New details on CDC's Provincetown investigation portray delta variant as serious threat

Adding more insight into the CDC’s updated mask guidance, newly published details of the Provincetown outbreak raise concern that the now-dominant delta variant may be able to spread among fully vaccinated people.

Following multiple large gatherings in Provincetown, Massachusetts, from July 3-17, investigators identified 469 COVID-19 cases, two-thirds of which were in fully vaccinated people. The delta variant was responsible for 90% of those cases. The breakthrough infections were among people vaccinated with Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson. None of the vaccinated people died, but most had some symptoms.

During the outbreak investigation, researchers learned that the amount of virus in the noses of vaccinated people experiencing a breakthrough infection was the same as in an unvaccinated person -- a worrying sign vaccinated people can spread the virus.

"This finding is concerning and was a pivotal discovery leading to CDC’s updated mask recommendation," said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky in a statement.

"This is a very concerning outbreak -- pretty much a 'super spreader event,'" said Dr. Carlos Del Rio, executive associate dean and global health expert at the Emory School of Medicine.

Experts caution that more studies are needed to understand if what happened in Provincetown holds up in subsequent outbreak investigations. The CDC report noted the social gatherings were "densely packed." And breakthrough infections are still relatively uncommon, with the majority of cases driven by spread among unvaccinated people. Meanwhile, an internal CDC briefing first published by the Washington Post and confirmed by ABC News outlined additional new data suggesting that the delta variant is different from prior variants in other ways. Chiefly, this variant appears to be extraordinarily contagious -- possibly more so than Ebola, Spanish flu, chickenpox and the common cold. It's also possible delta leads to more severe illness, but for now this is only a possibility and not firmly established.

Taken collectively, these new revelations prompted the CDC to update its mask guidance Tuesday to recommend that vaccinated people once again don masks indoors, especially in high-transmission areas. And that includes schools this fall.

"The rules have changed," said Dr. Dan Barouch, director of the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. "We have a different epidemic now that we did in May."

Throughout the spring and summer, the CDC based its guidance on scientific studies of prior COVID-19 variants, including the then-dominant alpha variant, which was first identified in the U.K. and swept the United States during the 2020-2021 winter surge.

But the delta variant -- which only just surpassed alpha as the dominant variant on July 6 -- is different. It hit the U.S. so fast that only in the past few weeks has sufficient data emerged to show scientists just how significant those differences were.

That means that throughout the summer, the nation’s public health guidance may have been based on alpha variant rules while the nation was living in a delta variant world.

It's a game of catch-up that's all-too-familiar to doctors and scientists who have dedicated their lives to preventing infectious disease.

"This is what I always say in a pandemic: I wish I knew today what I’m going to learn tomorrow," Del Rio said.

"When we released our school guidance on July 9, we had less delta variant in the country, we had fewer cases in the country,” said Walensky, speaking at a Tuesday press conference. "And importantly, we were really hopeful that we would have more people vaccinated, especially in the demographic between 12 to 17 years old," she said.

Now, Del Rio said, new data is telling us "that the virus has changed -- it’s a lot more transmissible, and it has been able to adapt."

Although it now seems that vaccinated people can pass the virus, "the great majority of transmissions is still coming from unvaccinated people," Del Rio said. "That’s why you’re seeing mandates come left and right. People are saying, enough is enough."

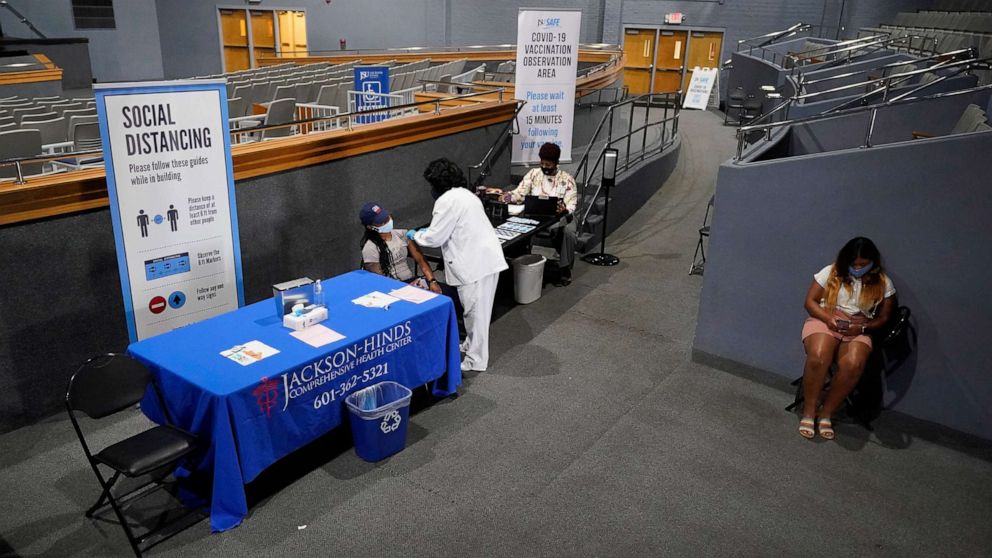

Experts say this is still a pandemic largely of the unvaccinated, with a majority of cases among unvaccinated people, meaning it's more important than ever for anyone who is not vaccinated to get vaccinated.

Crucially, current vaccines appear to work just as well against delta to dramatically reduce the risk of severe illness and death. But they may not work as well at preventing mild infections.

"Current vaccines continue to provide strong protection against severe illness and death, but the delta variant is likely responsible for increased numbers of breakthrough infections -- breakthroughs that could be as infectious as unvaccinated cases," said John Brownstein, Ph.D., the chief innovation officer at Boston Children's Hospital and an ABC News contributor.

The CDC brief said one of the agency's biggest challenges moving forward is countering the public perception that vaccines don't work. But the fact that roughly half the nation is already vaccinated likely saved the United States from an even deadlier summer surge, experts agreed.

"If it were not for the vaccines, there likely would have been a massive overwhelming surge in this county," Barouch said.

Even still, large portions of the country -- including children -- remain unvaccinated. And what scientists are learning about the delta variant’s capacity to transmit between vaccinated people might mean we need to mask up again -- especially in those high transmission areas.

"We have to get the unvaccinated vaccinated. And in the meantime, masking is useful, but not sufficient so we have to also add testing to the mix of mitigation strategies," Del Rio said.

For now, the future remains uncertain. Many scientists worry about a winter surge, while others feel encouraged that the delta variant might fade away as suddenly as it arrived.

"There is some evidence -- first from India and now from the U.K. -- that the delta variant surges and then begins to dissolve,” Barouch said. "We don’t fully understand why the sparks catch fire, and we don’t fully understand why the flames go out."

ABC News' Sasha Pezenik, Anne Flaherty, Arielle Mitropoulos and Eric Strauss contributed to this report.