Bolton emerges as impeachment trial wild-card, putting pressure on GOP to allow witnesses: ANALYSIS

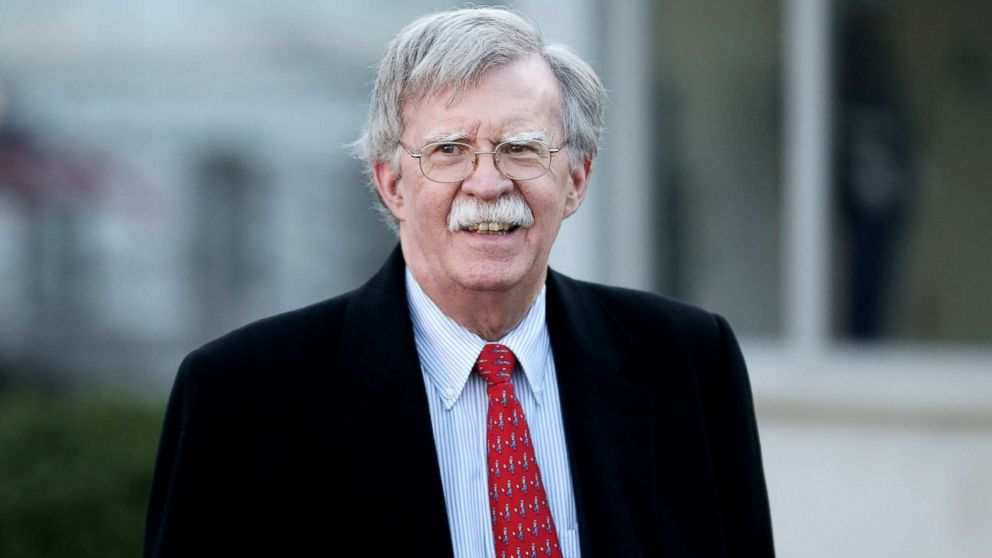

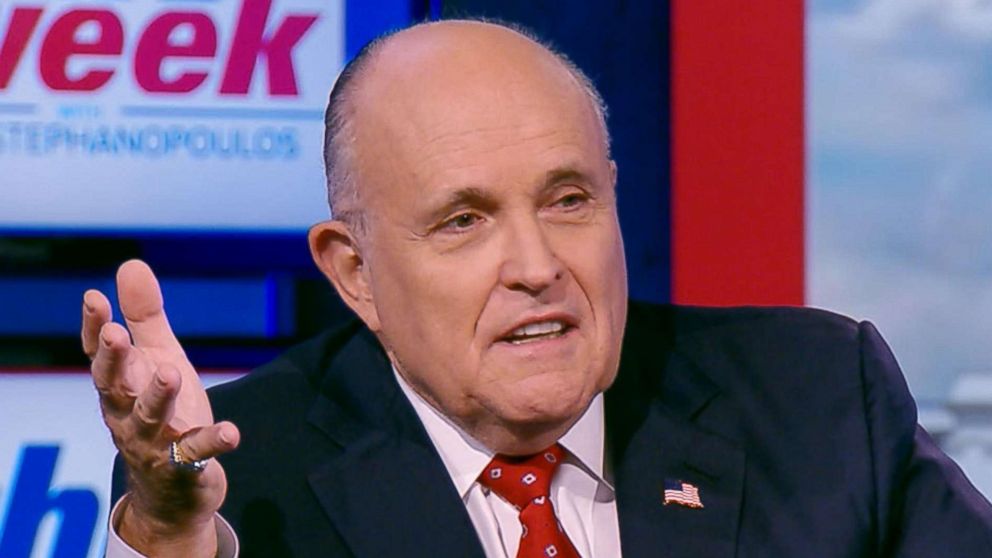

John Bolton privately called Rudy Giuliani a “hand grenade,” compared Giuliani’s dealings in Ukraine to a “drug deal” being cooked up inside the White House, and repeatedly directed his staff to report their concerns to legal counsel.

He also is one of the few people – besides President Donald Trump himself -- who can probably answer the million-dollar question implied in a July 25 phone call to Ukraine’s president but left unresolved by the weeks-long House impeachment inquiry: Did Trump hold almost $400 million in military assistance for Ukraine because of he was skeptical of its anti-corruption efforts? Or was the president waiting to hear Ukraine announce the investigation he wanted into Democrat Joe Biden?

Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, now says he’s willing to testify before the Senate – changing the political calculus in what’s become a game of chicken between Democrats and Republicans on a pending impeachment trial and emerging as the first potential wild-card in the upcoming proceedings.

Bolton’s unexpected offer to testify puts new pressure on Republicans to agree to hear from witnesses in the trial. Senate GOP Leader Mitch McConnell has so far rebuffed the idea in favor of a speedy trial expected to exonerate the president.

