In 'babysitting while black' video, black dads see echoes of reality they know all too well

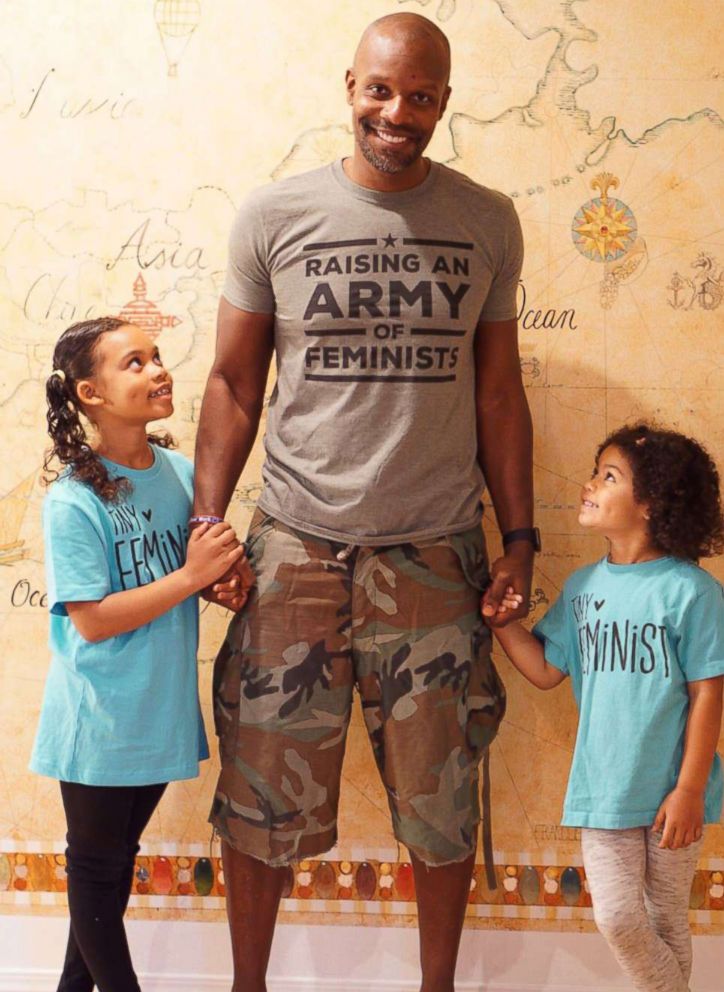

It was December 2013 and a sleep-deprived Doyin Richards was Christmas shopping with his young daughters at a mall in Los Angeles when he said he noticed a woman following him.

Richards said as he moved from store to store with his fussy girls -- ages 2 and 5 months old -- for the next 15 minutes, the woman did, too.

"When I finally got to a bench and tried to console the kids, who were crying for various reasons, she walked by a couple times," Richards, 43, told ABC News. "Then she was like, 'Excuse me,' and I thought she was going to comfort me, like, 'I get it, man, it's hard being a new parent and stuff.'

"Instead, she said, 'I just want to make sure, are those your children?'" he said of the woman, who appeared to be white.

It was a lesson I taught my son: 'They will judge you by your skin, even before anything else, even before they get to know you.'

Richards, who is black, said he was floored -- and furious.

"I'm like, 'Yes, they are my children.' And she said, 'Oh, I'm so sorry, there are so many stories of kids being snatched and I didn't mean to offend,' and she was so incredibly apologetic, but I'm not having it," Richards said. "Both kids were crying. They were both having a meltdown, and instead of comforting me, or saying, 'It's ok, I get it, I've had kids before,' it was like, 'These kids are distressed and they're lighter than him, he must be trying to take them away from their mother.'"

Richards never forgot that moment. That's why when video surfaced this week of a white woman calling the police on a black man who was babysitting white children, Richards was outraged -- but not surprised.

For black dads across the country, that video captured two realities many say they have faced at some point: the assumption that black men don't take care of children and that they can have the police called on them for simply going about their daily lives.

The video is the latest in recent months that all captured white people calling police on people of color for selling bottled water, barbecuing and sitting in a Starbucks, among other everyday actions.

It's difficult to determine the extent to which race was a factor in the calls, though nearly all of the people who called police said they did so out of a sense of duty, not because those involved were black.

