Columbine survivor still battling invisible wounds 20 years on has a quest to help others

Missy Mendo was in math class when she heard a banging and a rumbling. She peered out the window -- and the looks on her peers' faces outside sent a jolt through her that this was something serious.

When Mendo and her classmates ran to the hallway, she realized the rumbling was the sound of students running. They fled the building as the fire alarm blared.

I felt selfish, almost, in being able to hug my parents.

When they reached a park across the street, "they started shooting at us in the park," she told ABC News. Mendo grew up around guns so knew the sound -- but she was used to guns being fired away from her, not toward her.

She and her classmates ran into a nearby house where they found other shaken students waiting in line to call their parents and let them know they were safe. When she got home later, her family's answering machine was overloaded with calls from frantic parents asking if she had seen their children.

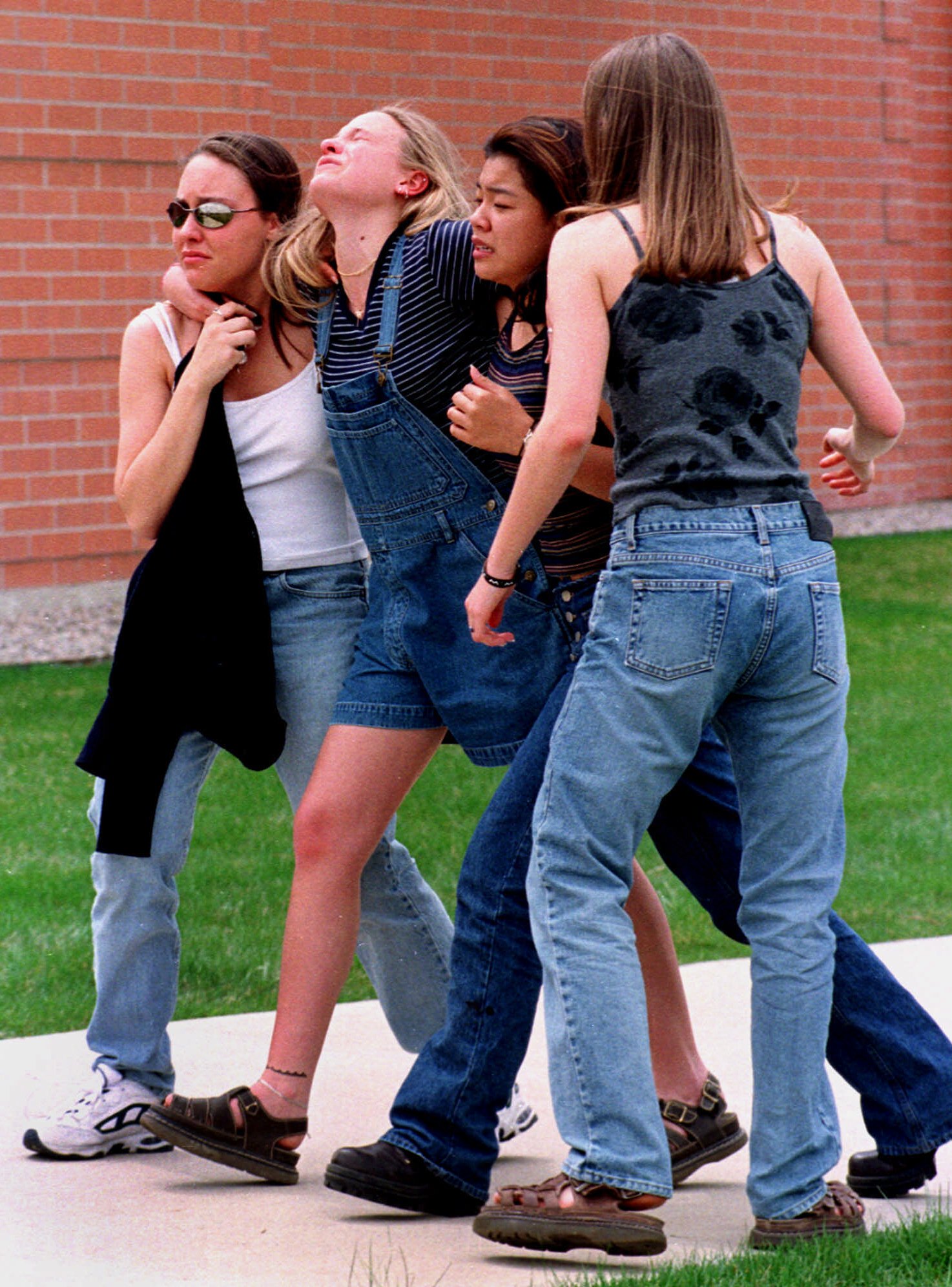

That day -- April 20, 1999 -- changed the life of Mendo, her Columbine High School classmates, their families and the Littleton, Colorado, community forever. As Americans were glued to their TVs, watching as students sprinted from the school with their hands over their heads, Mendo and the country learned the tragic reality: two students opened fire at Columbine High School, murdering 12 classmates and one teacher before killing themselves inside the building.

Most survivors escaped without bullets in their bodies, but for many, including Mendo, the shooting inflicted invisible wounds of emotional trauma through high school and beyond.

Since working through her own trauma, Mendo has been on a mission to help the shooting survivors who came after her.

Those first days following the massacre, Mendo said she avoided hugging her parents due to survivors' guilt.

"There were other parents who didn't get to hug their children that night, and I felt selfish, almost, in being able to hug my parents," she said.

As students returned to school, Mendo was grateful for the administration, who, she said, poured their hearts into making the environment feel uplifting and secure.

School felt "like the safest place in the world, because it couldn't have happened twice," she said. "But then again, we thought it couldn't have happened in the first place."

While the school itself felt secure, for Mendo and many of her classmates, working through the trauma wasn't as simple.

The tragedy at Columbine certainly wasn't the first school shooting, and it came only one year after the Jonesboro, Arkansas, middle school shooting which killed five.

But Columbine's then-principal, Frank DeAngelis, told ABC News he felt he was without a road map for how to help his students through the trauma.

Therapists were offered, but not required, he said, and many students declined to speak to someone, only to realize years later how helpful it would've been. Or some, like Mendo, accepted help, but didn't have long-term options.

Mendo said she was assigned one therapist -- who did not specialize in PTSD -- and was offered eight free sessions, without options of alternative therapists or ways to set up long-term mental health care.

