Photos: How the 1918 flu and COVID-19 pandemics compare

Editors note: Some of the images below are animations showing two images and may take longer to load.

There are strong parallels between the COVID-19 pandemic and the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed at least 50 million worldwide, including an estimated 675,000 Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The U.S. has now surpassed 675,000 deaths from COVID-19 making the current pandemic the deadliest in U.S. history. As of Sept. 20, more than 228 million people have been infected with COVID-19 worldwide, More than 4.6 million have died across the globe, according to real time data compiled by Johns Hopkins University.

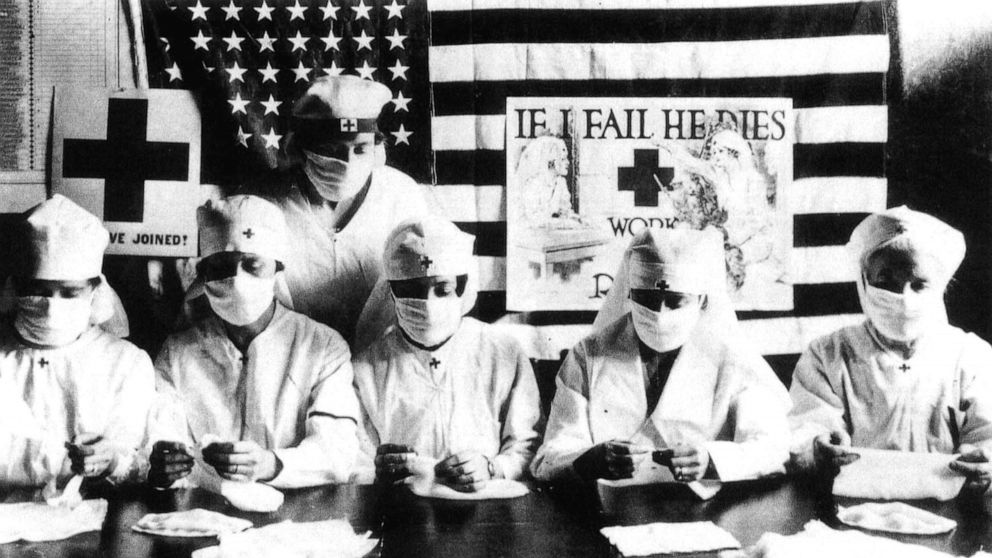

Photos: Red Cross volunteers fight against the flu pandemic in the U.S. in 1918. | A doctor collects details of a person suffering from fever before conducting a swab test for COVID-19 at Guwahati Medical College Hospital in Gauhati, India, May 17, 2020. Credit: Anupam Nath/AP

Here’s a look at how the two pandemics compare.

In 1918, the first flu cases were reported in March at an Army base in Kansas. Without testing capabilities, the flu spread widely and easily. The movement of military during World War I aided the spread.

The first confirmed COVID-19 case in the U.S. was on Jan. 21, 2020. A man in his 30s from Washington state had traveled from Wuhan, China, where the novel coronavirus is believed to have originated. The highly contagious coronavirus spread quickly across the globe, aided by air travel.

Social distancing and mask wearing

During the flu pandemic, the only hope was social mitigation efforts. The development of flu vaccines didn't happen until the 1940s. Health officials understood that mask wearing, social distancing and frequent hand-washing helped slow the spread. Cities that embraced efforts such as mask mandates and social distancing, along with the closures of businesses, schools, theaters and houses of worship, saw lower numbers of deaths. A similar pattern has occurred now.

Back then, many masks were made of gauze and cheesecloth and held in place with elastic or tape.

With COVID, people were encouraged to make homemade cloth masks because of a shortage of medical masks that left even hospital workers without sufficient supplies of masks as well as other personal protective equipment.

Photos: Seattle police officers wear protective gauze face masks during 1918 flu pandemic. Credit: The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images | New York City police officers wear face masks at the Fordham bus hub in the Bronx borough of New York, April 2, 2020. Credit: David Dee Delgado/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Photos: A man receives a shave from a barber during the flu pandemic in Chicago, 1918. Credit: Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection/Chicago History Museum/Getty Images | Barbers Steve Grimaldi and Chris Pouch cut hair for customers at Grimaldi's Barber Shop on May 13, 2020, in Chesterton, Indiana. Credit: Scott Olson/Getty Images

Though medical professionals urged mask wearing in 1918, many people resisted, just as they have during the current pandemic for similar reasons. Mask mandates came and went across the country during the flu pandemic. Officials worked to characterize mask use as a patriotic effort.

