Elizabeth Holmes on Theranos devices not working: 'I know that we made mistakes': 'The Dropout' episode 3

Watch the two-hour documentary, "The Dropout," THIS FRIDAY, March 15, 2019, at 9 p.m. on ABC.

This is episode 3 of "The Dropout," a six-episode ABC Radio podcast about the fall of Elizabeth Holmes' startup Theranos. If you haven’t listened to episodes 1 and 2, we advise that you do so first.

By 2013, just 10 years after Elizabeth Holmes had founded her blood-testing startup Theranos as a 19-year-old Stanford dropout, she had landed a major client and was well on her way to being a star of the biotech world.Between 2013 and 2015, over 40 Theranos Wellness Centers were built inside Walgreens stores in California and Arizona, attracting new investors and making Holmes a media darling.

Holmes hired Academy-Award winning filmmaker Errol Morris to create a series of promotional videos for Theranos.

“The kind of advertising I like doing is where you're creating a campaign, or an idea of a brand, where there's none that had existed before,” Morris said in a behind-the-scenes video that was a part of his Theranos advertisement campaign.

The advertisements were simple: Theranos customers were set against a stark white background, facing the camera, staring straight into the lens. Morris’ voice could be heard off-camera asking the customers questions about their experiences with blood tests and needles.

“I have a very bad relationship with needles,” one woman said in the advertisement.

“As soon as I sit I start to hyperventilate,” another woman said.

Morris then asked the customers about taking a blood test using just one drop of blood.

“Bring it on,” and “Wow, that’s it?” were some of the responses featured in the advertising video.

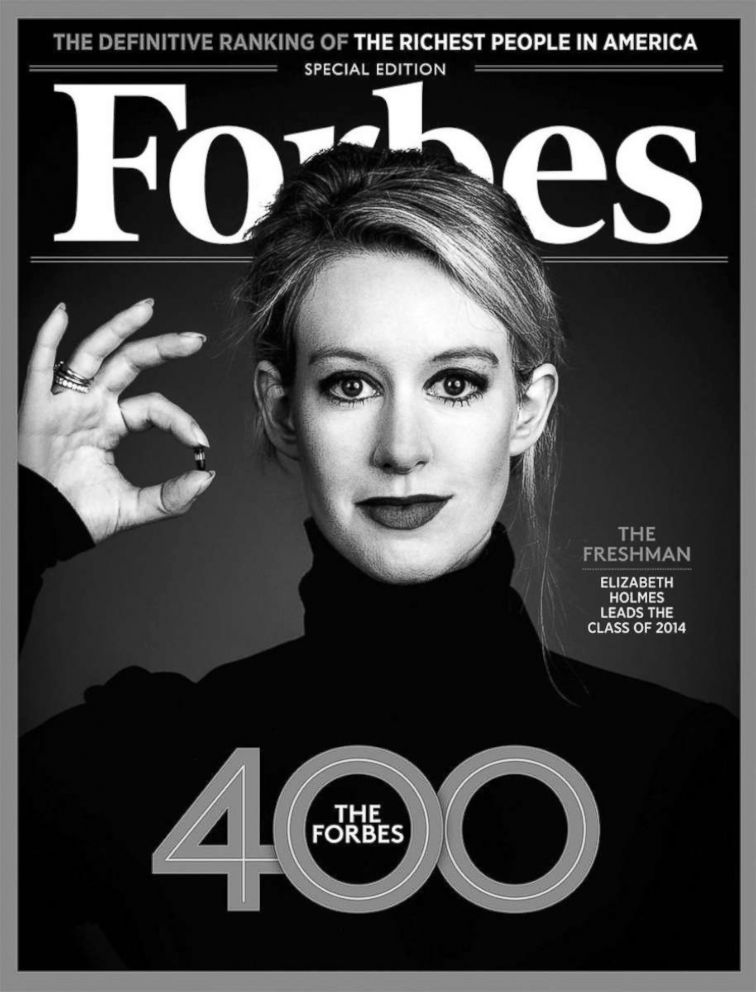

In one advertisement, Holmes’ serious face filled the screen in front of a white background. Her eyes were wide and unblinking. She was wearing a black turtleneck with her blonde hair pulled back.

