Facial-recognition software may be able to identify people based on brain scans

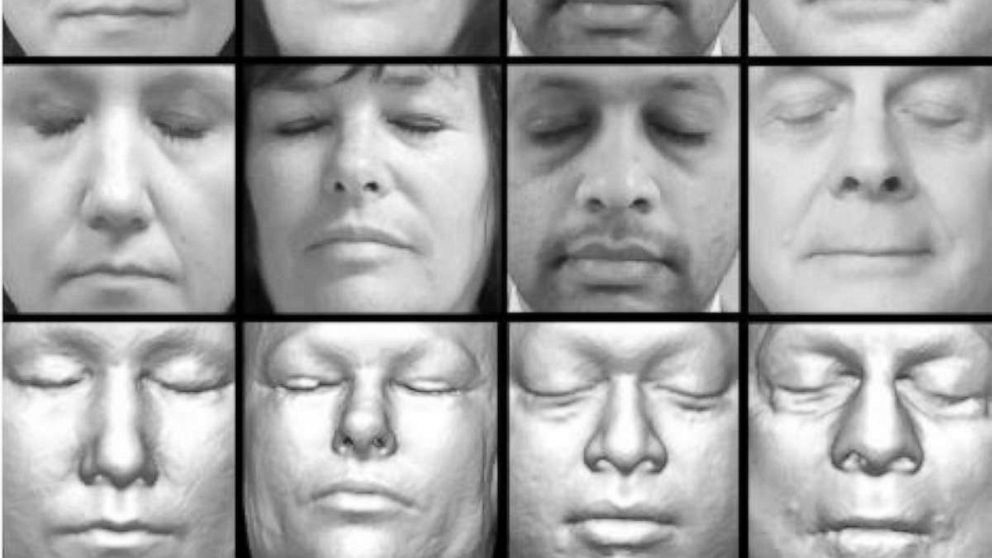

A new study has found that it might be possible to use commercial facial recognition technology to identify people based on MRIs of their brain -- even if researchers take the usual steps to protect patient privacy.

Publicly available facial-recognition software was able to correctly match photographs of people 83% of the time, on the first try, based only on their "deidentified" cranial MRI scans, researchers said in a letter published Wednesday in The New England Journal of Medicine. "Deidentified" means that identifiable information had been removed.

"This is only applicable if people can get access to the MRI scans in publicly available research databases. It is not related to medical care, where data is secured," the study's lead author Dr. Christopher Schwarz, a Mayo Clinic researcher and computer scientist in the Center for Advanced Imaging Research, said in a statement.

"We are studying potential gaps in deidentification as we seek ways to improve these techniques," Schwarz said.

The threat to privacy only applies to people who have released their MRI imagery to the public domain by, for example, participating in research studies.

Currently, researchers remove names and identification numbers when sharing MRI scans with others in the medical community, but doctors typically won't blur facial imagery because it can make it harder to automatically measure brain structures from the images, according to Schwarz.

As part of the study that included 84 volunteer participants, the correct photograph of a person's face was chosen as the facial recognition software's number 1 match with an 83% success rate.

"With advances in digital technologies, in this case, facial recognition software, it's critical that we continue to revisit the promises that we've made to our patients, particularly promises related to the confidentiality of their medical data,"

Dr. Richard Sharp, the director of the Biomedical Ethics Research Program, said in a statement about the findings.

"Much of our work in biomedical ethics focuses on protecting patients from unanticipated harms and this is an excellent illustration of the importance of that work," the statement added.

Schwarz added that they are making "good progress toward an initial solution," but noted that keeping patients' data private is an "always-evolving field."

"The insights we gained in this study will help us in our work to keep patient data private and use it more effectively for research into diseases and potential new therapies," he added.