Ferguson: A Look Back at Michael Brown's Death

— -- One of the things I remember most from our time in Ferguson a year ago is the strong smell of the smoke still in the air the night after the shooting of Michael Brown Jr.

The looting and burning of the Ferguson QuikTrip became a flashpoint in the unrest that engulfed Ferguson in the days and weeks after the shooting. The images of young black people, running in and out of that store with armfuls of stolen chips and beer, were unsettling and provoking. If it weren’t for this lawlessness -- and that’s what I still call it -- it’s unlikely the death of this young black man at the hands of a white police officer would have ever led to the igniting of a movement, and the burning of parts of the city.

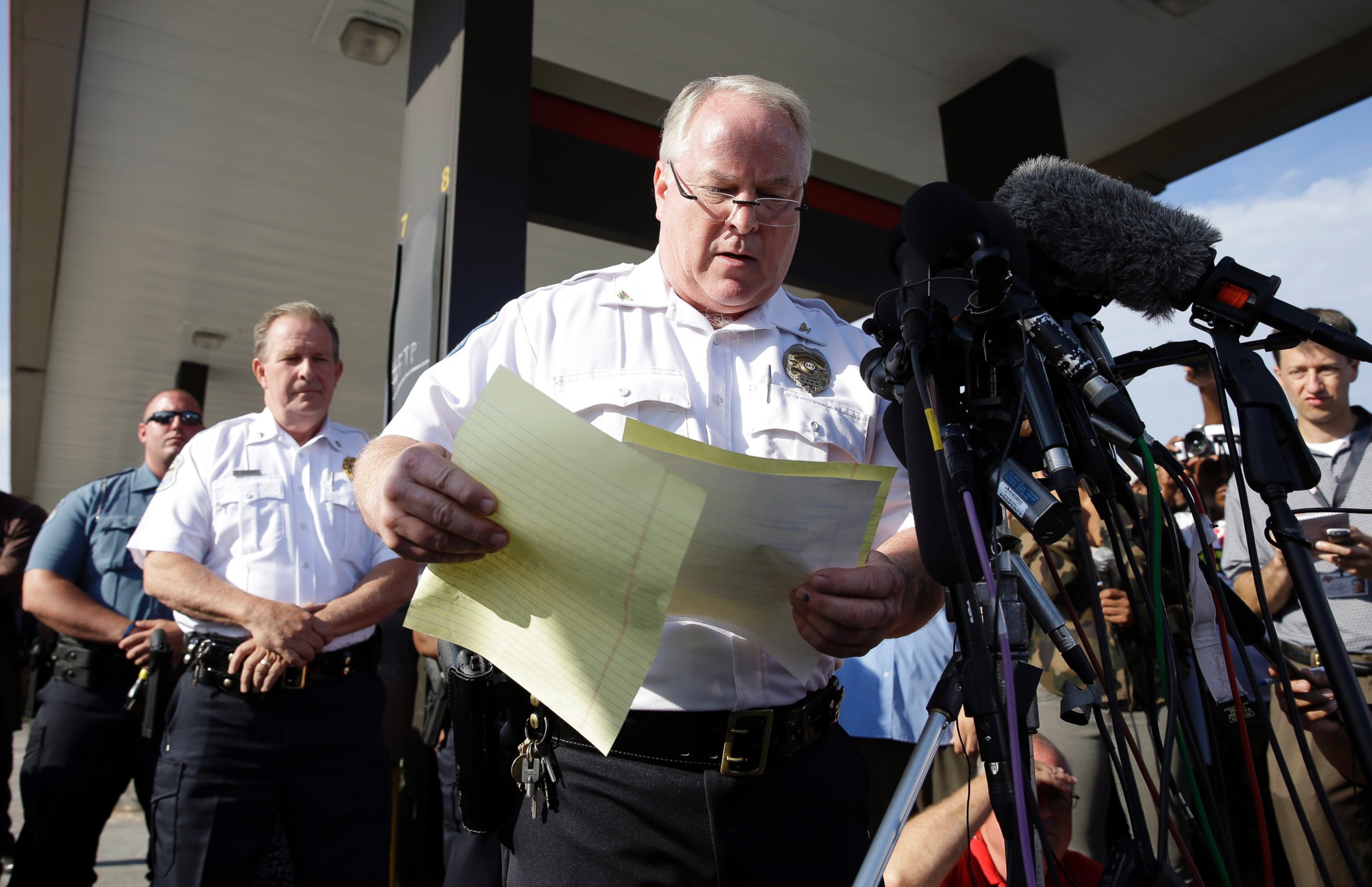

I got close to Ferguson Police Chief Tom Jackson. And while I firmly believe that two people can have entirely different experiences with the same person, the man I met and interacted with didn’t fit the awful description I was hearing on the streets. To me, he did not resemble at all the racist police described in those damning reports from the Department of Justice. But for many on various sides of the issue, it’s just easier to demonize.

What I saw was a man who was overwhelmed, who couldn’t offer the best salaries and was frustrated that the interaction between Officer Darren Wilson and Brown had to end with someone dying.

By Tuesday, three days after the Aug. 9, 2014 shooting, the medical examiner publicly shared preliminary autopsy results, but Chief Jackson still wasn’t yet releasing Wilson’s name. That wouldn’t come until Friday.

“Given the threats and way social media has played out,” he said on Tuesday, “we think that the value that might have been gained by releasing the name is far outweighed by the risk of danger at this point."

For many, Chief Jackson and the Ferguson PD in general waited too long to answer simple questions. Why was Michael Brown’s body left in the street for hours? And if Officer Wilson was injured in a physical struggle, why wouldn’t police show his injuries right away? None of this was helping repair years of local distrust with authorities. I heard stories from young black men that mirror my own. Pulled over by police for no good reason.

Across America, so many in the black community can relate to Sandra Bland, who was pulled over by a police officer. And the panic that begins long before the lights start flashing, as the driver whispers, “I know I didn’t do anything wrong.”

In Ferguson, Shirley Davis told me she fears for her own son.

"I have a son that’s 27 with dreads down to here and I have to talk to him every day: 'When you are stopped by the police you don’t say a word.' We should not have to do this. We are citizens of the U.S.A.'"

I jokingly call these police encounters "shaking the tree," as in to see what fruit falls. And the young people who are living through this today found their voice on the streets of Ferguson. And they’re not speaking quietly.

They were particularly loud in Baltimore in response to the death-in-police custody of Freddie Gray.

As an African-American reporter, covering these stories requires thick skin. People in my own community have called me an Uncle Tom, at the same time others are calling me a racist, all after watching the same story.

For me, Ferguson underlines this: That the argument over policing in America remains an incredibly polarizing and explosive issue with no easy answers.