“People don’t even know that they have a basic human right to get access to information about themselves and their own bodies,” Holmes said in the advertisement.

In more behind-the-scenes footage, Holmes was standing on the set, surrounded by cameras and equipment. Both she and Morris sounded genuinely giddy to be working together.

“I’m a fan,” Morris said to Holmes in the video.

“Likewise, likewise,” Holmes replied.

But it wasn’t just this famous documentarian who was a fan of Holmes and her grand vision. By 2014, her company was valued at nearly $10 billion, making her -- at least on paper -- the world’s youngest female self-made billionaire, worth a staggering $4.5 billion at the time, according to Forbes. By then, she had about 700 employees and plans to expand the Theranos Wellness Centers in Walgreens across the country.

The media was obsessed with the young Stanford dropout who was going to change the world and save people, one finger prick at a time. Holmes started showing up everywhere. She was honored at the 2015 Glamour Women of the Year Awards and introduced on stage by Oscar-winner Jared Leto. She spoke at Forbes' "30 under 30" and was featured on CNN, "CBS This Morning" and CNBC.

She graced the covers of countless magazines, including Fortune, Inc., Bloomberg BusinessWeek and Forbes, and was named one of Time Magazine’s “100 Most Influential People” of 2015. Wired Magazine called her work “mind-blowing” and there was even a glossy fashion spread in The New York Times Style Magazine.

That same year, former President Bill Clinton even interviewed her on stage at the Clinton Global Initiative.“Don't worry about the future, we're in good hands,” Clinton told the audience, gesturing at Holmes.

“These big splashy profiles were kind of big wet kisses,” Kara Swisher, editor-at-large for Recode magazine and a contributing writer for The New York Times, told ABC News’ Rebecca Jarvis for “The Dropout” podcast.

“Given how much money had been invested, given who was doing the investing, given her board, given her whole style and look, I mean it just it played into a lot of things that magazines like,” added Swisher.

Swisher remembered Holmes approaching her at a technology event and asking to be featured on stage at one of Recode’s events.

She said she remembered Holmes telling her, “You need more women on stage,” to which Swisher said she replied, “I know but not you.”

“I really remember thinking at that time, ‘I wonder if it works,’” Swisher told Jarvis.

Health care venture capitalist Ann Lamont, who has been named to Forbes’ coveted “Midas List of Top Tech Investors” multiple times and is one of the most successful women in her field, remembered an encounter with Holmes at a Forbes conference.

Lamont told Jarvis that she was about to speak on stage and went to the backstage green room to get her purse.

“Elizabeth Holmes was on before me, and I had left my purse in the green room ... and I could not get into the green room because she was there, and she had two bodyguards outside the green room, and two inside the green room,” Lamont said.

Lamont said she had to wait an hour before she was able to get her purse.

“I was like, ‘Who the hell is this woman?’” Lamont said.

Meanwhile, back at Stanford, the legend of Holmes was spreading. It was a time that Dr. Phyllis Gardner, a professor of medicine at Stanford, remembered well.

“I heard she was traveling with four bodyguards, carrying guns, packing heat, and traveled in a private jet. And she bragged about the bulletproof glass in her building, and I thought there was a lot of self-grandiosity involved,” Gardner told Jarvis on “The Dropout” podcast.

She said that students were “enamored of the story.”

“I think, particularly the women students, loved seeing a woman entrepreneur succeed. ... I mean, I understood that. I wanted to see a woman entrepreneur succeed,” Gardner said.

Adding to the momentum, then-Vice President Joe Biden visited Theranos’ Newark, California, facility on July 23, 2015.

After his visit, Biden called Theranos a “laboratory of the future” during a health care roundtable discussion, and added, “You can see what innovation is all about just walking through this facility.”

But one employee says there was a problem with the vice president’s visit.

“That was completely fake,” former Theranos chief design architect Ana Arriola told Jarvis.

According to friends who worked there at the time, Arriola said what Biden saw that day was completely rigged for his visit.

“They asked all the clinicians that were not full time to leave, don't show up for work that day ... Apparently, it was a video that was running on the machines, that they were not actually working devices at that period,” Arriola said.

