How Buffalo shooting victim's son shields his ailing father from tragedy

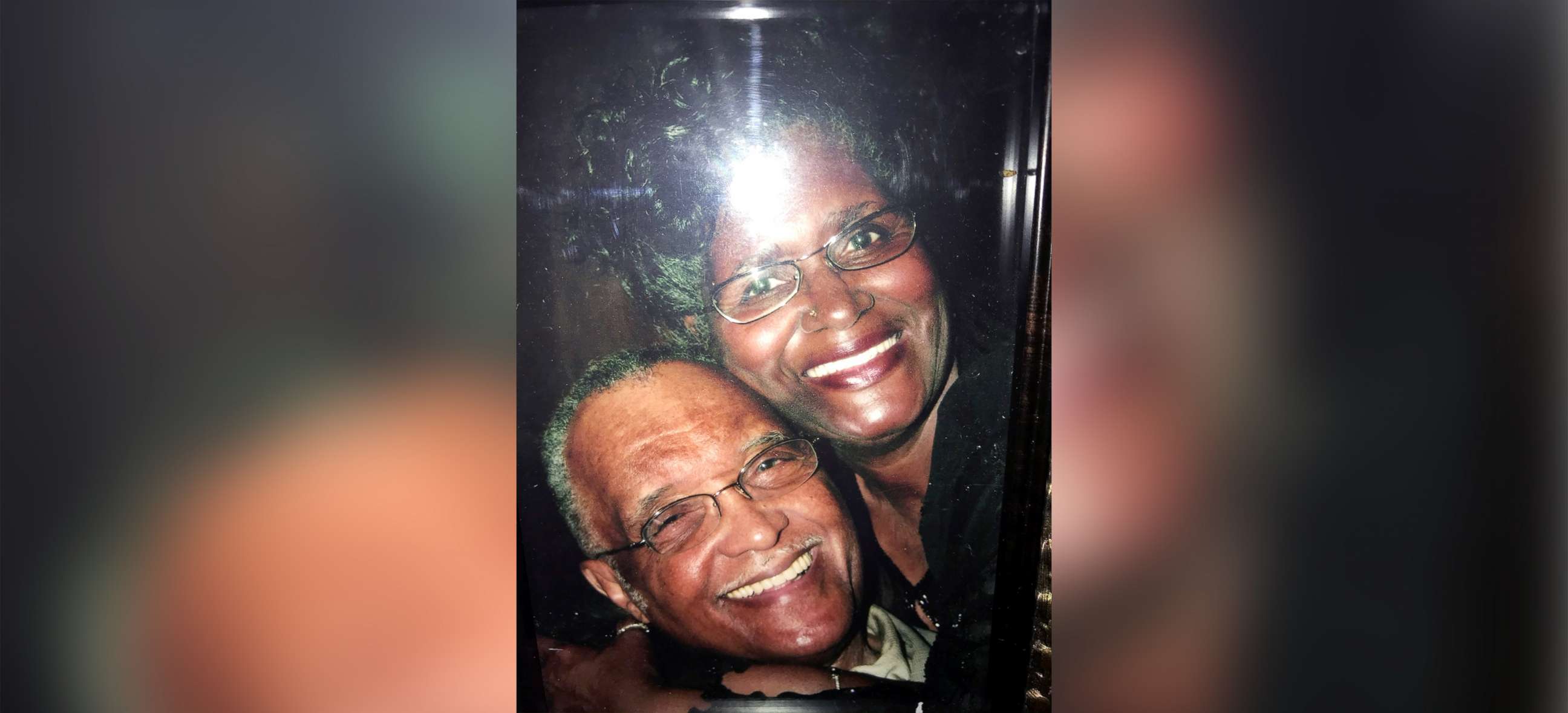

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- More than four months after 10 Black people were fatally shot in a Buffalo grocery store allegedly by a self-proclaimed white supremacist, Garnell Whitfield Jr., who lost his mother in that shooting, wrestles with pangs of grief and anger.

But amid the roller coaster of emotions, one thing gives him a modicum of relief -- knowing his father appears to remain unaware that among those killed was his wife of nearly seven decades.

At age 88, Garnell W. Whitfield Sr. lives in a nursing home just blocks from where his wife, Ruth Whitfield, was gunned down on May 14 in a Tops supermarket in the Cold Springs neighborhood of East Buffalo. He suffers from dementia, according to his son.

"In some ways, my father's illness keeps him safe from going through what we go through every day because we can't forget," Whitfield Jr. told ABC News. "I thank God that he doesn't because that allows him, probably, to go on."

Whitfield Jr., a retired Buffalo fire commissioner, said he, his brother and two sisters are now attempting to take their mother's place, trying to care for their father "in the manner that our mom would want us to."

He said his father is unable to have conversations, explaining, "We communicate with him through our eyes."

"We just don't want him to see us crying," the 65-year-old Whitfield said.

With the help of his family, the senior Whitfield attended the funeral of his wife, who at age 86 was the oldest victim of the massacre.

"We know that he misses her," Whitfield said of his father. "We don't know if he understands that she's never coming back."

