Echoes of Trump's Controversial Central Park Jogger Letter Linger in Campaign Rhetoric

— -- Announcing his presidential campaign last year in the lobby of his flagship New York building, Donald Trump issued a dire warning about Mexican immigrants, painting them as murderers and rapists undermining safety in the U.S.

Since then, he has consistently mentioned uncontrolled immigration as one of the biggest threats to the American way of life — from refugees who may be terrorists and resources to border crossers who siphon jobs from Americans.

Nearly three decades earlier, Trump made a similar pitch to New Yorkers, warning of roving bands of muggers and murderers threatening to undo the fabric of his hometown.

The remarks came some 27 years apart but provide insight into Trump's willingness to paint groups with broad brushstrokes, convey danger in the unknown and strike an alarmist tone.

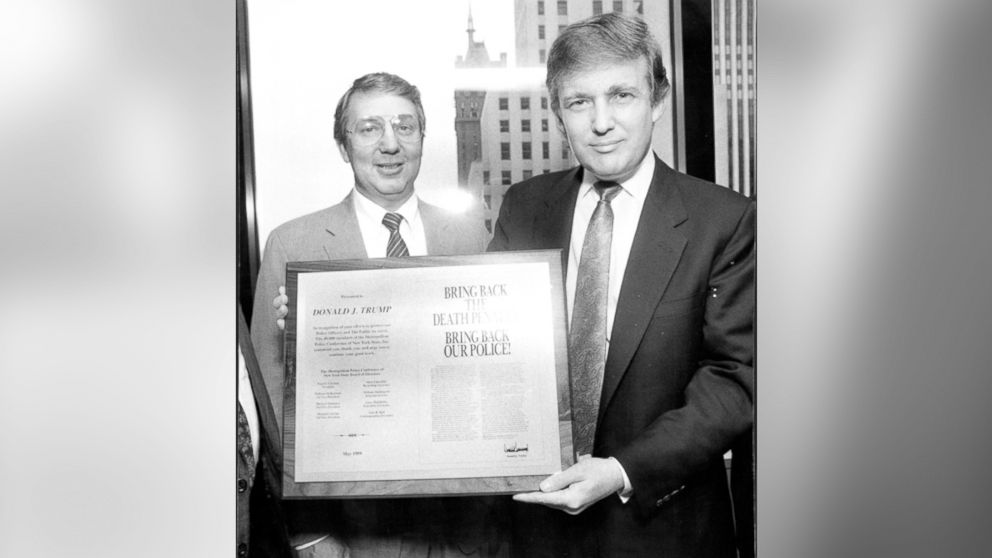

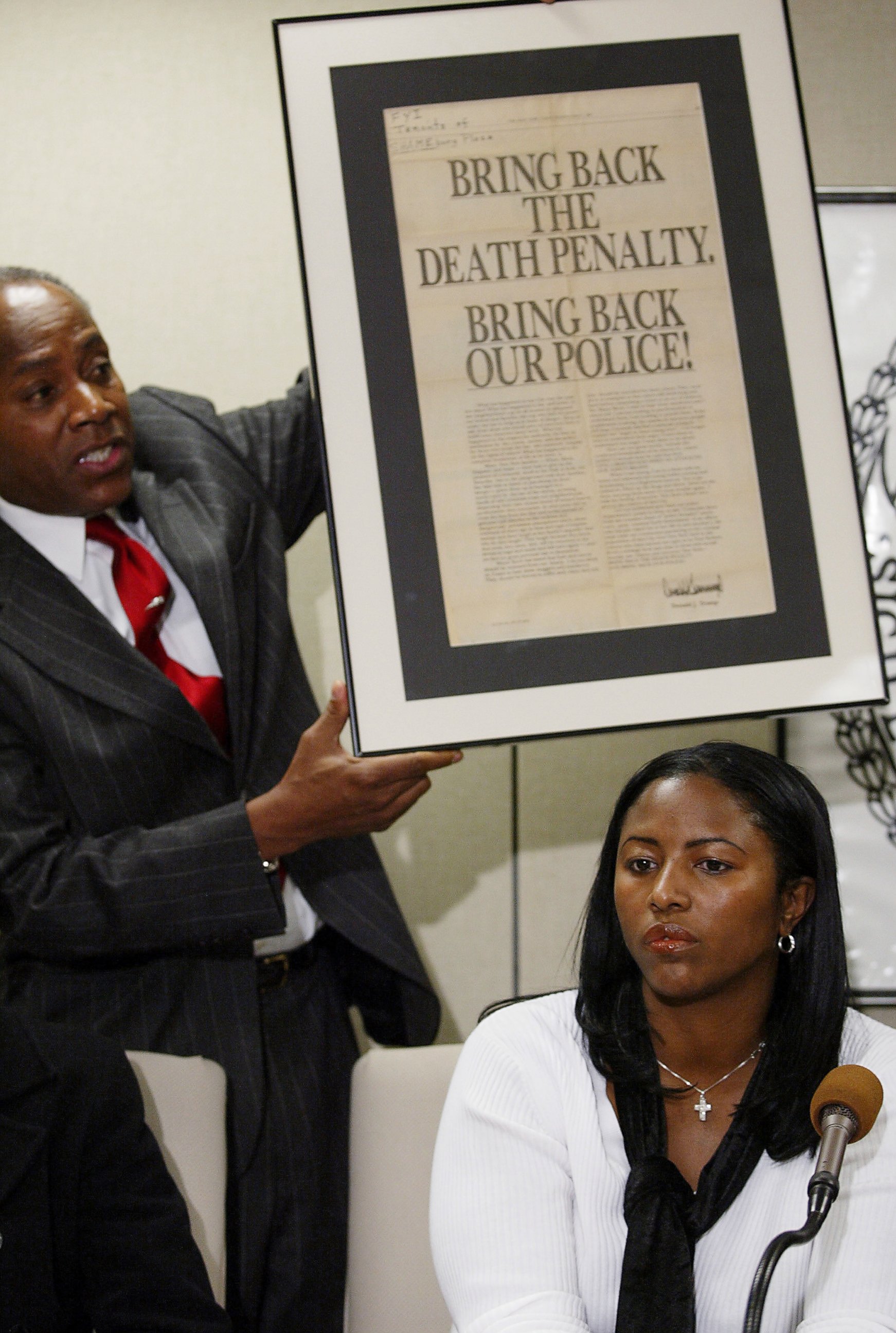

Trump's warning to New York City came in the form of an open letter published on May 1, 1989, during the Central Park jogger case, in which five male teens were accused of brutally attacking a white woman. The letter has gained renewed prominence in light of Trump's recent pitch to African-American voters amid poor poll numbers with the group.

The letter, with its blaring call to bring back the death penalty in New York, was controversial because of what some said were racial overtones. It came days after the brutal attack, when the 28-year-old investment banker victim was still lying in a coma and police were pressing forward with their case against the one Hispanic and four black teens.

The victim, who was at first was expected to die from her injuries, regained consciousness right around the time the letter was published. She was not able to remember any details about the attack, according to media reports from the time, and therefore was unable to identify any suspect.

