A family's desperate search for a missing young woman highlights questions about justice on tribal lands

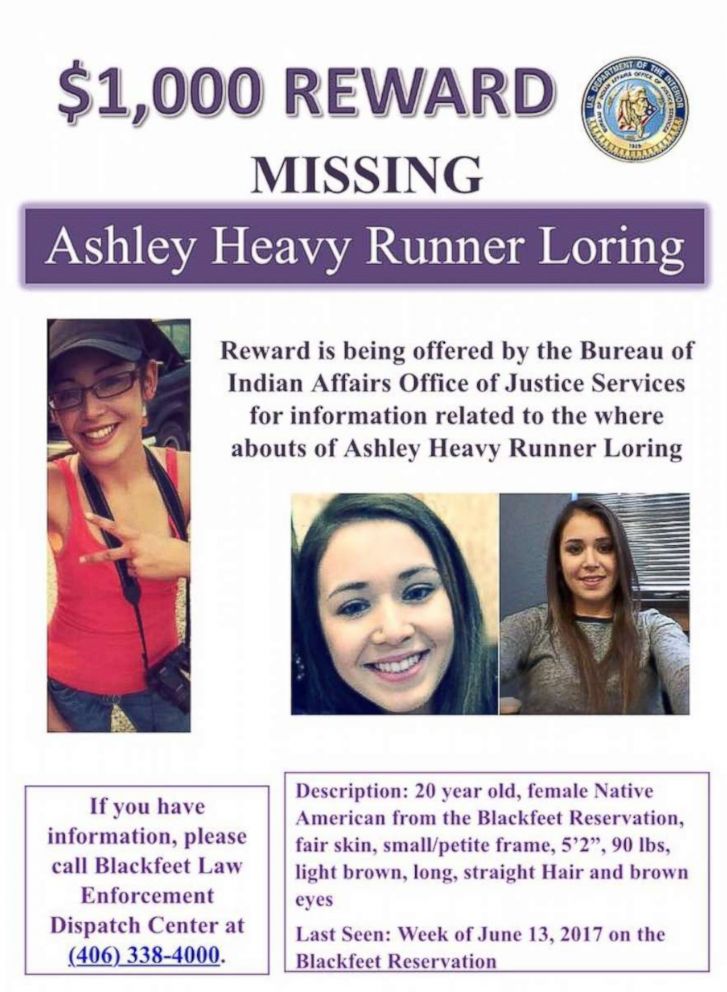

— -- When Ashley Loring HeavyRunner, a 20-year-old college student, vanished from the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana this summer, her older sister Kimberly Loring thought of a promise she once made.

“When we were young, we were in the foster care system,” Kimberly Loring told ABC News. “She told me, ‘Don’t leave me,’ and I told her, ‘I would never leave you, and if you were to get moved, I will find you.’”

Kimberly Loring said she was only 8 years old when she made that promise. But 15 years later, with her sister missing for more than four months, she said it now seems more important than ever.

“I’m going to keep this promise. Wherever she goes, I’m going to find her,” Kimberly Loring said. “If I have to search my entire life, I will search until I find her.”

Kimberly Loring said she learned of her sister’s disappearance in early June, after returning home from a vacation abroad. The sisters had been planning to move Ashley Loring into her sister’s apartment in the nearby city of Missoula, where Kimberly Loring had landed a good job working with senior citizens. Kimberly Loring said she expected to hear from her little sister the moment she got off the plane, but she didn’t call that day or the next or the day after that.

“I tried to call Ashley, and she didn’t text me or anything. There was no response from her,” Kimberly Loring said. When she couldn’t reach her, she said she began reaching out to her sister’s friends on social media, but none of them had seen her since June 5.

“She was waiting for me, and I know she wouldn’t up and leave,” Kimberly Loring said, adding that her sister was extremely close with her family members and would have told them where she was going. Friends and other family members also told ABC News that it was unlike her to go so long without contacting anyone.

“Something happened to her,” Kimberly Loring said.

