COVID leaves Louisiana front-line workers exhausted as hospitalizations surge: Reporter's Notebook

Our team saw many tears shed today.

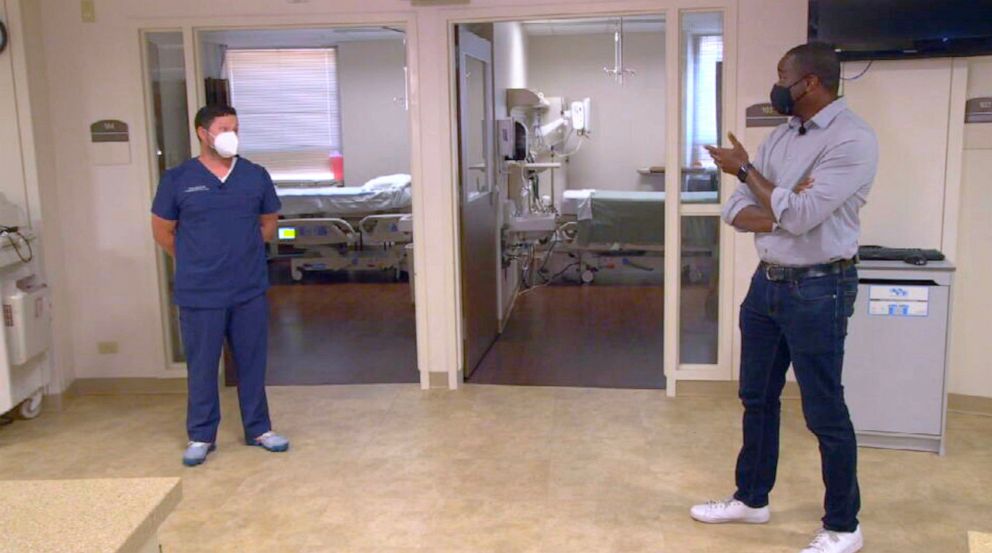

We spent Wednesday morning and afternoon at Willis-Knighton Medical Center in Shreveport, Louisiana, where the medical teams at the health care group's four hospitals are in the throes of yet another coronavirus surge.

In the last six weeks, the number of patients receiving care for COVID-19 surged from just four patients to 88, and today, it's clear that exhaustion and frustration is taking its toll on each member of the staff.

All the health care workers we spoke with -- a pulmonologist, a staff nurse and an intensive care unit charge nurse -- were unable to fight the raw emotion and exhaustion experienced by every one of them.

"I'm not home near as much as I should be," Dr. Kevin Langlois told me, while fighting back tears.

Akin to many other hospitals across the country, the COVID-19 crisis has forced all hands on deck over the past year and a half at Willis-Knighton.

Young nurse Melinda Hunt, too, could not fight back tears, as she described the emotional toll the past year has taken on her.

"I'm putting people my age, and my parents' age, into body bags and it is my worst fear for it to be one of them," Hunt said. "To be honest, I probably cry most days at work. And I cry at home. I'm tired. I've been doing this for a year and half. It feels like it's never going to end."

Staff nurse Sandy Miller said she concealed her own emotions from her husband, as not to be a burden on her family.

"I have to hide it," Miller said. "When I go home, I hide it. I can't go home to my husband [every day] and tell him what a horrible day I've had. When I'm around the grandkids I have my smile on."

Just a few weeks ago, she believed that perhaps, the worst of the pandemic was finally over. But then the delta variant arrived in Louisiana, and the situation rapidly changed.

"These patients are sicker, they're younger. I mean, they're the age of my children," Miller said. "It's tough to see him come in, you know, they're scared, they're young, they don't understand, like, you know, they didn't get the vaccine because they didn't think they needed it. They were young, invincible kids, and they're sick -- it's bad."

The influx of severely ill patients has been increasing rapidly, and the COVID-19 crisis in Louisiana continues to reach levels never before seen during the pandemic. Virus related hospitalizations have skyrocketed in recent weeks, with now more than 2,000 residents hospitalized across the state, according to federal data.

"They get sicker faster. And we have patients on ventilators that are in their 30s, 40s and 50s, which was not the case last year. Last year it was in general an elderly population. Now it's a different game," noted Langlois.

On Monday alone, nearly 400 patients with COVID-19 were admitted to hospitals across the state, marking the highest number of patients seeking care within a 24-hour period in Louisiana since the onset of the pandemic.

"We're just exploding. We're bursting at the seams," Langlois said.

When we asked if there is ever a point when he simply wants to abandon ship, Langlois emphatically said he can never give up, "even when the odds are stacked against you."

The vast majority of patients at Willis-Knighton, regardless of age, are unvaccinated, the health care workers said.

One patient, 75-year-old Curtis Cannon, told our team he will surely get the vaccine once he is released from the hospital

Cannon said he was at first skeptical about getting the vaccine, but now realizes how "real" this virus truly is.

"I think everyone should get vaccinated," Cannon said.

Each health care worker stressed to ABC news that the best way to prevent severe illness and truly protect oneself against the virus is by getting vaccinated.

"If we are ever going to get back to normal, we have to work together ... the vaccines work," Langlois said. "The chances of having a bad reaction to one of these vaccines is far less than getting sick, getting COVID, getting in the hospital, getting on a ventilator, and unfortunately, passing away long before you should."

Hunt said once unvaccinated patients become sick, often, they tell her they will get the vaccine when they get out.

"The question isn't when I get out if, if you get out, because the reality of it is, once you've made it to the ICU, your odds are not good," Hunt concluded.

ABC News' Arielle Mitropoulos contributed to this report.