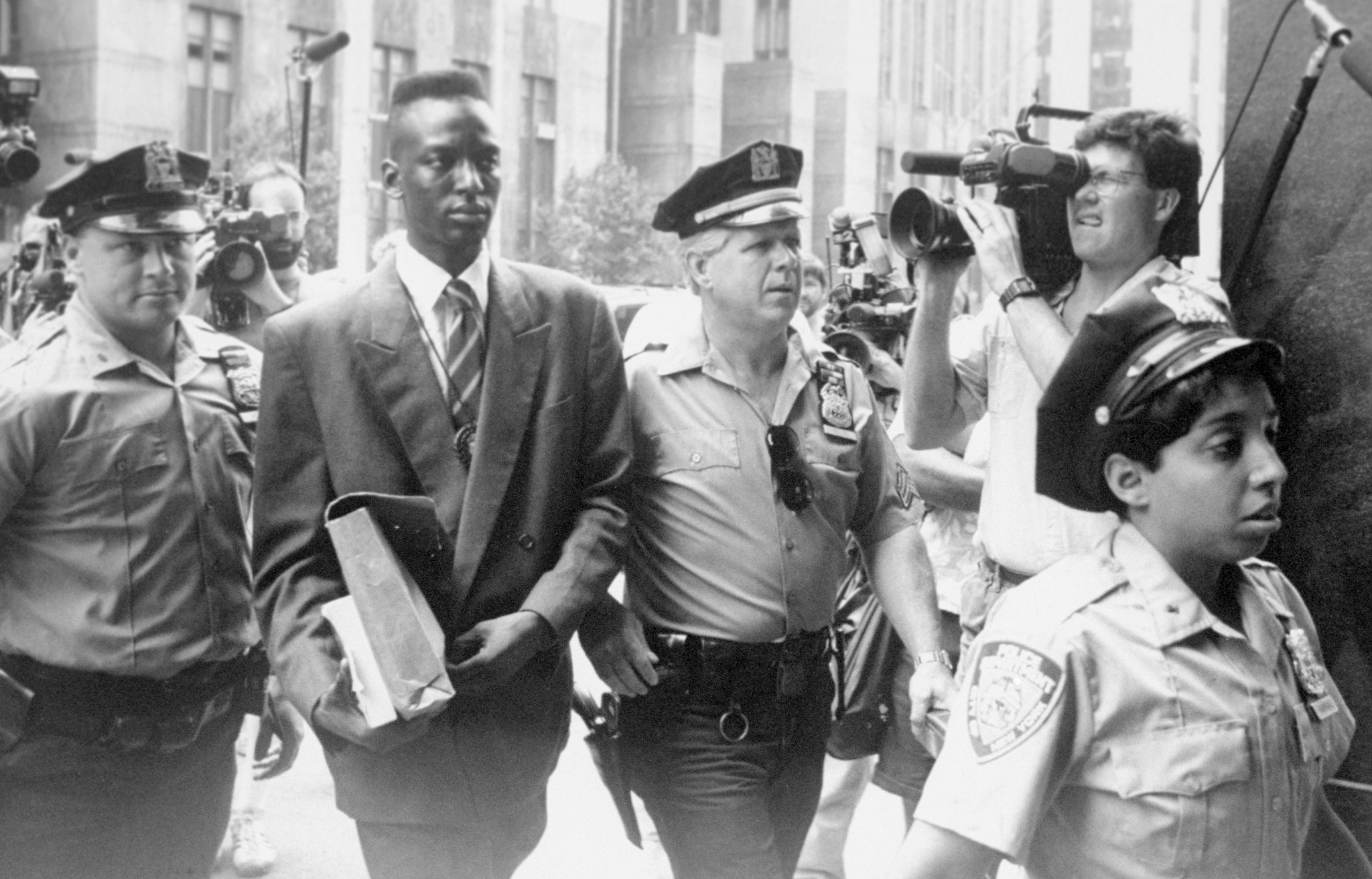

All five of the accused made various confessions, which later came under review, and were convicted on differing combinations of charges — including rape, robbery, attempted murder, assault and riot — and served time.

In 2002, the five were exonerated after an investigation by the Manhattan district attorney's office, The New York Times said. Another man confessed to the crime.

"Had Donald Trump had his way ... we would have been dead," Yusef Salaam, one of the exonerated men, told ABC News recently.

"They would have found out 13 years later that we didn't do it, but we would've been ghosts. We would have been speaking out, but it would have been from the afterlife," he said.

As recently as 2014, Trump continued to cast aspersions on the former suspects, saying in a New York Daily News op-ed, "These young men do not exactly have the pasts of angels."

Entering the Fray

To put the events in context: The attack in Central Park took place when Ed Koch was the mayor and George H.W. Bush was three months into his presidency. The city's crime rate was the highest it had been in more than a decade, according to FBI and NYPD figures from the time.

Trump was 42 years old, was married to his first wife, Ivana Trump, and had become a well-known real estate personality in New York. While his father's housing projects were in the boroughs, Donald Trump had turned his attention toward Manhattan, specifically midtown, and construction of Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue and a massive housing complex on the West Side.

The Central Park attack held the city's collective attention, with wall-to-wall media coverage that referred to the assault as a wilding and the suspects as a wolf pack — terms that were later criticized.

Then Trump decided to get involved. He penned the open letter to the city, calling for the reinstatement of the death penalty in connection to the case and painting a stark picture of life in the city amid a diminished police force and roving bands of criminals.

The letter, published in ads in four area papers — The New York Times, The Daily News, The New York Post and New York Newsday — was signed by Trump.

"What happened to our city, over the past 10 years? What has happened to law and order, to the neighborhood cop we all trusted to safeguard our homes and families, the cop who had the power under the law to help us in times of danger, fulfill some distorted inner need. What has happened to the respect for authority, the fear of retribution by the courts, society and the police for those who break the law, who wantonly trespass on the right of others? What has happened is the complete breakdown of life as we know it," the first paragraph of the ad read.

