Chasing Hillary: The challenge of covering Clinton in the modern media era

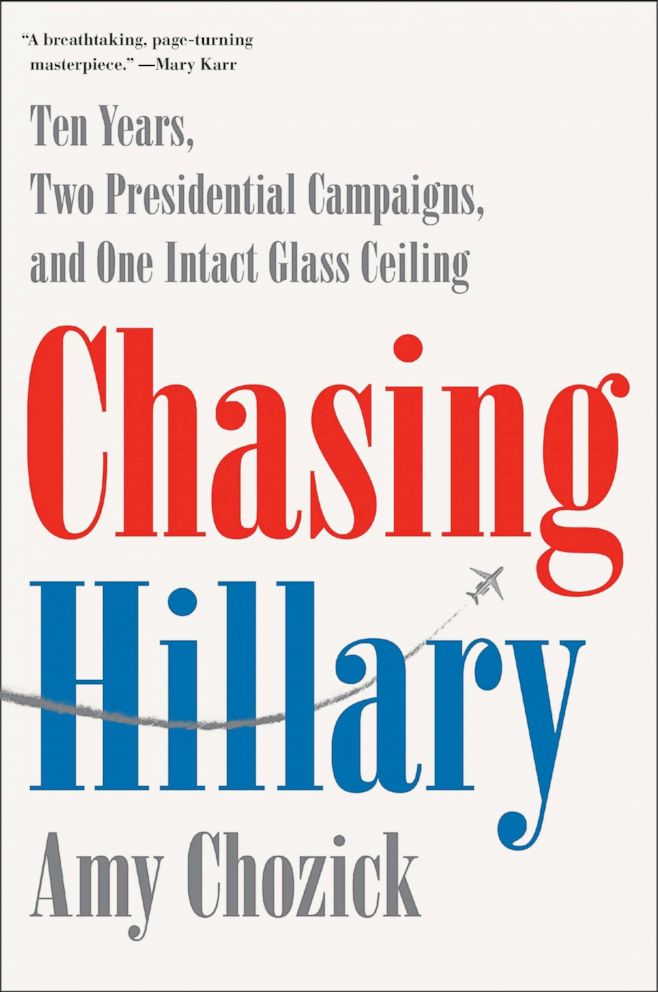

Amy Chozick’s memoir of her time reporting on Hillary Clinton is less about life on the campaign trail and more of a dissection of how she says campaign coverage has changed – for the worse – in the lightning-fast era of social media.

In her new book, “Chasing Hillary,” Chozick questions the decision of her paper, the New York Times, to so extensively cover the hacked Democratic emails, concluding that she and other reporters and news organizations had been used by Russian intelligence.

She also lamented about the lack of press access to those who want to be the next leader of the free world, noting the walls of aides that guard them from making any kind of mistake that could become a gif replayed endlessly on social media.

The book veers back and forth between her work for the New York Times in the 2016 contest, her time covering the 2008 election for the Wall Street Journal, and also delves into details of her personal life and her struggle to have one during the busy campaign season.

But the most memorable parts from the 375 pages are her insights into the news media’s coverage of 2016 campaign and the Clintons’ relationship with the press.

Here are five takes from “Chasing Hillary”:

Clinton couldn’t define her candidacy

Why did Hillary Clinton run for president?

The former secretary of state struggled to articulate why voters should vote for her other than to argue that she was extremely qualified for the job and Donald Trump wasn’t.

It’s not a short, made-for-media (or even made for a bumper sticker) message like the ones that Trump – "Make American Great Again" – or Obama – "Yes We Can" – were able to use to capture voters’ imagination and energy. They were positive messages of hope for a group of voters who were struggling.

Clinton didn’t have that.

“Her only clear vision of the presidency seemed to be herself in it,” Chozick writes.

And, she notes in her book, Clinton seemed to dislike the campaign process.

“If there was a single unifying force behind her candidacy, it was her obvious desire to get the whole thing over with,” she wrote.

While Chozick doesn’t offer the minute-by-minute, detailed minutiae of strategy decisions made by Clinton's Brooklyn headquarters, she does use campaign struggles to illustrate a larger point about Clinton, such as her lack of a strong message.

The struggle to find a campaign theme is one Chozick uses to demonstrate how Clinton couldn’t define her candidacy nor explain why she wanted to be president.

The phrase Clinton repeatedly used on the stump was that she wanted to help “everyday Americans.”

It wasn’t connecting with voters and Clinton knew “it wasn’t working,” the author writes, but no one on her team had a better suggestion.

“It was never about the slogan,” Chozick noted, “it was about Hillary’s inability to articulate why she wanted to be president. It was about Hillary, who’d be so in touch with struggling voters eight years earlier, not begin able to see that Americans had to be pretty pissed off to no longer want to be called middle class.”

After testing 84 replacements, and, yes, Chozick lists them all, headquarters decided on “Fighting for Us,” “Breaking Down Barriers,” and “Building Ladders of Opportunity.”

Of course, the phrase most remembered with Clinton is the one that came out of the Democratic convention in Philadelphia: “I’m with her.”

And that’s not exactly a positive message for voters either.

Clinton’s relationship with the press

The Clintons don’t like the press. Both Bill and Hillary Clinton have long had an adversarial relationship with the Fourth Estate with numerous examples of conflict going back to the days of the Whitewater controversy in Bill Clinton’s White House years.

But Chozick argues it was even more difficult for her as a reporter with New York Times. “It was something specific to the Times,” she wrote. The Clintons believed “the paper was out to get them.”

And, despite being the New York Times reporter assigned to cover her campaign, Chozick notes Hillary Clinton never called her once. And, yes, Donald Trump did.

