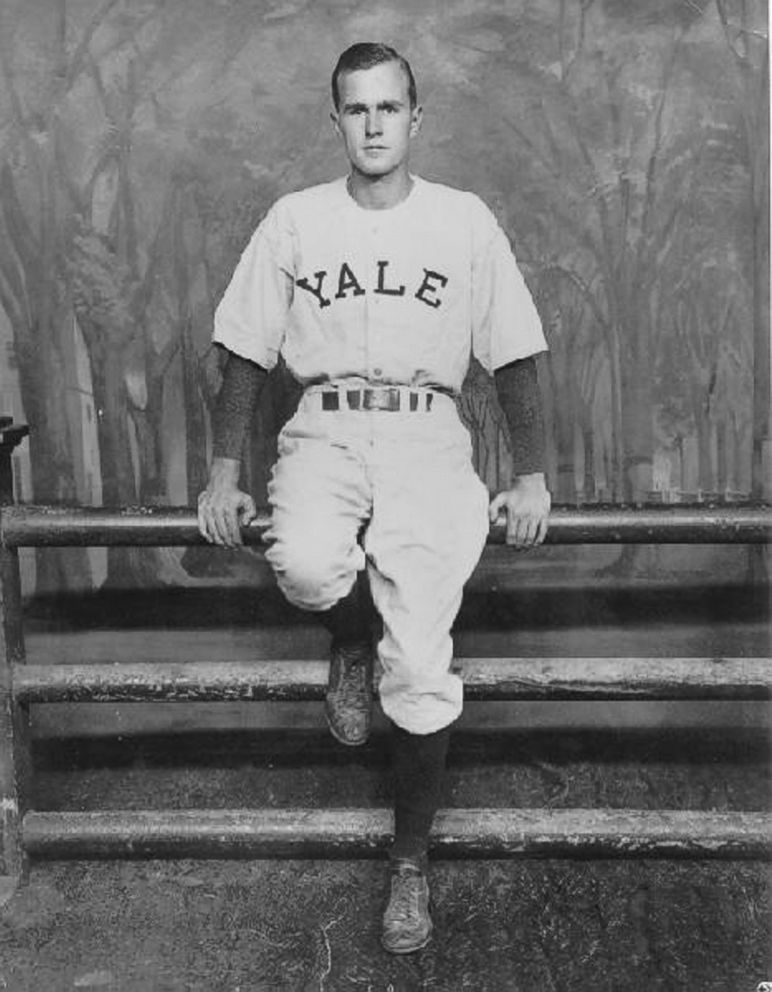

Almost 30 years ago, Paul Smith traveled to the nation’s capital to watch as the 41st President of the United States took the oath of office and his place in history.