He said that New Yorkers of all races had become "hostages to a world ruled by the law of the streets, as roving bands of wild criminals roam our neighborhoods." He wrote that a permissive atmosphere had been created that "allows criminals of every age to beat and rape a helpless woman and then laugh at her family's anguish."

He then said he wanted to "hate these muggers and murderers" and "they should be forced to suffer and, when they kill, they should be executed for their crimes."

When asked to comment for this story, a spokeswoman for the Trump campaign pointed to his responses in a New York Times interview last year about his use of what some have called racially charged language.

He told the Times that he had no regrets about the 1989 letter but said that since the victim ended up surviving the attack, the death penalty would not have been the appropriate punishment. He denied that the letter was racially charged.

"This had nothing to do with race," he said about the ads, according to the Times. "I have always been a big believer, and continue to be, of the death penalty for horrendous crime."

The attack and its aftermath were already closely followed by the media, but Trump's letter brought in a different element, according to at least one of the accused teens.

Salaam, who was 15 at the time of the attack, was charged with rape and robbery and served nearly seven years in prison. He and the other four teens had their sentences vacated in 2002 after another man, Matias Reyes, admitted he was the sole person who attacked the jogger. The statute of limitations had expired by the time Reyes made his confession, and the city reportedly reached a $40 million settlement with the original five suspects, according to The Associated Press.

Looking back, Salaam considers the ads "the nail in the coffin — the fire starter, of sorts."

"[Trump] is also directly responsible in many ways for us being convicted. That's how deep this thing goes," Salaam said.

Reflecting on Trump's Role in the Case

Dr. Ben Carson, one of Trump's best-known African-American surrogates, feels that there is nothing wrong or concerning about the ads, going so far as to say that they fit with Trump's self-appointed title as the "law-and-order candidate."

"Obviously, it's hard to know," Carson said when asked what he thought Trump's intention was at the time, "but I do recognize that at that time, New York was in the middle of a crime spree. There was a lot of violence going on."

"It was really much more of a law-and-order push that was going on, and there was a lot of people that were talking about that at the time," Carson said. "One of the problems that happens when you look back at 20, 30 years is that it gets very distorted.

"I can tell you right around the same time as this story, when he moved to Palm Beach, he was the driving force behind removing restrictions against Jews and blacks from getting into clubs," Carson said.

Trump has made a similar argument, saying on "Good Morning America" in March that "there's been nobody that's done so much for equality as I have," citing his effort to equalize admissions to private clubs like Mar-a-Lago, which he owns, as an example.

Making an Impression on the Suspects' Advocates

The Rev. Al Sharpton was "intricately involved" in the case at the time, he said, and helped raise bail money for some of the accused teens.

Though Sharpton and Trump are two prominent New York personalities, they did not know each other personally in 1989, Sharpton said.

"That was our first impressions of him — that he was one that would do whatever that he felt he wanted to do to stoke the fires," Sharpton said.

The decision to take out the ads on the subject — The New York Times reported they cost $85,000 at the time — also came as a shock.

"It was unprecedented," Sharpton said. "You've got to remember that Donald Trump was a well-known local to regional business figure … who had not taken out full page ads on any social issue."

Delores Jones-Brown, a professor in the department of law and political science at John Jay College, said that the ads introduced Trump to some members of the public, including her.

"I remember thinking, 'Who is this guy, and why is he doing this?'" she told ABC News.

"I knew him for the developer investor millionaire that he was, but prior to the ad, I didn't see him as a racist developer investor," she said.

Trump has said that he is the "least racist person."

Appeal to Black Voters

In recent weeks, Trump has been very public in his appeal to black voters, telling a largely white crowd in Michigan in August, "What the hell do [black people] have to lose?" by voting for him. The appeals continue, and this past weekend he made his first trip to a black church in Detroit, accompanied by Carson.

The recent actions don't erase the past, however, and Trump's poll numbers among African-Americans have been among the lowest in recent history for any presidential candidate. Sharpton said "the facts don't speak to" Trump's being genuine about his appeal to black voters.

"I think that the appeal is based on the assumption that black people are stupid," Sharpton said.

As for Salaam, he isn't holding his breath for an apology from Trump. And when asked which presidential candidate would get his vote in November, Salaam laughed.

"It ain't gonna be Donald Trump!" he said.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the attack occurred during Ronald Reagan's second term, but it was actually during George H.W. Bush's presidency. The article has been updated.