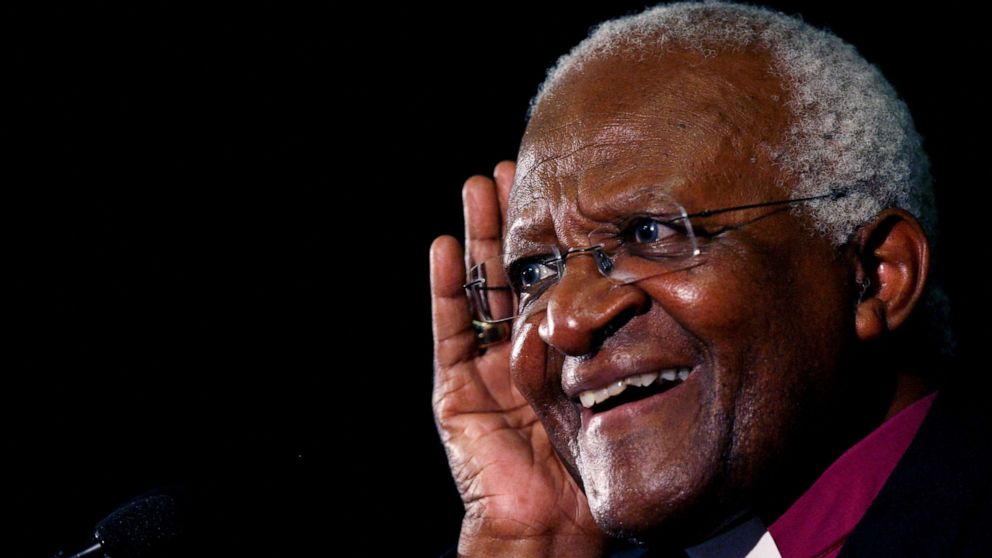

Desmond Tutu, South Africa's archbishop and Nobel laureate, dies at 90

LONDON -- South Africa's Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, an anti-apartheid activist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, died on Sunday. He was 90.

"The passing of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu is another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa," Cyril Ramaphosa, South Africa's president, said in a statement.

Tutu, a crusader for equality and racial justice, died in Cape Town, South Africa, the president's office said.

He rose to global prominence as a leader of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, struggling against a political and social system of minority rule that he saw as cruel and unjust. Amid a violent and turbulent time, Tutu was known for his sermons calling for non-violent action. He was awarded The Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

"Tutu was saluted by the Nobel Committee for his clear views and his fearless stance, characteristics which had made him a unifying symbol for all African freedom fighters. Attention was once again directed at the nonviolent path to liberation," according to the prize committee.

After apartheid ended in 1994, Tutu chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a body whose daunting mandate called for investigating the country's history of oppression, applying justice where necessary and helping the entire population step as one into a brighter future.

Under Tutu, the commission sought a middle ground between launching courtroom trials for "all perpetrators of gross violations of human rights" and total amnesty for them, Tutu wrote in a memoir, "No Future Without Forgiveness," published in 1999. The commission granted amnesty to those who offered full disclosures of the crimes committed.

"Our nation sought to rehabilitate and affirm the dignity and personhood of those who for so long had been silenced, had been turned into anonymous, marginalized ones," Tutu wrote. "Now they would be able to tell their stories, they would remember, and in remembering would be acknowledged to be persons with an inalienable personhood."

In leading the commission, Tutu "touchingly and profoundly demonstrated the depth of meaning of ubuntu, reconciliation and forgiveness," Ramaphosa said on Sunday.

"Desmond Tutu was a patriot without equal; a leader of principle and pragmatism who gave meaning to the biblical insight that faith without works is dead," he said. "We pray that Archbishop Tutu’s soul will rest in peace but that his spirit will stand sentry over the future of our nation."

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born on Oct. 7, 1931, in Klerksdorp, South Africa.

He was a teacher in South Africa before becoming a priest, a vocation that led him to study at King's College London in the mid-1960s. He moved between the United Kingdom and South Africa for the next decade, holding teaching and theological leadership positions, according to the college.

St. Mary's Cathedral in Johannesburg appointed Tutu as dean in 1975, making him the first Black priest to hold the position. Ten years later, he became the first Black bishop of Johannesburg. He was named archbishop of Cape Town a year later, elevating him to the highest position in the Anglican hierarchy in Africa, according to a biography posted by King's College.

"On behalf of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa, the whole faith community, and I make bold to say, on behalf of millions across South Africa, Africa and the world, I extend our deepest condolences to his wife, Nomalizo Leah, his son, Trevor Thamsanqa and to his daughters, Thandeka, Nontombi and Mpho. And all of their families," Thabo Makgoba, Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, said in a statement on Sunday.

On the morning of April 27, 1994, when all South Africans were allowed to enter voting booths, a day that would mark both the end of apartheid and the election of Nelson Mandela as president, Tutu rose early at the archbishop's complex in Cape Town, he wrote in his memoir.

He drove from his residence in a "leafy upmarket suburb" to Gugulethu, deciding "that I would cast my vote in a ghetto township," an action he described as symbolic.

"How do you convey that sense of freedom that tasted like sweet nectar for the first time? How do you explain it to someone who was born into freedom? It is impossible to convey," Tutu wrote. "It is ineffable, like trying perhaps to describe the color red to a person born blind. It is a feeling that makes you want to cry and laugh at the same time, to dance with joy, and yet fearful that it was too good to be true and that it just might all evaporate. You're on cloud nine."