A former employee and friend of Arriola’s, who says she was present that day, told Jarvis that she remembered the room filled with what was supposed to be Theranos’ breakthrough Edison devices was actually just a microbiology office days before, filled with old desks and computers.

This former employee said they kicked out the microbiology team, gave the room a fresh coat of paint and stocked it with every Edison they could find. In a photo of the room she took the morning of Biden’s visit, there are multiple Edison devices stacked, row after row with fans seen in the foreground. In an email, this employee wrote, “The fans in the doorway are because they had been trying to dissipate the new paint smell.”

But Biden was apparently none the wiser and, according to the former employee, said of his visit, “The president and I share your vision of the new health care paradigm, focused on preventative care.”

But noticeably absent from all of the gushing media attention over Holmes and Theranos was any detail into how the technology actually worked.

Instead, much of the press at that time had made note of Holmes' many eccentricities. In a 2014 Fortune article, for example, Holmes “admits -- laughing nervously at the eccentricity of it -- that after a meal she sometimes examines a drop of her own or others’ blood on a slide, and says she can observe the difference between when someone has eaten something healthy, like broccoli, and when he’s splurged on a cheeseburger.”

The article also quoted Channing Robertson, then a Theranos board member and Holmes’ former Stanford professor, who said once he heard about her idea for a new blood-testing system using a finger prick, he “realized I could have just as well been looking into the eyes of a Steve Jobs or a Bill Gates.”

The article also stated that Theranos offered “more than 200 of the most commonly ordered blood diagnostic tests, all without the need for a syringe,” but that “precisely how Theranos accomplishes all these amazing feats is a trade secret.”

It was an idea that Holmes was repeating everywhere she popped up and former Theranos employees who’d quit couldn’t believe what they were reading.

“I fully expected the company to last maybe two years before running out of money and goodwill and running into the ground. So it was completely shocking,” former Theranos employee Adam Vollmer told Jarvis on “The Dropout” podcast.

Vollmer said that once he and his friends and former Theranos colleagues Justin Maxwell and Mike Bauerly had all left the company, they watched from the sidelines as Holmes became a celebrity and they started to wonder if the company had actually turned things around.

“When the whole ... high-profile media blitz came around and I remember ... sort of following this moment, like, ‘Were we wrong?’ but at the same time knowing we weren't wrong,” Vollmer said. “We had this massive amount of skepticism.”

As Holmes and Theranos were getting more national attention, Vollmer said people started coming to him asking about jobs opportunities at Theranos and asking him for recommendations.

“I actively turned away at least a half a dozen people who were seeking jobs there,” Vollmer said.

Former Theranos board member Avie Tevanian, Apple’s former head of software who Holmes had recruited to her company, was also wondering what was happening. Tevanian had joined Theranos’ board in 2006, but resigned about a year later after he said Holmes rebuffed serious concerns he had raised with Theranos’ product and how the company was run as a whole.

“I'm reading the press [at this point], I'm seeing things pop up inside of Walgreens and I'm wondering, 'Maybe it finally works.' But I'm still, in my mind, remembering all these other things, and saying, ‘I still don't believe it. I still don't believe it,’” Tevanian told Jarvis on “The Dropout” podcast.

In reality, at the peak of Holmes’ fame in 2015, Theranos blood-testing machines could only run about a dozen tests and with only questionable accuracy, according to former employees. Just before Theranos launched its first Wellness Center at a Palo Alto Walgreens in September 2013, employees said the machines would often fail.

When questioned in a 2018 deposition for an investor lawsuit, former Theranos lab director Dr. Adam Rosendorff commented on Theranos technology, referring to as “the miniLab.”

“When you say the miniLab was not working, what do you mean?” an attorney asked Rosendorf in a deposition obtained by ABC News and featured on “The Dropout” podcast.

“It wasn't giving accurate results,” Rosendorff replied.

But the fact that the machines weren’t functioning didn’t seem to deter Holmes. In a 2017 deposition obtained by ABC News, an attorney for the Securities and Exchange Commission asked Holmes, “You're about three months away from going live ... in the patient setting? Did it concern you that a number of tests weren't working on Theranos' devices?"

