FAA chief tells lawmakers aircraft certification system 'is not broken,' despite Boeing 737 Max crashes

Administrator Stephen Dickson, head of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is pushing back against the notion that the 737 Max crashes reveal that something is broken with the aircraft certification process.

Dickson's comments came during a House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee hearing on Wednesday, focused on whether there was proper oversight by the FAA -- the agency responsible for regulating civil aviation in the U.S. -- during the certification process for the 737 Max. It was the committees fifth hearing since launching an investigation in March 2019 into the Boeing 737 Max planes connected to two fatal crashes that killed a total of 346 people.

"The system is not broken," Dickson told Ranking member Rep. Sam Graves, R-Mo., but he did concede there is room for improvement. "With any process and I've said many times even in these last four months, all processes need to be improved."

Under the Organization Designation Authorization (ODA) program mandated by Congress, some of the aircraft certification process was delegated to manufacturers like Boeing. Critics of the ODA program say that delegation created a conflict of interest. However, others defend the program, saying there has been sufficient FAA oversight from start to finish during the process.

The agency is "not delegating anything to Boeing," Dickson reassured the committee.

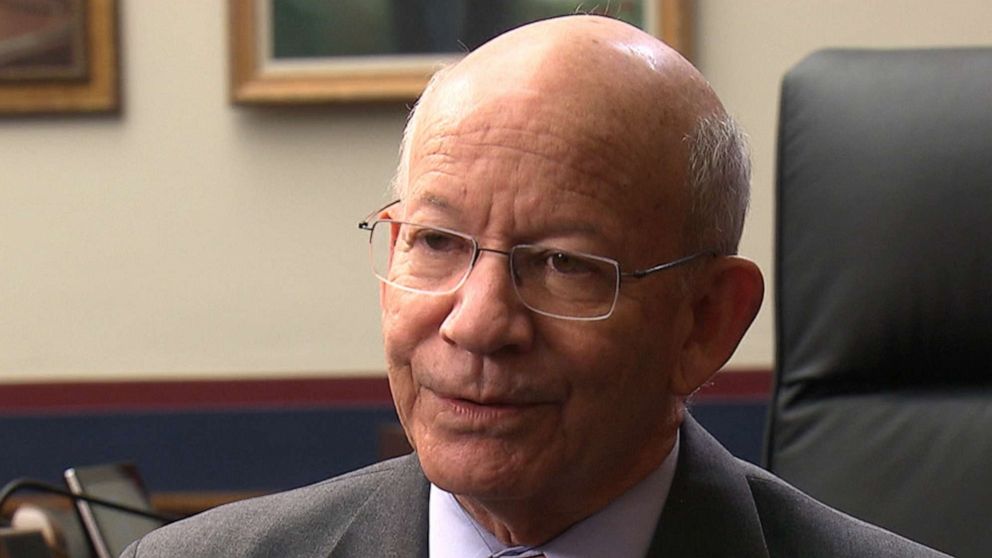

The committee's chairman, Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., said he " target="_blank">still believes the FAA “failed to do its job."

"The FAA trusted, but did not appropriately verify key information and assumptions Boeing presented to the agency about the 737 Max," DeFazio said in his opening statement.

DeFazio, backed up by other lawmakers, said he is prepared to implement legislation to strengthen government oversight over jetliner certification.

"We can certainly mandate changes in the approval process and the oversight process by the FAA," DeFazio told David Kerley, ABC News' senior transportation correspondent, on Tuesday. "We're already thinking of options of changes we might make."

737 Max certification stretches to 2020

Hours before the hearing on Wednesday, Dickson crushed Boeing's hope of getting the 737 Max re-certified before the end of the year.

“If you just do the math, it’s going to extend into 2020," Dickson said in an interview with CNBC.

The FAA grounded the 737 Max jets on March 13, and the agency has complete control over when the troubled plane will take to the skies again.

"When the 737 Max returns to service, the safety issues will have been addressed and pilots will have all the training they need," Dickson told lawmakers. "I'm not going to sign off on this airplane until I fly it myself."

In both crashes, it appears the angle-of-attack sensor was sending incorrect data, misfiring the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS, which pushed the plane's nose down repeatedly even as pilots fought to gain altitude.

House Democrats released a FAA risk report on Wednesday which showed the potential of more than 15 fatal crashes over the life of the Max fleet -- about 45 years -- if no change was made to MCAS.

The risk assessment was conducted after the first 737 Max crash near Jakarta, Indonesia. At the time there was already suspicion that the crash was related to MCAS, and the assessment was intended to establish a timeline for a MCAS fix.

Dickson admitted the report showed an unacceptable level of risk, but because the FAA had issued an Airworthiness Directive and the MCAS fix was already in the works, both the agency and Boeing determined the 737 Max fulfilled the requirements to continue flying after the first crash.

Five months later an Ethiopian Airlines flight crashed shortly after takeoff in Addis Ababa. Initial reports show the pilots were able to disable the MCAS system, but it was too late for them to regain control of the aircraft.

One of the software fixes Boeing has completed on the 737 Max is a change to rely on two sensors, not just one, to activate the MCAS. A second software fix is related to the overall flight-control software system.

Boeing's safety culture under scrutiny

Edward Pierson, a Boeing retiree, testified alongside Dickson on Wednesday, on safety concerns he claims were ignored regarding the 737 Max production line.

He said he was worried about the demand for workers to quickly produce the planes which might have led to injuries and mistakes.

DeFazio said he believes Pierson's concerns paint a picture of a company that put profit over safety -- though they weren't related to the plane software connected to the two crashes.

The lawmaker told ABC News in October that the committee has received "report after report about production pressures" inside Boeing, as part of its investigation.

"I fear that profit took precedence and put pressure on the whole organization all the way down," DeFazio said at the time.

Boeing has been accused of withholding information from the FAA regarding MCAS, including internal messages that surfaced in October in which the chief technical pilot for the aircraft, Mark Forkner, told another pilot that the MCAS flight control system was “running rampant” in a simulator session.

The documents released two months ago by the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee show Forkner told FAA officials that MCAS was safe after calling it "egregious" based on simulator tests, according to internal messages and emails.

In regards to areas like pilot training and manual recommendations, Forkner was the main point of contact between the administration and Boeing, an FAA official explained.

Boeing said in a statement that Forkner's comments "reflected a reaction to a simulator program that was not functioning properly, and that was still undergoing testing."

Lawmakers and regulators were troubled over the fact that they initially did not have access to these internal messages.

FAA said in a statement that when it became aware of the messages, the agency found them "disturbing" and said it was "disappointed that Boeing did not bring this document to [their] attention immediately upon its discovery."

DeFazio sent a letter to Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao, after the messages and emails were released, writing that the "messages indicate that Boeing withheld damning information from the FAA, which is highly disturbing."

“I would say deliberate concealment would be a criminal act,” DeFazio said in October, when Kerley asked him if he felt the concealment of information could lead to criminal charges for Boeing. “We can't say that it was deliberately concealed definitively at this point."

ABC News' Christine Theodorou and Michelle Stoddart contributed to this report.