Colorado River is America's most endangered; ranchers work to combat climate change

The Colorado River, a major freshwater source for over 40 million people in seven southwestern U.S. states and parts of northern Mexico, has lost 20% of its water levels over the past 22 years and environmentalists forecast it's going to get worse.

Farmers and other agriculture workers have been especially hit by the water loss as the fields have dried up, making it harder to cultivate crops and cattle.

"We've really been working on some of this for two decades. You know, we've kind of seen this coming," Paul Bruchez, a fifth-generation Colorado rancher, told ABC News.

Now Bruchez, his family, other ranchers and farmers are teaming up with conservationists to adapt to the changing environment and try to repair some of the damage, and they hope that they can encourage others to step up before it's too late.

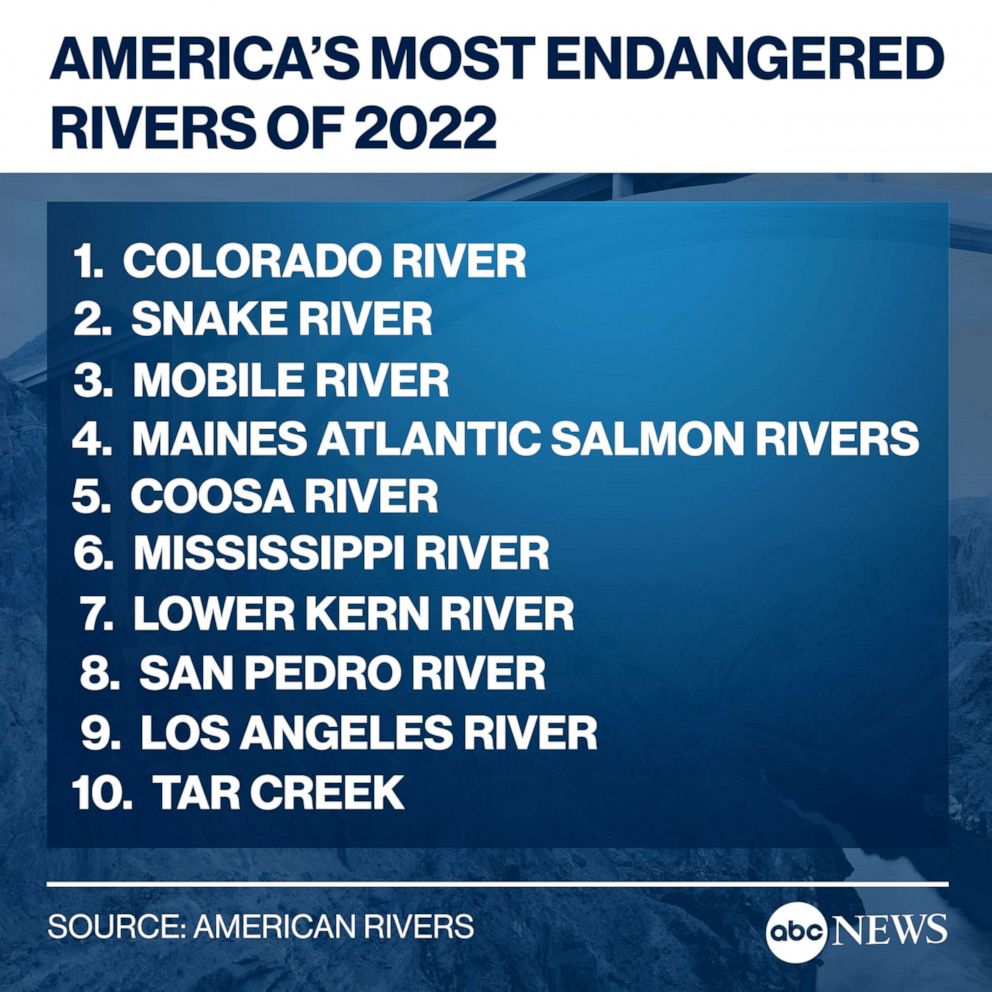

Twenty-three years of drought conditions in the West and Southwest have resulted in the lowest water levels at the Hoover and Glen Canyon Dam reservoirs since they were filled. The Colorado River is now at the top of the country's most endangered rivers list, according to the non-profit American Rivers.

The conservationist group released its updated list of endangered U.S. rivers Tuesday, which includes Snake River in the Northwest, the Mobile River in Alabama and Maine's Atlantic Salmon Rivers.

"We're faced with this, this new reality where we have to learn to live with less water," Matt Rice, the southwest regional director for American Rivers, told ABC News.

Bruchez said ranchers have been hit hard, because without the freshwater supply, the forage isn't fertile enough for livestock to feed on. He said his family had to sell half of their livestock due to poor land conditions.

"Mother Nature is key for our business," he said.

Bruchez, who sits on the Colorado Water Conservation Board, however, isn't taking the climate crisis lying down and has implemented ecological projects to mitigate the damage and restore the river.

Working with conservationists, Bruchez installed five artificial riffles along a 12-mile stretch of the river. The riffles use cobbles at parts of the river that cascades down and promotes irrigation and invertebrate growth at low water level areas.

"It is this region's adaptation to climate change," he said.

Bruchez's family has also worked on restoring the soil so that it can make use of what little water it does get.

Doug Bruchez has worked with his brother to bring in specialized plants and forages that are better suited to the fields around the river.

"We are looking for drought-resistant plants, we are looking for plants that will use less water," Doug Bruchez told ABC News.

Paul Bruchez said since his family rebuilt a meadow using this drought-resistant flora, the livestock has been liking their feeds "significantly better."

"The nutrition value of the feed is higher, and we use them as a tool to assist us in managing the soil," he said.

Rice said these Colorado River restoration projects have "quantifiably improved the habitat and the environmental health of the river."

"We're actually implementing them kind of in real-time right now. If we weren't doing that, not only would it have a tremendous impact on the communities upstream of here, the agricultural communities, it [would have] a tremendous impact on the environment," Rice said.

Bruchez said he is looking to expand these programs throughout the Colorado River basin and improve the water and soil conditions throughout the southwest.

Bruchez said of his efforts and outreach that "it is both an honor and terrifying," but in the end he hopes that they can make a difference.

"These are tough conversations when people realize that survival will require adaptation," he said. "Without adaptation, we wouldn't be here for our generation [and] the generation after us."