“I know that we made mistakes,” Holmes replied. “But we were trying to take this forward and at that time thought that, thought that we were doing the right thing.”

Unbeknownst to the company’s investors and the public, Theranos was touting its “revolutionary technology” while using blood-testing machines from third-party manufacturers -- the same machines as its competitors -- for much of its testing.According to a Holmes' COO and partner Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani's 2017 SEC deposition, obtained by ABC News and featured on “The Dropout” podcast, Theranos first started buying machines from third-party manufacturers like Siemens in 2010 -- a few years before they launched their Wellness Centers inside of Walgreens.

Nevertheless, Holmes hired TBWA/Chiat/Day, one of the most exclusive advertising agencies in the country, to create an ad campaign for Theranos. Chiat/Day is known for creating iconic Apple campaigns like, “1984” and “Think Different,” and Holmes, ever Apple-obsessed, wanted them for her company.

“We were told of the story and her vision for Theranos and it was great. We thought something really special was going to happen. ... Could this be the next Apple?” Stan Fiorito, a former group account director and team lead for Chiat/Day, told Jarvis on “The Dropout” podcast.

Fiorito, along with his former colleague Mike Peditto, were on the Chiat/Day team assembled to work with Theranos’ ad campaign. Peditto was a management supervisor for the ad agency who was in charge of communications for promoting the Theranos-Walgreens partnership, among other things, while Fiorito, as the group’s account director, was in charge of all the financial and creative output for the agency. Balwani was Fiorito's main contact at Theranos.

For Chiat/Day’s first meeting with Theranos, the ad agency assembled a group of its most senior executives at their Los Angeles offices. Peditto said Holmes and Balwani flew in from Silicon Valley for the meeting on a private jet.“I remember seeing her through the glass and being like, 'Who is this person? What is this product?'” Peditto told Jarvis on “The Dropout” podcast. “The stature of everything felt very, like, a politician or like royalty was there like we were rolling out the red carpet.”

Like many before them, Fiorito said the Chiat/Day team was taken with the Theranos vision and felt Holmes had made a dramatic first impression.

“I mean the first thing, if you ever meet Elizabeth, that you'd notice is her voice. It's extraordinarily deep. It sounded to me like she was a man, or a robot, or both -- a man robot,” Fiorito said. “She carried herself like a highly educated, highly intelligent person, which she is. And you know, you're struck by her very measured way of talking and responding to you. And it did feel ... like a very well-polished politician.”

Theranos eventually inked a $6 million retainer with Chiat/Day, which later increased to a staggering $11 million agreement. And as the word spread around the agency about this secretive new client, everyone wanted to be a part of it.

“I think the vision of wanting to change the world, that was really attractive to the type of person that worked at Chiat. So a lot of people were raising their hands to work on it. ... This is the type of work that I've always wanted to do in my career,” Peditto said.

But according to Fiorito, it wasn’t long before things started getting weird. For example, he said Holmes would fall off the grid and “go dark for a month.”

“That is not typical” of most clients he’s worked with, he said, “not given the ambition and the desire to move quickly and then be completely unresponsive was odd very odd to us.”

Fiorito said the Chiat/Day team witnessed other strange behaviors as well. He remembered a time that they went to Palo Alto to meet with Holmes in order to get website script copy and retail materials approved.

“She didn't want to have that conversation and she was really excited about showing us these little crocheted finger puppets,” Fiorito said. “They were potentially for children after they got their finger prick, that they would give these away. And it was like talking to a 13-year-old girl, how excited she was that these things were made and they were going to give them away. ... And she talked in a different tone of voice. It was interesting.”

And Fiorito said Balwani made his job difficult. As Balwani’s main Chiat/Day contact, Fiorito said that whenever the team pressed Balwani for more information about Theranos’ product and technology, “he became almost angry that we'd even ask the question and that's what was really bizarre to us.”

Another issues they had with Theranos, Fiorito said, was their inability or reluctance to pay their bills on time.

“Did they not have the cash flow? Did they not understand why things cost what they did?” Fiorito said. “So that was where the tension was between Sunny and I, me trying to explain why your monthly bill was X.”