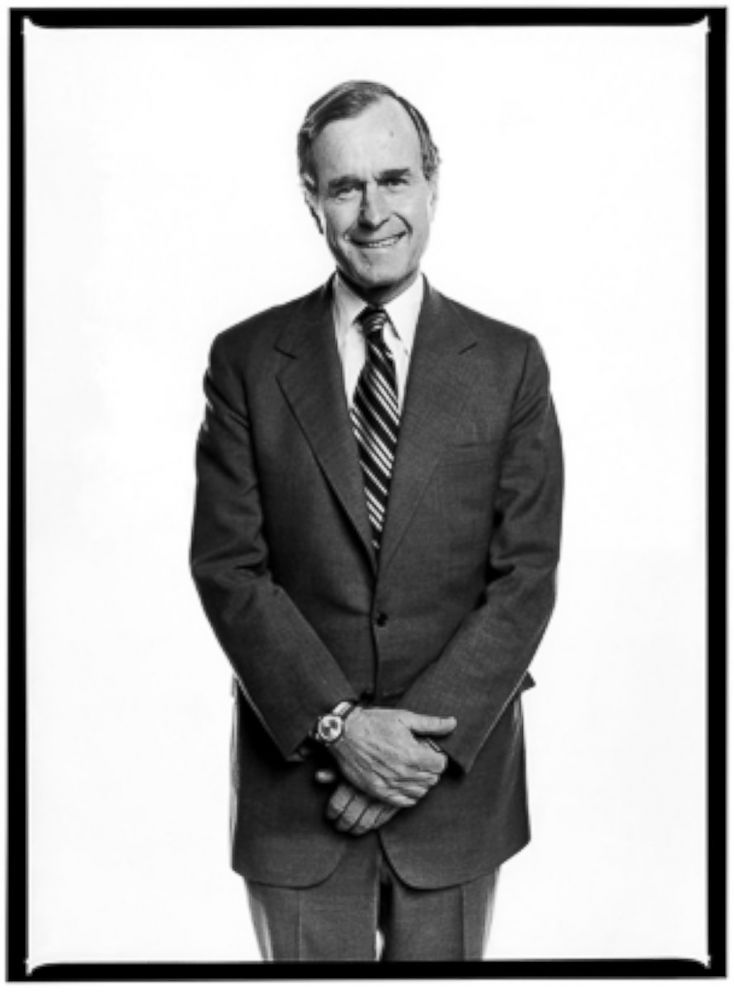

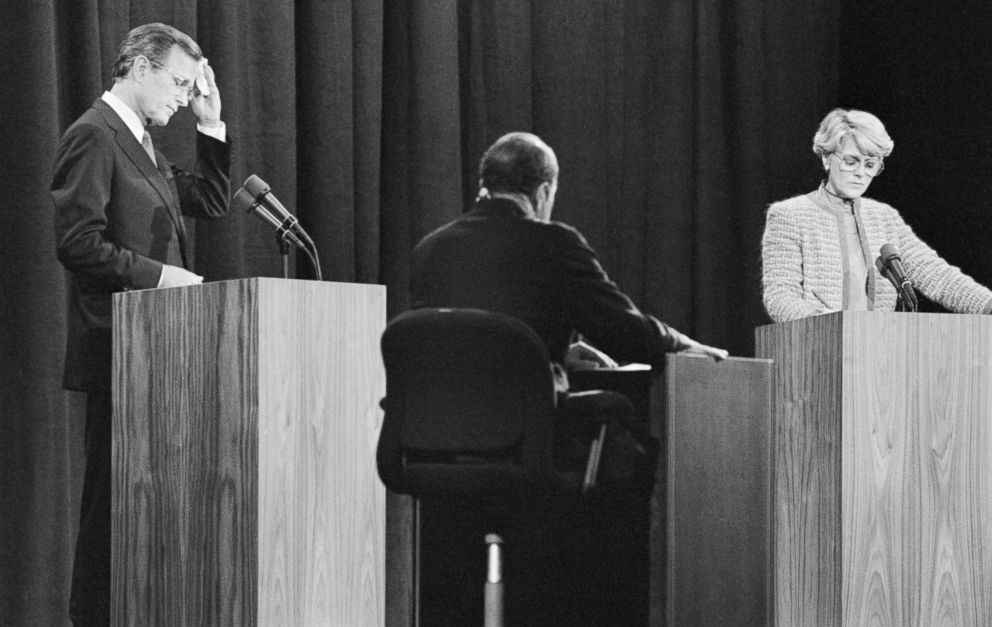

It was Jan. 20, 1989 — the day President George H.W. Bush was inaugurated. Already, Smith admired Bush as a “strong, silent type” who “didn’t need credit for what he did, as long as it got done.” But he didn’t know then how the president would have such a direct impact on his life — and the parallel challenges both would eventually face.

Bush used a wheelchair in his final years and Smith has lived with physical disabilities for two decades, ever since a car accident left him with a shattered knee that would eventually require two replacement surgeries. Smith didn’t know when he was watching the 1989 inauguration that, as president, Bush would sign the Americans with Disabilities Act, a landmark law that prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities.

“It affects me more because I’m in this position now, but just like Lyndon B. Johnson and the Civil Rights Act, it’s one of the cornerstones of equal rights for people,” Smith said of the 1990 law. “It gave freedom to people who didn’t have it before.”

On Tuesday, Smith, 52, returned to Washington, D.C., on the crutches he’s used on-and-off for about two years to pay his respects to Bush as he lay in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda.

He didn’t have the ease of mobility he had 30 years ago, and he was already feeling swelling in his knee from the red-eye flight he’d taken from Salt Lake City, Utah, that departed the night before. In fact, Smith didn’t even tell his wife he planned on making the trip until he was at the airport, he said, because he knew she’d tell him not to risk the issues it might cause for his knee.

“I ran away,” Smith, a self-described “history buff,” said with a laugh. “You’ve gotta do stuff like this every once in a while.”

