How COVID-19 keeps a tight grip on the working poor

On a chilly January afternoon, 5-year-old NyAnna House asked her friend Audrey to play.

"Let's go outside and ride bikes," she said, nudging the 2-year-old from her coveted position at the small table where they were sitting in NyAnna's home in a Virginia motel.

The girls leaped off the stoop and raced around the driveway -- the U-shaped parking lot of one of dozens of such lodgings along the Jefferson Davis corridor near Richmond.

As the kids played, a Chesterfield County school bus pulled up in front of the motel, letting a couple of the older children off who live there as well.

Some motels are filling the gap in the state's affordable housing crisis for families like NyAnna's. The crisis has been exacerbated here and elsewhere in the country due to the strain of the COVID-19 pandemic, plunging many into a spiral of financial strife, especially when assistance and eviction protections ended.

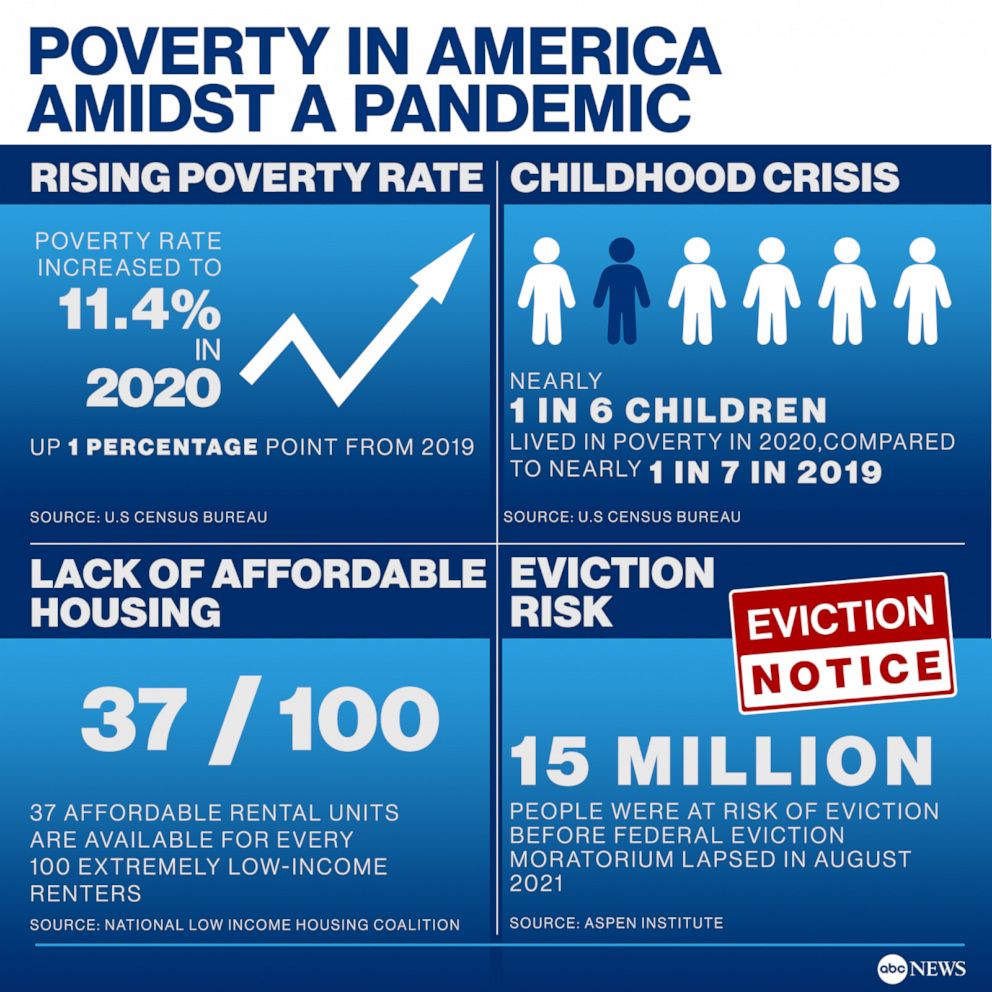

A recent government report found that Virginia lacks about 200,000 affordable rental units. The National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates that nationwide, only 37 affordable rental units are available for every 100 extremely low-income renters.