But despite their hang-ups with Theranos, the Chiat/Day team worked tirelessly on the creative elements for Therano’s campaign, which included the website design and promotional materials.

“They wanted to be in over 2,000 Walgreens stores in a really short time frame, which put a lot of pressure on ... the retail work, to get the retail work done,” Fiorito said.

As they were designing the look of Theranos’ website, Peditto said the project “had that gravitas that felt like this is something big.”

The work Chiat/Day created was designed to connect to viewers on an emotional level. One advertisement featured a child with big blue eyes and a quizzical look on his face with the words “Goodbye, Big, Bad Needle” in bold type.

“Everything was based on this tiny drop of blood,” Peditto said. “So we wanted to make that a big portion of the iconography of the brand. ... We want wanted to have really strong human portraits where you're really looking into their eyes.”

Before they could unveil the campaign to the public, Chiat/Day had to make sure every claim made by Theranos could actually be proven and it wasn’t an easy task. For example, Peditto said Theranos wanted to claim in its advertisements that customers would get results in four hours and that they could run hundreds of tests on one single drop of blood.

“We talked to them a lot about, ‘It has to be true at the time of publication or you can't do it. ... You have to be able to do it then, not in 10 years, not in five years, you have to be able to do it then,’” Peditto said.

But a lot of Theranos’ claims turned out to be what Chiat/Day called “puffery.” The agency said it was forced to amend a lot of the original copy Theranos wanted for the website and promotional materials, for example, “one single drop” became the more vague, “one tiny drop.”

At one point, Peditto said he inquired about the location of a Theranos lab the company said was in Arizona.

“I was curious where it was and I was told, ‘Oh we haven't built it yet.’ It's like, 'But you're doing the tests? How do you do the test then?'” he said.

Peditto said he was shocked when he learned that in actuality, Theranos was using FedEx to send the patient samples collected at the Arizona Theranos Wellness Centers to a lab in Palo Alto.

“We were blown away,” Fiorito added.

When Theranos first pitched Walgreens in 2010, one of the key selling points was that its breakthrough device could process tests right on site. But Peditto said he then realized Theranos wasn’t going to actually put these devices inside of Walgreens.

Putting their devices inside of store would require approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, something Theranos did not have. Instead, Theranos took advantage of a regulatory loophole in the law. They would put Theranos Wellness Centers inside of Walgreens but would ship all the blood samples to Theranos’ central lab for processing. This would let Theranos carry out the process without FDA approval.

“We didn't need FDA clearances,” Balwani said in his 2017 SEC deposition. “I think around the end of 2011 or early 2012, we said, 'What if we shipped samples and ship them to a central location? Yeah, it changes a few things in the model, but it allows us to launch faster.'”

Fiorito and Peditto said they started to question the existence of the top secret “revolutionary technology” and it wasn’t long before they were questioning the real identity of Theranos.

“I was at one point convinced it was a front for the government,” Fiorito said. “The reason why, is that one of the first meetings I had with [Holmes], she had said that the box had been field tested in Afghanistan, and ... you look who is sitting on the board and she would continue to drop major political and military names.”

He added, “It got to a point where like OK, maybe this whole thing is some sort of CIA and I'm kind of joking but I'm also not joking. I'm like, what's going on here?”

By 2015, the Theranos board of directors was a who’s who of government heavyweights. It included former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, President Donald Trump’s now-former Secretary of Defense, retired Gen. James Mattis, and George Shultz, who had served as President Richard Nixon’s Secretary of Treasury and President Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of State.

In a 2017 deposition from an investor lawsuit, obtained by ABC News and featured in “The Dropout” podcast, former Tennessee Sen. Bill Frist, who was also on Theranos’ board, said he remembered being “impressed with the technology,” Now-retired Adm. Gary Roughead, another board member, said in a deposition obtained by ABC News that he “just saw this potential that was there and was intrigued by that.”

Holmes met several of these men through Shultz -- all of whom were members of the Hoover Institution, a public political think tank, at Stanford University.

As many Theranos board members describe it, Shultz would set up a meeting and Holmes would join and charm. After one such meeting, Roughead said in his deposition that he saw big potential for deploying Theranos devices with the U.S. Navy.

