What is the Electoral Count Act and why does it present problems?

With voting rights legislation all but dead in the Senate, and the former president now openly suggesting he tried to use a vaguely-worded 19th-century law to try to manipulate the last presidential election, a growing group of bipartisan lawmakers is backing the idea of changing how Congress tallies presidential election results by reforming the 1887 Electoral Count Act.

The law was intended to set up a peaceful transfer of power after an election dispute, but it's one former President Donald Trump and his allies sought to exploit in a scheme to overturn the 2020 election.

Trump made his clearest statement yet this week that he believed Pence could and should have simply overturned the results himself, responding to Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, who was asked about efforts to reform the law on ABC's "This Week With George Stephanopoulos."

He said, "...how come the Democrats and RINO Republicans, like Wacky Susan Collins, are desperately trying to pass legislation that will not allow the Vice President to change the results of the election?"

"Actually, what they are saying, is that Mike Pence did have the right to change the outcome, and they now want to take that right away. Unfortunately, he didn't exercise that power. He could have overturned the Election!" Trump falsely claimed in a statement late Sunday.

By pressing then-Vice President Mike Pence to interfere with the ceremonial counting of electoral votes on Jan. 6, as well as outlining how states could -- and several would -- send conflicting slates of electors to Congress, and urging lawmakers to object to results, to which 147 Republicans followed, Trump took advantage of ambiguities in the law's language.

Republican leaders have signaled an openness to amending the text, but Democrats argue the effort, while potentially bipartisan, does not address what they call state voter suppression tactics they say will be felt in the midterms and could be a distraction from larger voting reform.

Addressing reforms to the law, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said the White House has "been open to and a part of conversations about the Electoral Count Act," but that it shouldn't be a "replacement" for larger voting reforms. She also called attention to Trump's statement as representing a "unique and existential threat to our democracy."

Some scholars warn that if lawmakers don't join together to reform the process, it will be weaponized again.

"There's enough focus now on the ambiguities of this statute that if it isn't Donald Trump in 2024, you could easily imagine a number of other actors taking a page from his playbook," Rebecca Green, co-director of the election law program at William and Mary Law School, told ABC News. "But the ECA is not just specific to one presidential election or one person. It's just become a more apparent problem to address after Jan 6."

Here's a look at the Electoral Count Act and why people are calling for it to be reformed:

What is the Electoral Count Act?

The Electoral Count Act is the law that governs how Congress counts electoral votes following a presidential election.

It essentially sets up a timetable for when different parts of the counting process must take place and sets up a dispute resolution process for how Congress will resolve irregularities in accepting electoral slates from states.

How did the law come about?

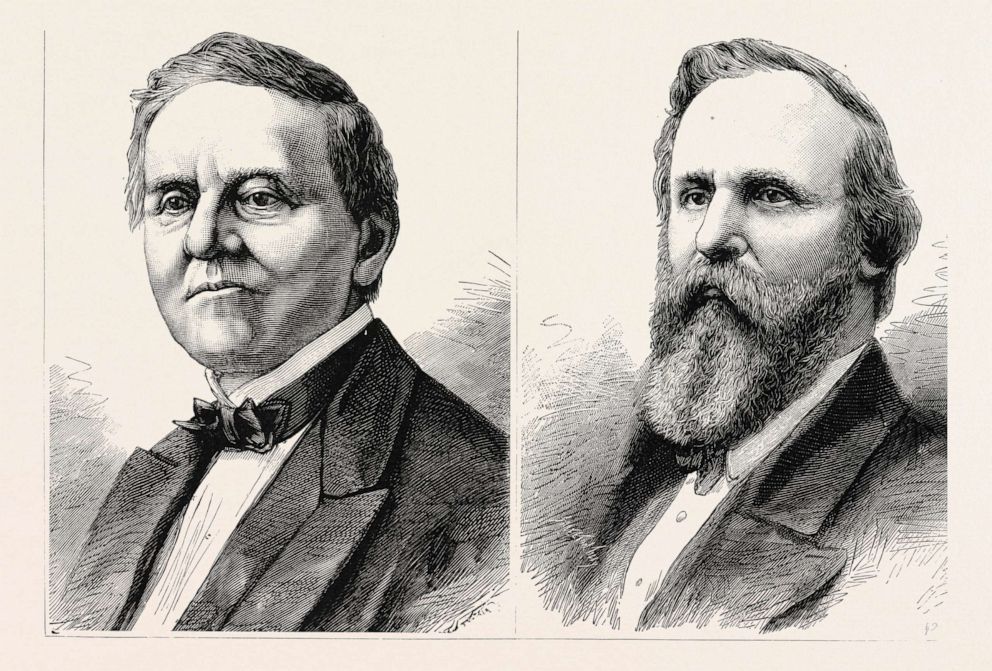

The law was crafted in response to a contested presidential election in 1876, when several states under the control of Reconstruction governments sent multiple slates of electors to Congress post-Civil War.

Samuel Tilden, a Democrat, had won the popular vote, but after Congress created an ad hoc commission to deal with the dispute, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was ultimately declared the winner.

Democrats refused to accept the results until the Compromise of 1877, which called for an end to Reconstruction and the withdrawal of federal troops from former Confederate states. A decade later, Congress passed a law that lawmakers hoped would prevent a future process from being upended.

But it has presented problems.

What problems does it present?

While there are several proposals for ways to reform the law, such as changing the timeline for "safe harbor" status -- when electoral votes are considered "conclusive" -- or resolving questions around judicial review following election disputes, there are two glaring areas that Green told ABC News lawmakers need to address.