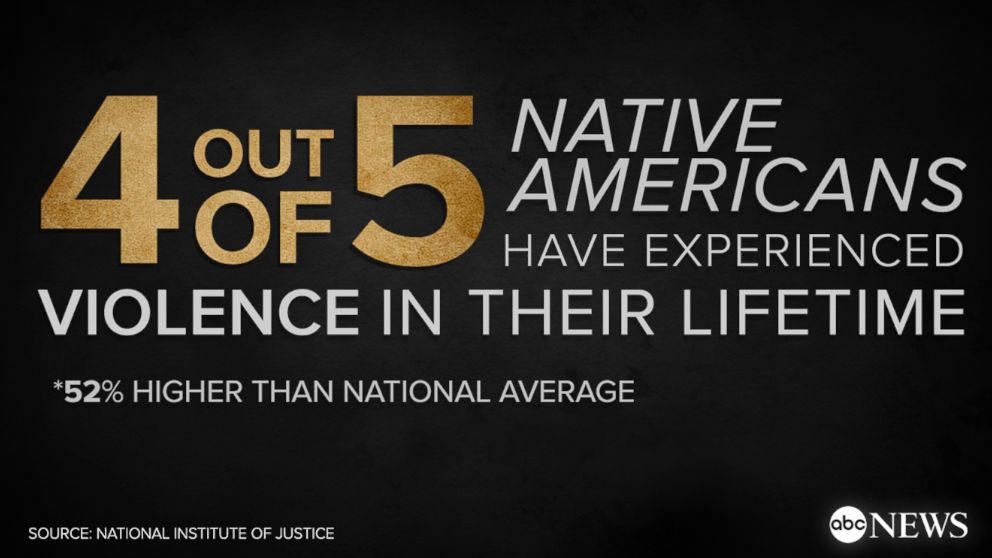

Native Americans living on reservations face violent crime rates two and a half times the national average, according to a New York Times analysis of 2012 Department of Justice data.

Native American women are especially vulnerable.

The same analysis by the Times found that Native women are 10 times as likely to be murdered than non-Native Americans. Native women are raped at a rate four times the national average, according to the data, with more than 1 in 3 having been the victim of rape or attempted rape.

More recent data shows that more than four in five Native Americans have experienced violence in their lifetime, which is 52 percent higher than in the general population, according to a 2016 National Institute of Justice report.

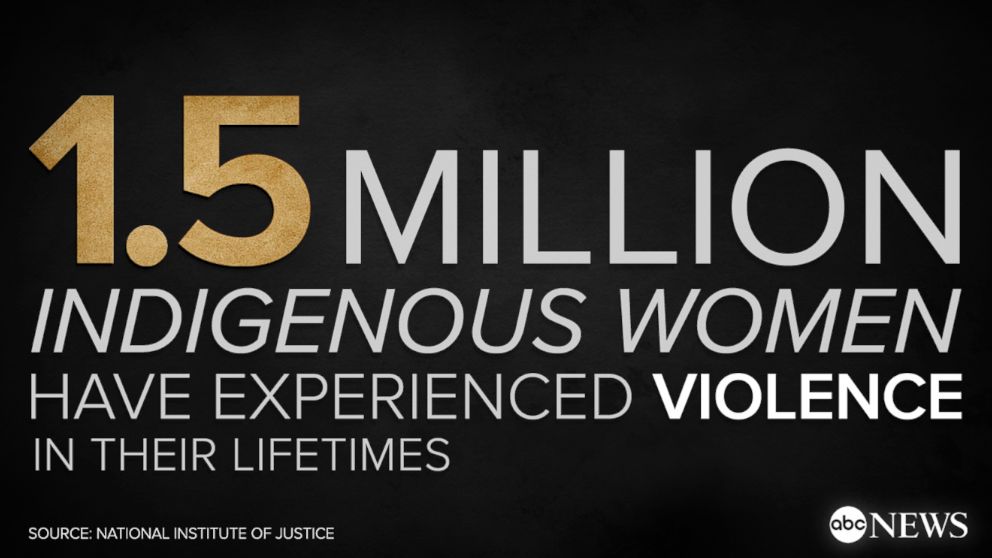

The same report found that 84 percent of indigenous women have experienced violence in their lifetime, with more than half experiencing sexual violence.