“Many of the ships ... operate without any medical officers onboard and decisions are made ... with very limited diagnostic information regarding the welfare of the men and women who serve on the ships or submarines, and oftentimes missions are interrupted because of lack of good information,” Roughead said in his deposition. “And so for me being able to see the technology deployed would ... ultimately result in better care and more immediate care for people.”

Holmes’ board was an impressive roster of dignitaries. But some former Theranos employees, including senior software engineer Michael Craig, were perplexed.

“A friend of mine said your board looks like you guys are ready to take over the world, not start a medical device company,” Craig told Jarvis.

But investors loved it. According to attorney Reed Kathrein, a partner at Hagens Berman who sued Theranos on behalf of investors, the company’s impressive board of directors, along with the Walgreens partnership, was a major selling point.

“They all invested on the fact that you had this wonderful board of directors of outstanding individuals ... [and] by allowing their names to be out there. They all vouched for Elizabeth Holmes,” Kathrein said.

Kathrein has litigated hundreds of these types of suits and said that this one felt remarkably similar to another one from earlier in his career: Bernie Madoff, the former financier who’s now serving life in prison for running one of the biggest Ponzi schemes in U.S. history.

“I spent six hours in jail interviewing [Madoff] in South Carolina and really felt that I got to see a little bit of who he truly was. And I see that in Elizabeth Holmes and the way she operated. ... I think they're very similar people: smart, charming bullies,” Kathrein said.

Just like Madoff, Kathrein said Holmes used her expanding circle of VIP connections to build trust and attract money. When all was said and done, Holmes raised more than $1 billion dollars for her company. Her list of major investors included: the Walton Family, founders of Walmart, media mogul Rupert Murdoch, the DeVos family, which includes Trump’s Education Secretary Betsy DeVos.

Many of these people were connected to one another.

“The husbands of one of the Devos and one of the Walton family were on the same board together. The other investors were all in one way or another tied with the GOP or the Republican Party, which is the same as the people at the Hoover Institution. ... And so she was able to sell to all these people and get them because they all trust each other if you're doing it: 'It must be good and I'm sure you wouldn’t lie to me,'” Kathrein said.

But it wasn’t just the ultra-wealthy investing. Eileen Lepera, a retired executive assistant, living about 15 minutes from Theranos’ headquarters, said she heard that Theranos was going to be the next Apple and saw an investment opportunity.

She stretched and put $150,000 in the company.

“It was the biggest investment of my life,” Lepera told Jarvis on “The Dropout” podcast.

Lepera was hoping to buy a new house with the proceeds and was confident that Theranos would deliver.

“We were told it was cutting-edge technology,” she said. “I was trusting the knowledge and the expertise of who I bought it from.”

Lepera said she went to the Palo Alto Walgreens to test the alleged “cutting-edge technology.”

“It was their first beta test site,” she said. “And it was just a simple door that said Theranos. I went in and I sat in the little room. There was ... an aquarium, to, I guess, to calm you down and it was calming. ... I thought it was modest, but I didn't think it mattered. And so my experience was good and I felt OK.”

At one point, Lepera said she took $50,000 out of the original $150,000 investment, not because of any red flags, she says, she just needed it elsewhere. When she went in to fill out the paperwork to remove the $50,000, Lepera said she ran into Holmes and was “shocked” at how people seemed “almost afraid” of her.

Lepera, like most Theranos investors, would end up losing all the money she invested, but it took another two or three years for that to come to light.

“I'll never earn that much money back in my life,” she said. “I don't have enough years to earn and I'm retired. I don't want to go back to work. So it's a hard pill to swallow.”

By 2015, Theranos was in about 40 Walgreens stores in California and Arizona and now people weren’t just investing their money, they were now potentially putting their lives on the line as they turned to Theranos’ technology for blood tests that they were promised would test for hundreds of diseases, everything from cholesterol to cancer.

Sheri Ackert is a 62-year-old breast cancer survivor who has to have her blood drawn regularly while she’s in remission to ensure she’s still healthy. She said she learned about Theranos’ finger prick tests through her OBGYN and thought it might be a nice alternative to an intravenous blood draw.