Photos: Two men wearing face masks advocate the use of masks in Paris during the flu epidemic. Credit: Topical Press Agency/Getty Images | Nurses protest in front of the White House against the lack of personal protection equipment for COVID-19 on April 21, 2020, in Washington, D.C. Credit: Win McNamee/Getty Images

San Francisco was the first U.S. city to mandate the wearing of face masks in October 1918. People were fined and imprisoned for failing to comply. The mandate was only in place for four weeks initially, with the spread of the flu curtailed briefly. The ordinance was re-instituted again in January 1919 as cases spiked.

The Anti-Mask League, formed in San Francisco in January 1919, protested the wearing of masks, viewing it as an unconstitutional limit of individual liberty. The refusal to wear masks and socially distance didn’t become as politicized or as organized as it has these days, however. The League’s efforts seemed to have been a rare exception. Most people complied with the ordinances.

Photos: Court is held outdoors in a park due to the flu pandemic in San Francisco, 1918. Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty Images | New York City Criminal Court Judge Paul McDonnell works remotely from his Brooklyn apartment due to the coronavirus pandemic on April 09, 2020, in New York City. Credit: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Reopening too early

The 1918 pandemic occurred in three waves: the first in the spring, the second, far deadlier wave, in the fall, and then the final wave in the winter/spring of 1919.

Cities, such as New York, were hard hit by the coronavirus in the spring of 2020. Then case numbers subsided through the summer and mitigation efforts were eased in many places. Then a resurgence of cases emerged in the fall and winter in both urban and rural settings as well as worldwide.

During the flu pandemic various measures to contain the spread were taken inconsistently across the country. In 1918, there was a first wave and then a flattening of the curve. Many places such as California lifted restrictions too early, leading to a second wave of infections. The same situation has occurred with the COVID-19 pandemic. California was initially successful in the battle against COVID-19, but then faced a dire situation this past winter.

Photos: Naval Aircraft Factory float passes crowds in the Liberty Loan Parade in Philadelphia, Sept. 28, 1918. Credit: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command | Motorcyclists ride down Main Street during the 80th Annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally on Aug. 7, 2020, in Sturgis, South Dakota. Rally officials estimated there were more than 250,000 attendees. Credit: Getty Images

In late September 1918, Philadelphia’s decision not to cancel its Liberty Loan parade, held to pay for the war effort, took a toll. In October, more than 10,000 people died from the flu in the city. At one point, the city had more than 500 bodies waiting for burial. Cold-storage plants needed to be used as temporary morgues and packing crates were utilized as coffins, according to the CDC.

In parts of the country, hospitals were so overwhelmed with patients that makeshift hospitals were created in schools and other buildings. The 1918 flu took an estimated 195,000 American lives in October 1918 -- the deadliest month of the pandemic.

Photos: Warehouses were converted to keep the infected people quarantined during the 1918 flu pandemic. Credit: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images | A new field hospital built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and members of the National Guard, featuring 437 beds for coronavirus patients, is opened at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center, May 11, 2020, in Washington, D.C. Credit: Win McNamee/Getty Images

During the current pandemic, many parts of the U.S. never shut down to slow the spread of the coronavirus. For example, South Dakota welcomed hundreds of thousands of people for a 10-day biker rally in Sturgis. According to The Associated Press, at least 290 people in 12 states who attended the rally tested positive for COVID-19. The Washington Post reported that South and North Dakota, along with Wyoming, Montana and Minnesota, led the country in new infections per capita weeks after the rally. With attendees from all across the country, however, and the lack of contact tracing, documenting the full extent of the spread from the event was difficult.