The NIJ report also said that more than 1.5 million of today's indigenous women have experienced violence in their lifetime — 730,000 of them in 2015 alone.

This is the context in which Ashley Loring disappeared, her sister said.

“I don’t want to be an 80-year-old woman searching these mountains with my grandchildren,” Kimberly Loring said. “But there’s no choice, because if I give up, who’s going to look for her?”

Since Ashley Loring’s disappearance, Kimberly Loring quit her job in Missoula and moved back home to the reservation to help look for her. Family members filed a missing person report with tribal police in mid-June. More than four months later, they said they still have not heard from her. Tribal police have also been unable to find her.

Blackfeet Law Enforcement Services, the tribal police, did not respond to ABC News’ request for comment by the time of publication.

‘She blew everyone out of the water’

Growing up, the Loring sisters spent several months in foster care before going to live with their grandparents and their other siblings. Life was much better on their grandparents’ horse ranch, Kimberly Loring said. The sisters learned how to ride, chopped wood for their grandmother’s wood stove, mucked stalls and swam in a nearby creek until well after the sun disappeared behind the high plains.

“She was a good girl. We didn’t have no trouble with her,” Loxie Loring, the girls’ grandmother, said of Ashley. “I could count on her to get a little more work out of her than the other two.”

Since Ashley Loring disappeared four months ago, Loxie Loring said she has barely left the house. She said she sits by the phone for most of the day, waiting for her granddaughter to call.

As a student at Blackfeet Community College, Ashley Loring was once asked to give a presentation at a college in Bozeman about buffalo, her ex-boyfriend Calvin DeRouche said. Her speech earned her praise across the reservation.

“She blew everyone out of the water,” he told ABC News. “She’s outgoing, and she’s smart. She was beautiful. Just everything that you can look for in a person, she had it.”

For months, Kimberly Loring said she has been putting up flyers, scouring through social media for clues and fielding anonymous calls from tipsters, desperately hoping someone will speak out about what happened to her sister. Nearly every other day, she organizes search parties in the Rocky Mountains lining the western edge of the reservation. She said she has conducted more than 40 searches in this remote region, which is home to grizzly bears and mountain lions.

In the weeks after Ashley Loring’s disappearance, Kimberly Loring said, law enforcement helped her search the mountains, but now, she said, they rarely show up when she calls for assistance.

Now working largely on her own, she has moved back in with her grandmother. But it has been a frustrating time, she said.

“I was only supposed to be here for four days, and now it’s almost four months,” Kimberly Loring said.

A long history of unsolved crimes

Carl Kipp, a Blackfeet Tribal Business Council member and the chairman of the tribe’s law and order committee, said there is a history of unsolved violent crimes on the reservation. The business council is the governing body on the reservation.

“That’s been going on for decades — unsolved murders or lack of investigations,” he told ABC News.

But Kipp said Blackfeet Law Enforcement Services, which is now working with investigators from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, is doing everything it can to find Ashley Loring.

“Every lead that they get, they follow up on it,” he said.

When asked about the lack of progress on Ashley Loring’s case in the months since she was reported missing, Kipp said the tribe’s police force is stretched “pretty thin.”

According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the force has only 15 officers and four sergeants, who are responsible for patrolling more than 1.5 million acres of reservation land, an area larger than Delaware.

“We need a minimum of 30 officers, based on federal statistics,” Kipp said, adding that the funding the police force receives from the BIA is not enough to properly staff it.

Nedra Darling, a spokesperson for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, told ABC News in a statement, “The Blackfeet tribe and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Office of Justice Services has continually conducted law enforcement investigations on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation since around the 1960s in one form or another via tribal police/BIA.”