Poverty has deepened in the United States as well, increasing for the first time in five years in 2020 while median income decreased nearly 3%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. ABC News chronicled the situation of those on the edge, whose situations were worsened by the pandemic and their attempts to escape the grip of poverty.

NyAnna's parents, Nicki Schools and Brian House, both 28, have only lived at the motel for a few weeks, but said they've been bouncing from motel to motel along the corridor for about a year.

Between them, they work three jobs. Schools said she takes care of Audrey five days a week for $85 while House said he just secured a new job doing roadside maintenance for big rigs. He makes $18 an hour, the most he's ever made. Schools also works weekends at Applebee's where she said she can make about $150 on a good night. The motel sets them back $1,140 each month.

Despite their hard work, the couple said the rent and utilities deposits, plus some bad credit, are holding them back from their dream of renting a home or apartment with bedrooms. The median rent for a 2-bedroom apartment in Richmond is nearly $1,400, according to rental platform Zumper.

The federal child tax credit, $300 a month, was a welcomed cushion, covering an emergency car repair and rent when Schools was out of work with COVID-19. The payments ended when the program expired in December 2021.

"She [NyAnna] wants her own room. I promised her a bunk bed. She deserves it. My goal is to be out of here by the summertime," Schools said.

COVID complicates

Two years into the pandemic, data shows that COVID-19 has taken a disproportionate toll on the poor. In Virginia, the largest disparity in the COVID-19 death rate for adults ages 35 to 54 was between those living in poor neighbors and those who were not, according to a state report published in June 2021.

The virus made its way into Schools and House's motel room in mid-December. Schools thinks she was exposed while working at Applebee's and wondered if some employees came to work sick but were not able to take unpaid time off.

House and NyAnna didn't get sick, but the nearly three weeks Schools said she took away from work set her back. They used their last monthly child tax credit to help pay for their room and watched as their meager savings dwindled back to zero.

Square one. They had been here before.

When Schools was feeling better, she had to come up with a negative COVID-19 test to return to work. She managed to find one home test early on. It cost her $30 but she was still positive for COVID-19. She purchased another test from her sister for $15 towards the end of her illness when she was trying to return to work, but she was still positive. Money was tight and she couldn't afford another $30 hit. So she went to the pharmacy for a PCR test. It was free but the results would take three days -- three days longer without a paycheck. Instead, she said the PCR results took six days to come back.

COVID-19 and working mothers

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, mothers have suffered the most job loss because of the pandemic. School closings, quarantines and childhood infections have left many mothers scrambling to manage work and home life. Many have left the workforce. For single mothers, the options are fewer. In September 2020, the Pew Research Center found that "Black and Hispanic unpartnered mothers each experienced about a 10-point decline in the share employed and at work from September 2019 to September 2020."

The trauma of being a single parent is real.

In Birmingham, Alabama, Jane Johnson, 29, a single, Black mother, who has dealt with job loss and the threat of eviction because of COVID-19, knows she is part of that statistic.

"Of course, it has to do with race," she said.

At the onset of the pandemic, Johnson worked at an Amazon warehouse making $15 an hour, but her son, King Karter, 3, got sick during the first COVID-19 wave in spring 2020. He is asthmatic and Johnson was worried. Her son slowly improved. She said her bosses at Amazon seemed understanding, so she returned to work after a two-week absence. But when her son became ill a second time in as many months and she took another two weeks off, she was fired.

She said she had taken too much time off to care for her son and had negative 46 hours of unpaid time off. ABC News had reached out to Amazon but did not receive a comment by deadline.