While he was on the plane, he worried to himself about all of the stairs up to the Capitol Rotunda. But then he remembered: “Things have probably changed,” he said.

Smith, who lives in Tooele, Utah, has attended many inaugurations — and taken his children to a few, he said — but has never seen a president lying in state. He decided the physical challenges would be well worth the “rare opportunity to witness history up close.”

“It’s a lot different now than it was 20 years ago,” Smith said after he arrived in the Capitol Visitor’s Center, referring to the accommodations built after passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. “Now there’s practically nowhere I go where I’m without an elevator or without a plan.”

“It makes it so I can do things like this,” Smith said.

Smith was familiar with the act's importance when it was signed back in 1990, and, like Bush, encountered people every day through his job who were affected by it. Before taking disability leave, Smith worked in customer service for Delta Airlines for 31 years.

“I see it totally differently from this side,” Smith said. Bush, for whom the issue was already personal because his daughter Robin’s physical difficulties and, later, his son Neil’s learning disabilities, expressed the same sentiments once his battle with a form of Parkinson’s disease left him wheelchair bound.

“It changes everything you do,” said Smith, who used to ski in Utah three times a week before his accident. “But it doesn’t mean your life is over. I mean, here I am in Washington.”

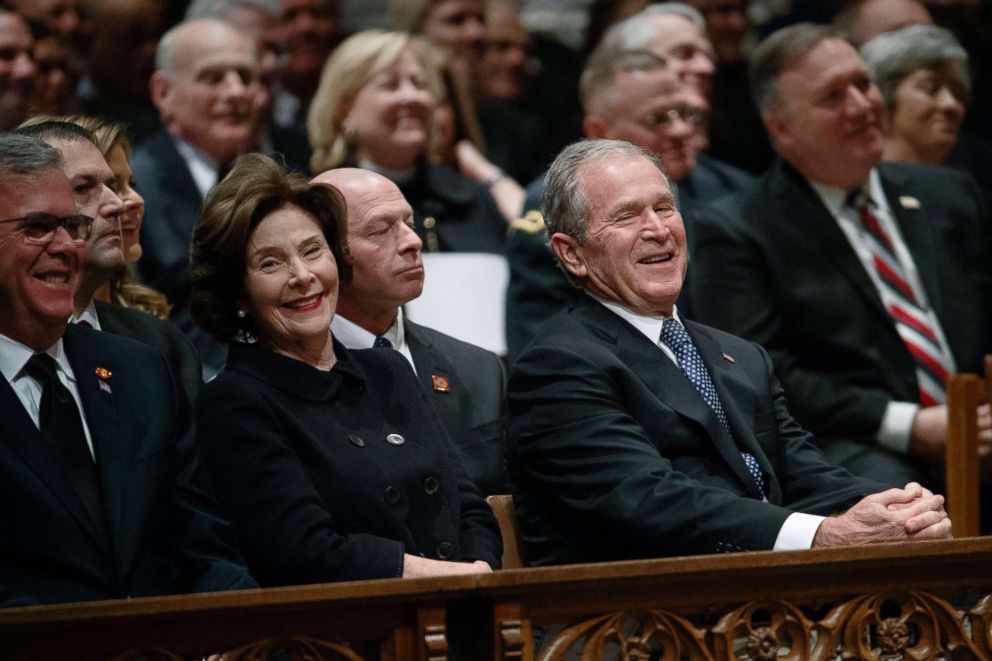

Honoring former President George H.W. Bush

Memorials to the 41st president as he's laid to rest.Smith waited in line for about an hour before he got in an elevator up to see Bush’s casket. Soon after he entered the Rotunda to pay his respects, members of the military performed a slow, dignified changing of the guard.

Smith welled up, wiping tears from both eyes.

“It’s really emotional,” he said. “I was overcome.”

“There I was, standing five feet from it all,” he said, describing people around him from “all walks of life” who had stopped to take a minute and pay respects to the president — “how it’s supposed to be,” Smith said.

As he left, a U.S. Capitol Police officer pointed him to an elevator. Another asked if he’d had any trouble finding his way.

“I couldn’t do this if they didn’t have the accommodations,” Smith said as he got in line to sign a condolence book for the Bush family.

Next to a note written by a woman who’d made the trip to D.C. from Florida, he thanked the late president for “the great example of what a good leader should be.”

“You ran the good race, you fought the good fight. Welcome home my faithful servant," Smith wrote. "You will be missed!”