“Both the Blackfeet tribal police department and the BIA/OJS continue to work together with all the resources available to bring Ashley home,” Darling added.

In their efforts to find Ashley Loring, Darling wrote, law enforcement officials have conducted approximately six searches and 60 interviews and offered a financial reward for information relating to her disappearance. Darling added that law enforcement has identified several people of interest and identified suspects.

But the issue of unsolved crime appears to be widespread, according to locals. Blackfeet Reservation residents who requested anonymity, for fear of retribution, told ABC News of at least six other suspicious deaths dating back to the 1970s that they said have never been solved.

In her statement, Darling acknowledged that there is one additional unsolved missing person case from the 1970s.

But Kipp said there are also unsolved violent crimes, such as the case of Matthew Grant, a young man who was found dead in an alleyway on the reservation early this year, ABC’s Montana affiliate reported.

According to Kipp, no one has been arrested for Grant’s death.

When asked about the reservation’s unsolved violent crimes, Kipp pointed to a lack of interest by the federal government, which the tribe largely depends on to charge and prosecute violent offenders.

“The lack of jurisdiction the tribal police has, that’s why we have such a big problem,” he said.

Questions of jurisdiction

Kipp is referring to a 1978 Supreme Court case that ruled tribal courts lack jurisdiction over non-Native people for offenses committed on tribal lands. The Violence Against Women Re-Authorization Act of 2013 partly changed that by providing federally recognized tribes that meet certain conditions with special jurisdiction over non-Native offenders involved in domestic violence cases.

But critics argue that act didn’t go far enough. For one thing, in some states, Public Law 83-280 prohibits tribal courts from charging any individual, whether a member of a tribe or a non-Native person, with a major crime. Montana opted into the program, and the law was passed without tribal consent, according to a 2013 report by the Indian Law and Order Commission to Congress.

The report found that “criminal jurisdiction in Indian country is an indefensible maze of complex, conflicting and illogical commands layered in over decades via congressional policies and court decisions and without the consent of tribal nations.”

According to the report, the results “extract a terrible price,” with delayed investigations and prosecutions, and lead to the “further endangerment of everyone living in and near tribal communities.”

‘I still have hope that she’s alive’

Last week, Kimberly Loring said, she received a tip to search the western slope of a nearby mountain. She said she is bombarded by tips about where to find her sister, and even though she said she knows they are unlikely to prove true, she dutifully follows up on each and every one.

Kimberly Loring mobilized a small group of family members and friends and headed off into the wilderness armed with walkie-talkies and a small arsenal of bear mace. ABC News accompanied them, and for hours the team combed the forest and a nearby ravine, turning over woodpiles and digging into mounds of earth. But the search, like so many before it, came up empty.

“I still have the hope that she’s alive,” Kimberly Loring said. “But what if she isn’t? What if she’s laying here? I wouldn’t want my sister to be laying anywhere in these mountains.”

As the search came to a close, Kimberly stopped to catch her breath on a rocky perch. With winter fast approaching, she knows she is running out of time before the snow will make it nearly impossible for her to continue searching the mountains. Friends and family said Kimberly has shown incredible bravery and composure in her search for her sister, but sitting on the rocks above the forest, she began to cry for what she said was the first time in months.

“I wish there was two of me, because I don’t know what I’m doing sometimes,” Kimberly Loring said.

Then she paused to catch her breath, raising her fingers to the corners of her eyes and squeezing hard to stop the flow of tears. After a moment, she collected herself and stood up straight.

“But I told my sister when we were little that I’d always be there and ‘If you go somewhere, I’ll find you.’ And that’s what I’m going to do,” she added.

Authorities ask anyone with information about Ashley Loring HeavyRunner to contact Blackfeet Law Enforcement at 406-338-4000.

ABC News’ Kaelyn Forde contributed to this report.

ABC News’ reporting on Ashley Loring’s case is ongoing. Check back for updates.