"The trauma of being a single parent is real," Johnson said.

Evictions in a pandemic

A major lifeline during the pandemic – the federal eviction moratorium – shielded vulnerable Americans from homelessness, until it ended in August. Before it lapsed, an Aspen Institute report found that some 15 million people were at risk of eviction, with Black renters and those with children especially impacted. With no federal data available, evictions are difficult to track.

While the nationwide eviction moratorium was in effect, Johnson said she found herself behind on rent and her bills were piling up. She used the entirety of her stimulus checks to pay overdue power bills. Her lights had been turned off because of late payments and the fee to reconnect was $1,000. Then came the eviction notice in December 2020.

"How am I supposed to make this work? And provide for a child?" she said.

Johnson said she was confused about how there was supposedly an eviction moratorium yet each day saw neighbors in her apartment complex being evicted before and after the moratorium lapsed.

"I pass the dumpster every day and it's full of people's lives – their beds, strollers, everything," she said.

Johnson was connected to a local anti-poverty group which she said immediately paid her three months of back rent. Another nonprofit, Childcare Resources, took over her weekly childcare expenses, worth about $250 per week. That was enough to get Johnson back on her feet. She took a job at American Family Care as a medical receptionist making $12.50 an hour, and recently got promoted to medical assistant, earning $13.50 an hour. It's a step back from the $15 she was making at Amazon, but it's in the field she wants to be in. Johnson dreams of being a nurse midwife. She earned a doula certification and now has a couple clients. When she can start saving, it will be for nursing school.

"The [Black] maternity mortality rate is high. I want to fix that and make a difference," she said.

Door Dashing

Her full-time job doesn't give Johnson much wiggle room after her $1,000 rent. To make ends meet, she delivers food for the popular delivery app, DoorDash.

On a Friday night in early November, she realized as it started to rain that it would be a good night to "door dash."

"People don't like to get out in the rain. Tips might be good," she recalled.

Johnson can make deliveries with her son riding along, happily watching cartoons on his tablet while she makes a $15 tip delivering a bag of lemonade from Red Robin to a couple living 20 minutes away.

But trouble started when, on the way to deliver the lemonade, Johnson's 2011 Nissan Altima started to overheat. As the windshield wipers wildly beat the driving rain away, Johnson sat up further and further in her seat, as if her proximity to the temperature gauge would somehow bring it back down. She was panicked. Without her car, she couldn't "door dash" and without the extra income, she couldn't make ends meet.

A quick stop for coolant, a call to the thirsty customer about the delay and she was back on the road with the lemonade. King Karter began to cry. It had been a long day and he was tired. Plus he had to go to the bathroom. Johnson cut the night short -- between an overheating car and a crying toddler, it wasn't worth it.

Johnson pulled back into her apartment complex and with a heavy sigh, she turned off the car. Her son had fallen asleep and as she gently roused him from his slumber, she noticed that he had an accident in his car seat.

Family history

Upward mobility in adulthood is linked to the time people spend in poverty as children. In other words, the "American Dream" is harder to achieve for children growing up in poverty. The American Rescue Plan, and specifically the child tax credit, was seen as a way to alleviate the staggering statistic that nearly 1 in 6 American children are growing up in poverty, according to the latest U.S. Census Bureau data.

"This has the potential to reduce child poverty in the same way that the Social Security reduced poverty for the elderly," President Joe Biden said on the day the program was rolled out.

When Tykirel Jordan, 24, of Birmingham, Alabama became homeless with her 3-year-old daughter, she said that she wasn't scared. Growing up the second oldest of eight children, she had been there before. She and her siblings had experienced homelessness as children when their mother couldn't make ends meet.

It causes stress, anxiety and depression.