A 67-year love story

Ruth and Garnell Whitfield Sr. were originally from the South. He hailed from Alabama and Nashville, Tennessee; she was from Mississippi. The couple met in Buffalo and married in 1955.

Whitfield Sr. worked multiple jobs, enabling his wife to be a stay-at-home mom, the son said. He said his father eventually landed a job at the Ford stamping plant in Buffalo, working his way from the assembly line to electrician.

"We were considered like the Partridge family, or the Waltons or... the Cleavers," Whitfield Jr. told ABC News. "We were a traditional family. My mom and dad were there and the kids. So, we benefited from that. We were very close."

For part of his childhood, his family lived at the Ellicott Mall public housing development in Buffalo before moving into a home on the East Side of the city in the 1960s.

Whitfield said his mother was the rock of the family, who attended all his Little League and football games, and practices.

"She was very serious about our education, very serious about us behaving in a manner that was respectful of others," Whitfield said.

He said his father retired in the mid-1990s after working at Ford for 34 years. His parents moved to New Jersey and then to Burbank, California. When Whitfield Sr.'s health started to decline, they moved back to Buffalo around 2012 to be close to family, the couple's son said.

Within two years of returning to Buffalo, Whitfield Sr., was showing signs of dementia.

He moved into a nursing home eight years ago, his son said.

"She was his caretaker. She was his advocate," Whitfield Jr. said of his mother. "She was responsible for my dad still being alive today."

Ruth Whitfield, he said, was meticulous in the way she cared for his father, laundering and ironing his clothes daily.

"Whatever needed to be done to maintain his quality of life she did for him," her son said.

'A large part of my life is gone forever'

Whitfield said his fondest memory of his mother is his last. In her final days, he spent time with her building a raised garden, a belated Mother's Day present he said he finished the day before her death.

He said he and his wife ran an errand on May 14 and on their way home, his sister-in-law called to tell him of a shooting that had just occurred at the Tops market in East Buffalo. He said his mother often shopped at the store after visiting his father.

"I called my mom, she didn't answer. I called her sister. She didn't answer. Some time passed, I called again. No answer," Whitfield said.

Increasingly concerned, he said he drove to the Tops store.

From the cordoned-off perimeter, he said he could just make out the top of his mother's 2020 black Hyundai Elantra parked in the first accessible space near the store's front door. He said a law enforcement officer confirmed it was her vehicle, noting his mother displayed a Buffalo Bills' cap and thrift-store knickknacks in the dashboard along handwritten notes, including one reading, "God's my co-pilot."

Still, Whitfield said he didn't know if his mother was among the dead or taken with a group of survivors to police headquarters for a debriefing.

Whitfield, who, after retiring from the Buffalo Fire Department in 2017 served as assistant commissioner of Homeland Security for the state of New York until 2019, said a detective agreed to enter the store to confirm if his mother was among those killed, but needed to know what she was wearing. Whitfield asked his father's nursing home to review security video showing how his mother was dressed that morning, enabling the detective to identify her body.

As a firefighter, Whitfield said he was trained to compartmentalize his grief in order to focus on the mission at hand.

"But this was my mother. It wasn't like what we're trained for," he said. "It was about realizing that my life is, to some degree, over, that a large part of my life is gone forever."

'I'm not winning'

The suspected gunman, 19-year-old Payton Gendron, is accused of planning the massacre for months -- including previously traveling to the store, a more than three-hour drive from his home in Conklin, New York -- to scout the layout and count the number of Black people present, according to federal prosecutors.

Gendron has been charged in federal and state courts with multiple counts of murder and hate crimes. He has pleaded not guilty in both cases.

"I've been subjected to racism and bigotry my whole life. And I always knew that it wasn’t me. I wasn’t the one with the problem. I wasn’t less than," Whitfield said, citing values his parents instilled in him and his siblings. "So, to have this guy do this to my mother, and do this to other people… to live in America doesn’t feel good."

His voice cracking with emotion, he added, "My mother and father protected us and kept us safe, allowed us to grow up. I wasn't able to do that for my mother."

In the weeks and months since the deadly rampage, Whitfield said his emotions have ranged from profound sadness to being "mad as hell."

"I'm trying very hard not to be hateful. I'm trying very hard not to be negative. But I'm not winning," Whitfield said.

He said he is trying to channel his emotions into something positive, speaking out against white supremacy and the country's epidemic of gun violence.

In June, he testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Putting members of the panel on the spot, he told them that if they aren't willing to confront white supremacy and the domestic terrorism it inspires, "you should yield your positions of authority and influence to others that are willing to lead on this issue."

Whitfield Jr. told ABC News he plans to spend the rest of his life "trying to live as I was raised."

He said he still believes there are "way more good people than bad," but added many good people are reluctant to speak out about racism because they want to get along. He conceded that he, too, contributed to the problem by failing to speak up about racism and white supremacy until now.

"Before my mom, I wasn’t an activist, I wasn’t out here talking about white supremacy," Whitfield said. "I’m not excusing myself, but I’m not going to continue to be part of the problem."