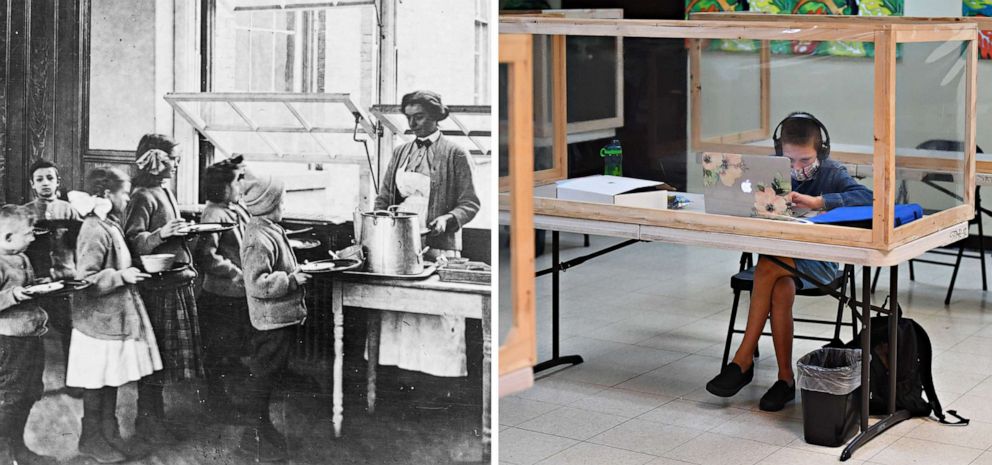

Schools

While many places closed schools in 1918, three cities -- New York, Chicago and New Haven, Connecticut -- did not. In New York, classroom windows were kept open and children studied on rooftops and other outdoor spaces even through the cold winter months. Schools in the city were deemed to provide better health conditions than crowded and unsanitary tenements.

Photos: Children stand in food line with open windows for ventilation at Public School 51 in New York City, 1900-1920. Credit: Library of Congress | A student follows along remotely with their regular school teacher's online live lesson from a desk separated from others by plastic barriers on Sept. 10, 2020 in Culver City, Calif. Credit: Getty Images

In late 2020, New York City was the only major U.S. city to reopen public schools for in-person learning with a hybrid model, with some days in-person and others involving remote learning. A mask mandate and social distancing measures were put in place. COVID-19 testing protocols were also implemented. Schools opened and closed in the city based on city-wide infection rates and cases within individual schools. A patchwork response across the country included fully remote learning and a return to school with no mitigation measures such as mask mandates.

Holiday periods

Both pandemics saw spikes in case numbers due to family gatherings and holiday celebrations. In a Dec. 12, 1918, Boston Globe article, Dr. M. Victor Safford of Boston’s Health Department was quoted as stating, “Most of the influenza cases reported in Boston today are traceable to visits to homes of persons who have been or are ill with influenza.”

Despite an explosion in COVID-19 cases across the U.S. and warnings from the CDC, more than three million travelers passed through TSA screening checkpoints in the run-up to Thanksgiving in 2020. The American Automobile Association (AAA) predicted almost 48 million Americans would travel by road for the holiday and another 84.5 million would travel between Dec. 23 and Jan. 3. In the four-day period right before Christmas, more than four million people traveled by air. That was the largest period of air travel since the pandemic began last March.

The holiday surge put coronavirus hospitalizations at their highest levels since the spring of 2020.

On Jan. 19, 2021, it was reported by Philadelphia ABC station WPVI that 18 members in one family tested positive after a holiday party in Pennsylvania.

In the spring of 2021, young people flocked to spring break locations despite the ongoing pandemic. Miami Beach police faced unruly crowds and dispersed a crowd with pepper balls after two officers were injured. Dr. Fauci attributed the rise in cases in part to people traveling and states easing restrictions too soon.