I think about my baby's first day of school which terrifies me.

And in the wake of Columbine, Mendo was diagnosed with insomnia -- something she's still struggling with today.

"It shows up in different ways," she explained. "One being, I'm a new mom, and I think about my baby's first day of school, which terrifies me. Two, if I have a deadline for work or if I have an important event coming up, I do not sleep the night before at all. The next day you're tired, then it just repeats itself for a few days. It's almost like a mental hangover."

Mendo said three recent mass shootings "set off triggers" for her.

The first was the December 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, which took the lives of 20 young children and six educators.

"That one was awful," she said. "I felt that for months and months and months afterward."

Second was the October 2017 shooting at the Route 91 Harvest Music Festival in Las Vegas, which killed 58 people, becoming the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history.

Third was the February 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, which claimed the lives of 17 students and staff.

The Parkland massacre especially hit home for Mendo.

"I saw [on TV] the kids coming out of the school with the hands on top of their head," she said, calling it "eerily similar" to her experience.

Parkland survivors have a special place in Mendo's heart, as she wants to be a support system for the school shooting survivors who followed her.

She serves as community outreach director of The Rebels Project, a non-profit -- named after the Columbine High School mascot -- that connects mass shootings survivors with each other to find a support system.

One of her missions is bringing about improvements for the ways their mental health trauma is treated.

We're here for the long run, because we know what that feels like.

"I feel like mental health has come a long way, but the stigma of mental health still exists. It's an injury you cannot see, and that is why I feel there's such a taboo with making it a regular part of somebody's health checkups," Mendo said.

DeAngelis, the Columbine principal, said in 1999 he was discouraged from disclosing he was seeing a therapist in case he'd be "deemed unfit for duty."

One of The Rebels Projects' new initiatives is a tool kit for mental health resources for survivors, and for Mendo and her fellow advocates, the stakes for developing these resources couldn't be higher.

Just last month, two teenage Parkland shooting survivors died in apparent suicides. The tragedies came the same month as the apparent suicide of the father of a Sandy Hook victim.

Around 20 years ago, the Columbine community saw two suicides after its own tragedy.

"We sympathize with Parkland because we understand what they're going through. We've gone through it. These kids need help for the long run. It's the saddest thing in the world," Mendo said. "We're here for you, we care and we want to help you -- not just for today not just for tomorrow... we're here for the long run, because we know what that feels like."