In fact, the only interactions Chozick describes with the Democratic presidential nominee are accidental ones: Clinton walked in on her in campaign plane bathroom and how Clinton almost accidentally took a selfie with her on the campaign rope line.

The conflict with the Clintons continued with the next generation on Wednesday morning, when Chelsea Clinton tweeted a number of critical tweets to Chozick, questioning items the author wrote about her and asking if the book was fact-checked.

Hi @amychozick! The 1st line (“Things were already looking bad when Chelsea Clinton popped the Champagne”) is false. I would have been happy to tell you that if you’d asked, which you didn’t. Looking forward to the correction once you fact check. Thanks! https://t.co/gqppfDEEW1

— Chelsea Clinton (@ChelseaClinton) April 20, 2018

Hi @amychozick! Hearing there are more tidbits about me in your book which were easily fact checked and you fact checked...none of them. Here’s an easy one: I’ve never gotten hair keratin treatment. The others would have been equally easy!

— Chelsea Clinton (@ChelseaClinton) April 24, 2018

Chozick responded by tweeting the author note from her book in which she explained how she hired a fact-checker.

Hi Trina, I hired a professional fact checker. Here's the Author's Note explaining my process. pic.twitter.com/GKAKvqMMEY

— Amy Chozick (@amychozick) April 25, 2018

The modern media environment

Some of Chozick’s most compelling material is when she writes about the struggle to cover the news in the modern media environment.

In a time where most events are captured and live streamed via a smartphone and news tidbits are magnified times ten on Twitter, Chozick writes “the masters of Snapchat and Vine and Twitter and Periscope had become the new ‘heavies’” of the campaign coverage teams.

“Hillary looked at her ’16 press corps and thought we were hopelessly young and driven entirely by clicks and the financial demands on our struggling news outlets,” she wrote.

She also addressed a phenomenon that gained a lot of attention during the 2016 campaign – that the press team covering Clinton was composed mainly of women, including herself.

But, she notes, Clinton didn’t enjoy that dynamic.

“The thing about a mostly female press corps was that Hillary likes men,” Chozick writes. “She told aides she knew women reporters would be harder on her. We’d be jealous and catty and more spiteful than men.”

Chozick, who covered the 2008 Democratic primary for the Wall Street Journal, constantly compared that contest and the 2016 race in her book.

Her observations of how coverage changed in eight years are telling.

“By 2016, so much about the trail had changed. At least back then the ‘traveling press secretary’ actually traveled with the press,” she wrote. “This didn’t seem like a radical concept until 2016 when on most days not a single person authorized to speak for the Clinton campaign ever traveled with us.”

She also addressed the struggle to get close to the candidate, who was guarded by nature and guarded by a wall of aides and Secret Service.

“On a typical day, we’d spend 18 hours on the bus only to set eyes on Hillary from the back of a packed gymnasium or as a flash of blonde disappearing behind a van door held open by a bulky Secret Service agent.”

Email controversy

The Clinton email controversy: It became a single phrase – and not the campaign phrase the Clinton team wanted – that grouped together several scandals: Clinton’s use of a private email server as secretary of state; campaign manager John Podesta getting his email hacked, and the Russians hacking the Democratic National Committee.

The story about Clinton’s email server wouldn’t “go away” in the summer of 2016, Chozick notes, as Team Clinton was feeling the pressure from Bernie Sanders, who was gaining traction among disenfranchised voters.

Chozick rejected the Clinton campaign’s argument that this wasn’t a story but the author had more mixed feelings on covering the emails hacked from Podesta and the DNC.

Early on “the Russian meddling subplot still seemed far-fetched,” she notes but as the controversy grew, she tallied her own part in it – that she co-wrote six stories and one blog post off the hacked emails for the Times.

But, in retrospect, “I didn’t argue that it appeared the emails were stolen by a hostile foreign government that had staged an attack on our electoral system,” she writes. “I didn’t push to hold off on publishing them until we could have a less harried discussion. I didn’t raise the possibility that we’d become puppets in Putin’s shadowy campaign.”

Chozick also addressed her regrets when she appeared on ABC’s “This Week” this past Sunday.

“After the election, it really kept me up at night to think that I did exactly what Russian hackers wanted me to – we all did, by covering those Podesta emails we became, as my newspaper said, de facto instruments for Russian intelligence,” she said.

Nick Confessore, a reporter for the New York Times who also wrote about the emails, tweeted his opinion about the coverage.

“The e-mails revealed information that illuminated our understanding of Clinton, her political and financial relationships, her struggles to find a central message, the factionalism that undermined her campaign operation,” he said in defense of the stories.

“Perhaps not every story we published about the e-mails met the standard of newsworthiness. But I think almost all of them did. Virtually every news organization in America made the judgment we did about news value and the public interest, probably for similar reasons.”

As a former cubicle-mate of @amychozick and an author or co-author on some of the @nytimes coverage of the hacked Podesta and DNC e-mails, I have a different view of our paper's decision to publish stories based on those e-mails.

— Nick Confessore (@nickconfessore) April 22, 2018

Election night

For a book about Hillary Clinton, there’s not a lot of insight into who Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton is.

That’s understandable given the protective wall that Chozick describes surrounding the candidate – a cadre of aides whose main job is to make Clinton look good and protect her from any incidents that could go viral.

The most insightful tidbit about Clinton comes this story about Election Night, when Chozick describes Clinton’s reaction to the news she lost to Trump: “I knew it. I knew this would happen to me,” she quotes Clinton as saying. “They were never going to let me be president."