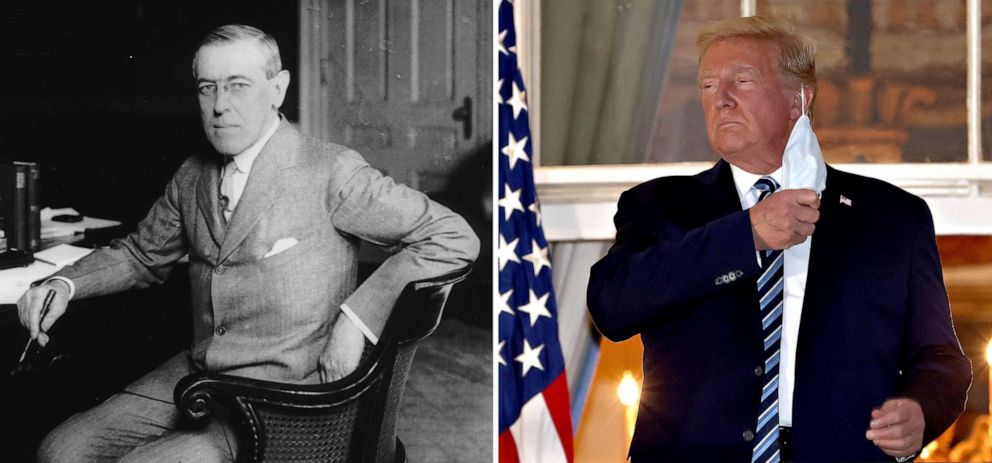

Leadership

In 1918, “there was no leadership or guidance of any kind directly from the White House,” historian John M. Barry, author of "The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History," told TIME magazine. President Woodrow Wilson was so focused on the war effort. “Hundreds of thousands of Americans died without President Wilson saying anything or mobilizing nonmilitary components of the U.S. government to help the civilian population,” according to the book “Shall We Wake the President: Two Centuries of Disaster Management from the Oval Office” by Tevi Troy. Wilson suffered from the flu in April 1919 in the middle of peace negotiations to end World War I.

Photos: Patients rest in beds in The American Ward at Fourth Scottish General Hospital, where most patients were influenza cases from incoming military convoys, in Glasgow, Scotland, Nov. 1918. Credit: Getty Images | COVID-19 patients are treated inside a non-invasive ventilation system named the 'Vanessa Capsule' at the municipal field hospital Gilberto Novaes in Manaus, Brazil, May 18, 2020. Credit: Felipe Dana/AP

The federal government response to the COVID-19 pandemic throughout 2020 was widely criticized. Former President Donald Trump repeatedly downplayed the severity of the crisis. States were largely left to manage the crisis on their own. Many in the White House, including the president and vice president, as well as Republican members of Congress, openly refused to wear masks. Trump contracted COVID-19 in October 2020. One coronavirus outbreak infected 34 White House staffers.

Photos: Woodrow Wilson. Credit: Getty Images | President Donald Trump removes his mask upon return to the White House from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, where he was hospitalized for COVID-19, on Oct. 05, 2020 in Washington. Credit: Getty Images

The 1918 flu took a heavy toll. The pandemic lasted two years. Entire families were wiped out and many of those who survived were widowed or orphaned. There was a significant economic impact as well. The pandemic finally ebbed after a third wave by the summer of 1919. It is believed the flu strain became so widespread that a level of herd immunity developed from infection as flu vaccines were not available.

COVID-19 vaccines

Medicine and science have come a long way since the 1918 pandemic. Vaccines for COVID-19 were developed with unprecedented speed, but not before a huge loss of life, economic devastation and the suspension of normal life. Within nine months, the U.S. authorized the first COVID-19 vaccine for people 16 and older on December 11, 2020. Vaccination programs in the U.S. began ramping up in late 2020 in the U.S.

By early 2021, the U.S. had three vaccines given emergency authorization, the federal government secured hundreds of millions doses and opened up more and more vaccination sites. Incoming President Joe Biden set a goal of 100 million COVID-19 vaccine doses to be administered in his first 100 days in office beginning Jan. 20, 2021. That goal was reached on Day 59.

U.S. vaccination rates in the spring of 2021 allowed for the easing of pandemic restrictions across the country. Cases declined and vaccination rates rose with more than half American adults fully vaccinated. Memorial Day weekend marked a dramatic return to more normal life.

The "hot vax summer" of 2021, meant to celebrate the return to normalcy and fun activities, hit roadblocks. The politicization of vaccines, like masks, along with the emergence of a new, more infectious virus variant, delta, complicated the ability to end the pandemic. Vaccination rates stalled. Just 63.8% of the U.S. population over 12-years-old is fully vaccinated, according to the CDC as of September 20. Many parts of the country have much lower rates with many Americans refusing to be vaccinated. Twenty one months into the pandemic, we still don't have enough people vaccinated to slow the virus in the U.S., much less the rest of the world.

Dr. Rochelle Walensky, CDC's director, said on September 19 that well over 90% of people in the U.S. hospitalized now for COVID-19 are unvaccinated. Breakthrough infections among vaccinated people are happening and there are concerns about waning vaccine immunity. There is still no vaccine authorized for children under 12-years-old.

The ideological battle continues to rage across the country over vaccine and mask mandates. In several states, Republican governors have banned mask mandates in schools as students nationwide returned to their classrooms this fall. Some have also banned vaccine passports.

Many experts view what is happening now as a preventable tragedy. The current pandemic is far from over.

ABC News Photo Editor Alex Scott contributed to this report.