But in August 2019 she faced eviction. All the dominoes began to fall when her daughter, Alaysia, who was born with respiratory problems and severe asthma, was hospitalized for seven days in the spring of that year. Jordan couldn't work. Like most mothers, she wanted to be by her daughter's side as she battled for breath. At home, her lights had already been turned off by the electric company for nonpayment, she said. After the hospital stay, she lost her job and the eviction notice followed shortly after.

Jordan worked temp jobs as often as she could. Those days she would splurge for a hotel room for her and her daughter for the night. On days she couldn't get work, they slept in her car.

"Alaysia's Social Security check and temp work is how we survived," she said.

After four months of bouncing between her car and the occasional hotel room, Jordan discovered Youth Towers, a program helping young people between the ages of 19 and 26 find permanent housing. The program helped Jordan find an apartment she could afford. It works on a graduating scale. For two months, they covered her entire rental expenses, then half of it, then only a quarter of it, and now Jordan is responsible for the monthly $650 payment.

"If I didn't discover Youth Towers, I would be in the same situation -- room to room or in the car with a sick baby," she said.

Today, Jordan works with Youth Towers. She is a dance instructor for a troupe of young girls whose own parents are seeking housing assistance in the program. Still, she knows how easily she could be back to living in her car. She worries about Alaysia's asthma and how a trip to the hospital could be a financial setback to her personal, economic recovery.

"It causes stress, anxiety and depression," she said.

The razor's edge

Jordan is no longer homeless. As long as Johnson's car holds up, she can make ends meet. And House and Schools are crossing their fingers that if they can save enough in the next couple of months, by summertime they can find a landlord who will overlook their credit flaws and rent them their very own apartment.

But for them, and thousands of Americans like them, they remain on the razor's edge. Any expense -- a car repair, a hospital visit or even a bout of COVID-19 that could leave them out of work -- could be the difference between having a place to live and homelessness.

A 2021 report by the Pew Charitable Trusts breaks down how poverty has increased in the United States despite a more general economic recovery. The author cites a December 2020 study by the University of Chicago and the University of Notre Dame which found that "poverty has risen sharply, however, in recent months as some of the benefits that were part of the government relief package have expired. Poverty rose by 2.4 percentage points from 9.3 percent in June to 11.7 percent in November, adding 7.8 million to the ranks of the poor."

The statistics are worse for people of color.

Kelly King Horne is the executive director of Homeward, a group in Richmond, Virginia, working to end homelessness. Giving people money works, she said, adding that oftentimes people living in poverty are really good at managing a shoestring budget.

"I think having a really robust safety net that does more, that's powerful because it's an investment in community strength and resilience. Because you don't always know who is going to need it … the pandemic stripped away some of the assumptions [about poverty]," she said.

Two steps forward, a million steps backwards.

On a weeknight in mid-January, House returned to the motel after work at his usual time: 4:30 p.m. The plan was that he would run to the store for microwave dinners, a go-to for the family of three living without an oven. His cousin had recently gifted them a double electric burner but they did not own any pots or pans -- home-cooked meals would have to wait. With a hard workday behind him and unseasonably mild weather at hand, House opted to take his family for a drive.

They piled in the car for a home-cooked fettuccine Alfredo at his mother's house, nearly an hour away. Many nights, dinner is leftovers from Applebee's. NyAnna's favorites are french fries and cheese sticks. Finding money for food is often a challenge. Weekly food deliveries made by A Place of Miracles Cafe, a nearby food bank whose mission is to serve those living in the motels along the Jeff Davis corridor, ease some of the strain.

"As soon as I started working at Applebee's, they cut my food stamps off," Schools said, meaning her income put her over the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program's state income limit to qualify for assistance.

"Two steps forward, a million steps backwards," House said.

Julia Rendleman is a freelance journalist based in Richmond, Virginia, focusing on issues of human health and housing. This project was supported by a grant from Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, a network of mayors advocating for guaranteed income programs in their cities. The people featured in this story are not recipients of or applicants for guaranteed income programs.