So she went to a Phoenix Walgreens to try it out and said the experience was pleasant.

“I went in, immediately get seated, there were two people, they were awesome, they seemed to know what they were doing,” Ackert told Jarvis on “The Dropout” podcast.

But when the results came back, her heart sank.

“I saw that the estrogen amount was over 300. ... The first thing that came to mind was, ‘Oh my god, [my cancer] is recurring’” Ackert said.

She called her oncologist’s office.

“The nurse called me back and she said, ‘I’m so sorry that’s not good. ... If you’ve got an estrogen level of a 35-year-old there could be a tumor growing somewhere,’” Ackert said. “I will never forget that day.”

Ackert said her doctor told her to go in for more for tests, but this time recommended a non-Theranos lab.

“It was about a week later, I got the call from my doctor and he said, ‘Congratulations your estrogen is basically nonexistent,’” she said, which for a breast cancer survivor was good news.

It turned out that the Theranos test had been off by hundreds of points. There was no tumor. No new cancer. Ackert said she tried to reach out to Theranos for answers but got no response.

“No one from Theranos ever called me to apologize, no one,” she said. “And in my opinion, that’s the least you can do when you mess up so badly with someone who potentially has a cancer recurrence and they’re worried, stressed out, and you ignore it -- you just totally ignore it ... not OK.”

Ackert was far from alone. Around the same time, one state over, there was Pallav Sharda, a physician turned entrepreneur. After learning about the exciting new startup, he visited the Palo Alto Theranos Wellness Center in Walgreens.

“The first thing I noticed was the phlebotomist who was taking my blood, I asked her, 'Well, wait. Wait a minute. This is supposed to be a pinprick.' ... But she was doing a test tube draw in the usual way. She put a tourniquet on, and she took the test tube out,” Sharda told Jarvis on “The Dropout” podcast.

Sharda said the phlebotomist told them that some of the tests have to be done the traditional way, with an intravenous blood draw. He had chosen Theranos for the pinprick test, but let it go and still opted to get the test.

“It was a little red flag. I was, like, ‘Well, that's false marketing,’” he said.

A few days later, Sharda’s doctor called with an upsetting diagnosis. He said the Theranos results had indicated that he was prediabetic. As someone who comes from a family history of diabetes, he said he had been working to stay out of that range for years and the news was devastating.

Sharda said his doctor recommended he start medication, but first he decided to retake the same blood tests at a different lab. Sharda was relieved when he said the new results put him safely outside the prediabetic range.

“I'm probably the safest error that Theranos made. ... I was taking care of myself,” Sharda said. “But I'm sure there were thousands of medical decisions made on Theranos lab results which put serious medicines in people's pill packs for them to take without anybody double checking what that number was, on the basis of which that decision was made.”

While Sharda and Ackert were getting their test results, back in Los Angeles, Mike Peditto and Stan Fiorito of Chiat/Day had long since moved on from Theranos. They said that Theranos suddenly ended their relationship with the ad agency out of nowhere. The Chiat/Day team was frankly relieved but Peditto said he still couldn’t shake the feeling that there was something seriously wrong going on at Theranos.

“I thought at some point something will happen that's going to expose this,” he said. “I mean you didn't know how deep it was or who that person was going to be. ... I literally would Google ‘Theranos scam’ wondering when that information was going to come out.”

Peditto said he still worries that Holmes and Theranos might retaliate against naysayers like him.

“I've got to be honest, even talking to you guys now. There's still a part of me that has fear. Are we being set up? Are there going to be cops that come in and arrest [me] [or] lawyers that come through? Just because they were, just very unscrupulous when it came to just defending and protecting and make sure nobody talked,” he said.

Holmes and her counsel, Balwani and Errol Morris did not respond or declined ABC News' requests for comment for "The Dropout" podcast.

"The Dropout" is a six-part series on the rise and fall of former Silicon Valley darling Elizabeth Holmes and her company Theranos. It is written and produced by ABC News' Rebecca Jarvis, Taylor Dunn and Victoria Thompson. Listen to "The Dropout" for free on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, iHeartRadio, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn, the ABC News app, or your favorite podcast player.