McConnell remained unmoved Monday.

“The Senate does not just bob along on the currents of every news cycle,” he told his colleagues on the Senate floor shortly after Bolton’s announcement and advising against allowing Democrats to treat the trial as a “political toy.”

But other Republicans signaled that they wouldn’t stand in the way of Bolton testifying – a move that could crack open the trial to other witnesses testimony and demands for fresh documents. Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer said he would try to force a vote on calling Bolton and others to testify.

Because of Senate rules and the 53-47 party split, Democrats need only four Republicans to join them in supporting a motion for witnesses or to subpoena documents. That narrow split has put all eyes on more moderate or vulnerable Republicans, like Sens. Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Mitt Romney of Utah and Cory Gardner of Colorado.

“Now, it’s up to every senator ... every senator will have a say – which of the two of us wins out? Will we have a fair trial or a cover-up?” Schumer, D-N.Y., said Monday.

While it’s considered highly unlikely that enough Republicans will break from their party to oust Trump – two thirds of the Senate would be needed to remove the president from office – only 51 votes are needed to demand witnesses or documents.

“When the time comes, if 51 senators want to hear Ambassador Bolton, I think that’s fine,” said Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas.

“My guess is this could help the president as much as anything because what I think Bolton could say is that this is as much a disagreement over the way foreign policy is being conducted. There’s no crime being charged,” Cornyn added.

Romney, the Utah Republican and Trump’s former political opponent, said Monday, “Assuming there is a Senate trial, I would like to hear from John Bolton.”

“I’d like to hear what John Bolton has to say. He has some firsthand information. And I think it’d be helpful to be able to hear it," he told reporters. As for supporting a subpoena, Romney said,“The process, I’m not sure of at this stage.”

Bolton has emerged as one of the most intriguing characters in the impeachment saga. Known for his extreme viewpoints on national security foreign policy – he has long advocated for “regime change” in Iran, which critics say is akin to declaring war on the Islamic nation – Trump last September referred to Bolton as “Mr. Tough Guy” and said he asked him to resign over some “very big mistakes.”

"He wasn't getting along with people in the administration that I consider very important," Trump said at the time.

While Bolton had been known to clash with other administration officials, including Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, unknown at the time was the extent to which the then-national security adviser was fending off an effort by Trump’s personal friend and attorney, Rudy Giuliani, to pressure Ukraine to investigate Biden and Biden’s son, Hunter.

Following a meeting with high-level diplomats from Ukraine at the White House, Bolton’s aide Fiona Hill said he told her to relay a message on his behalf to White House legal counsel.

“I am not part of whatever drug deal Sondland and (acting White House Chief of Staff Mick) Mulvaney are cooking up,” Hill testified before the House last fall.

Hill also testified to raising her objections to Bolton about a “smear campaign” launched by Giuliani targeting Marie Yovanovitch, the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine at the time. Hill said she asked Bolton if there was anything they could do.

Bolton, "basically indicated with body language that there was nothing much that we could do about it," Hill testified. "And he then, in the course of that discussion, he said, that Rudy Giuliani was a hand grenade that was going to blow everybody up."

Around the same time Bolton stepped down – he insisted he resigned on his own accord and was never asked to leave – House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff, D-Calif., was pressing the administration for details about a whistleblower complaint on Ukraine. It remains unclear whether Bolton’s decision to leave was in any way tied to his opposition to Giuliani’s efforts in Ukraine.

Bolton was never subpoenaed by House Democrats. The White House declined to cooperate with the House inquiry, and while some aides like Hill agreed to testify anyway, Trump’s top advisers like Mulvaney and Vice President Mike Pence ignored congressional requests.

House Democrats opted to move ahead with their inquiry and vote, rather than wait for the courts to weigh in on whether Trump’s top aides should be forced to comply with testimony.

Now the question becomes whether the Senate can force the issue again, particularly as new evidence trickles out. Last week, new emails emerged from a top Pentagon budget official and the White House budget office that suggested the president personally retained the hold on aid despite repeated warnings from the Pentagon that withholding aid was potentially illegal.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has put off handing over articles of impeachment – a necessary procedural move to kick off a Senate trial – until more is known about how the Senate trial will be structured. The move baffled Republicans who said they were happy to drop the matter and move on. But it also frustrated Trump and his allies who are eager for a favorable trial for Trump by the Republican majority.

But the question now is whether vulnerable or moderate GOP senators will side with Democrats without a procedural agreement reached by McConnell and Schumer.

Collins said she still hopes the two sides can reach an agreement on the rules.

On Bolton, Collins – who is up for re-election this year – said: “There are a number of witnesses that may well be appropriate … of which he would certainly be one.”

ABC News' Trish Turner and Mariam Khan contributed to this report.