The role of the vice president is unclear

The vice president's role in what usually is a ministerial proceeding -- simply counting and announcing the votes -- is extremely unclear.

The Constitution dictates that the president of the Senate, or the vice president, open the certificates of electoral votes from each state. Additionally, under the current Electoral Count Act, the president of the Senate carries over the proceedings and calls for objections.

The act says, in long, convoluted language, the each state's slates or "all such returns and papers shall be opened by him" -- the vice president, or president of the Senate -- "in the presence of the two houses when met as aforesaid, and read by the tellers, and all such returns and papers shall thereupon be submitted to the judgment and decision…"

"Does this run-on sentence mean that Mike Pence shall open only the ballots that he wants? Or does he have to open if there's more than one slate from a state -- how does he know which ones to open?" Green posed. "None of those questions are answered by the face of the statute."

She added, "Those vagaries produced the mischief that we saw in the 2020 election," she added.

ABC News Senior Washington Correspondent Jonathan Karl reported in his book "Betrayal: The Final Act of the Trump Show" that then-White House chief of staff Mark Meadows emailed to Pence's top aide a detailed plan penned by Trump's campaign lawyer Jenna Ellis outlining how Pence was to send back the electoral votes from six battleground states that Trump falsely claimed he had won.

Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward and Robert Costa also revealed in their book, "Peril," a memo written by John Eastman, whom Trump introduced at the Jan. 6 rally as "one of the most brilliant lawyers in the country," outlined another plan for how Pence would hand the election back to Trump on Jan. 6.

According to their reporting, Eastman instructed Pence to say, at the conclusion of counting, "because of the ongoing disputes in the 7 States, there are no electors that can be deemed validly appointed in those States." Then, Pence "gavels President Trump as reelected."

Pence would have declared the seven states that submitted the alternate slates of electors as being in dispute, and ultimately hand the election to Trump in the alleged plot. However, Pence rejected the pressure to do so, sticking to his strictly ceremonial role, and the National Archives never accepted the uncertified documents for congressional counting.

Despite all the manipulation, scholars argue it isn't reasonable to suggest the vice president would have been granted such interference.

"There has never been the kind of pressure that Mike Pence experienced on Jan. 6, 2021, before," Green said, "but it would be extremely illogical for the system to instill that much power in sitting vice presidents, particularly since sitting vice presidents are so regularly on the presidential ballot."

Additionally, the Justice Department and lawmakers on the House select committee investigating Jan. 6 are looking into those individuals who falsely signed on as alternate electors to declare Trump the winner in states he actually lost to Biden.

It's 'too easy' for lawmakers to object to a state's slate.

The law allows one congressman paired with one senator to object to the results submitted by each state -- which last year, made way for a long, drawn-out process as Republican after Republican, including several freshmen, contested results. Eight senators and 139 representatives, all Republicans, voted to sustain one or both objections to electoral votes in Arizona and Pennsylvania.

If a congressman finds a senator to join in their objection, both the House and Senate chambers are forced back to their chambers for two hours of debate and a vote, which some argue is an invitation for political grandstanding.

The objection tool was used only once in its first 100 years. In all three recent cases, the attempts have failed.

In 2001 and 2017, no senator would join with a representative to object. (Biden, then serving as vice president, was the one to gavel out a handful of Democrats' challenging Trump's electors.) In 2005, a representative and a senator objected to counting Ohio's electoral votes cast for George W. Bush, but the challenge was not successful.

Some lawmakers are now coalescing around the idea of raising the threshold for objections beyond just a single senator and representative -- or to creating a list of valid ground for objecting results.

One proposal raises that at least one-third of each chamber would be needed for an objection to be heard -- or more than 30 senators and 140 House members.

"The idea is that the current process is too easy and that perhaps it should be made a little bit harder to object, so that there's more consensus required and a couple of people can't kind of gum up the works as easily," Green said.

Collins, who is leading discussions with a group of 16 senators to reform the law, said she's hopeful it can be done on an "overwhelming" bipartisan basis.

"I'm hopeful that we can come up with a bipartisan bill that will make very clear that the vice president's role is simply ministerial, that he has no ability to halt the count, and that we'll raise the threshold from one House member, one senator, for triggering a challenge to a vote count submitted by the states," she told ABC's "This Week With George Stephanopoulos." "This is no small thing. I think it is really important that we do this reform."

Why act now?

Earlier this month, a Democratic-led committee released a 31-page report on potential reforms to the Electoral Count Act.

"As the events leading up to the violent attack on the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021, demonstrated, the Electoral Count Act of 1887 is in dire need of reform. It is antiquated, incomplete, vague, and open to exploitation," Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif., chairperson of the Committee on House Administration. "But to be clear -- reforming the Electoral Count Act, necessary as it is, would not restrain the erosion of democracy or the dishonest efforts across the nation to diminish and impede the equal freedom to vote."

Key Republicans including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell have expressed a willingness to back reforms, but Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has argued the reforms don't go far enough in addressing threats to democracy and restrictions to the vote in elections beyond the race for president.

As the movement gains new bipartisan traction, election experts are calling for lawmakers to keep the momentum up.

"If these disputes aren't resolved, then partisan actors are going to act a certain way and try to exploit ambiguities to their favor whereas if you sort of close those gaps prior to the election, then you're more likely to have a fair process that produces an outcome without dispute that it's legitimate," Green said.

She added, "We only have until 2024 to fix this."