Still, the person’s race was mentioned in some of the calls. And the backlash on social media was swift, with many saying the calls wouldn’t have been placed about white people doing the same things.

Corey Lewis, the owner of a babysitting and mentoring business in Georgia, was watching two 6- and 10-year-old children on Sunday when an unidentified white woman approached them in a Walmart parking lot.

"She pulled up to my vehicle and asked if the kids were all right," Lewis told "Good Morning America" Wednesday. "I responded with, 'Why wouldn't they be?'"

"She then said, 'Things look weird,' and then she drove off," Lewis said.

After he left, he said he realized that she was following them.

After Lewis and the children arrived home, a police officer came in response to the woman's call to 911. That was when the officer called the children's parents, David Parker and Dana Mango.

"We were at dinner, and I saw that Mr. Lewis had called," Mango told "Good Morning America." "I called back and a police officer answered the phone. The police officer was trying to explain that he was there with my kids and that they were ok, but he wanted to confirm that I had given permission to Mr. Lewis to be with them."

"It truly took me several minutes to believe that it was real. I was just in a state of disbelief," Mango said.

But for many black fathers, disbelief wasn't one of the many emotions they felt after watching Lewis' video.

For me, the largest learning curve in my life was how to be a big influence and a caring dad to my daughter.

"Every day, we as black men are guilty until proven innocent," Richards said. "We never get the benefit of the doubt: like maybe those are his kids, or maybe that black man is babysitting those white kids. It's always, 'Oh, there's something nefarious going on.'"

Growing up in the Sandtown neighborhood of Baltimore, Antoine Bennett, 47, said he didn't see much of his dad, even though he lived just down the street. When it came time to raise his own daughter, Antonia, he was determined to be a big part of her life.

The two are now very close.

"I'm a very comical person and I like comedy and I like to laugh, and I see that in her, how much she is very much a part of me," Bennett told ABC News. "I love the fact that she loves being a Bennett."

But, he said, when people see the two of them together, they assume Antonia, 10, is his granddaughter or niece.

"Many times, when they see a black man with a little child, they think it's probably their niece, nephew or stepchild, that there's no real active role in society's definition of black male fathers," Bennett said. "Of course, we take our children to the mall, of course, we will take them to the movies, of course, we will take them out to dinner. So the child you see us with is often our biological child and it's our intention to spend quality time with our child."

Those assumptions that black dads are never around are hurtful, Bennett said, and are part of what motivated him to help found Men of Valuable Action, a support organization for fathers in his neighborhood.

What it is to be a black man raising kids is very similar to what it is like to be a white man raising kids, or a white woman raising kids.

"It pierces my heart, and it's almost generational, if we're not careful," Bennett said. "For me, the largest learning curve in my life was how to be a big influence and a caring dad to my daughter. My father wasn't active at all in my life, and I lived down the street from him.

"In terms of how to take care of a child, to put the child first and all that, it was all learning for me, because my father didn't demonstrate as well as he should have, or I feel I deserved," he added.

Damon Jones, 50, said that as a single dad, his son lived with him from the time he was 9 until he graduated high school. He said he was entitled to receive child support from his son's mother, but every time he went to collect it, the people working in the office assumed he was there because he hadn't paid.

"It was always assumed as black man that I was paying child support until I had to point to the papers and say, 'No, I'm receiving it. I'm the one receiving child support.' The perception is that black males are not even taking care of their children," Jones told ABC News. "Those stereotypes are even in the institutions that black males cannot be fathers."

Richards said he has confronted those stereotypes many times. Once, when he was with his older daughter at a Los Angeles Starbucks, he said a white woman approached him to say how cute she was.

"And then she said to me, when she was about to leave, 'You know, um, no offense, but it's not very often I see black men out with their children. No matter what happens, I hope you stay in that little girl's life,'" Richards remembered.

"I had nothing in my mental Rolodex to combat that, so I was just like, 'Thanks, I will,' and she left," Richards said. "Then, when I was walking home and pushing Emi in the stroller, I was like, That's messed up, man. She wouldn't say that ... to the white dad down the street, but she would say it to me. And where is that coming from?"

If they get to the point that they are going to call the police on somebody doing something legal, and the only reason they're calling is because he's black, they should be brought up on some type of charges, even if it's filing a false report.

Those negative ideas about black men have an impact on their children as well, fathers say. Research published by the American Psychological Association in 2017 found that "people have a tendency to perceive black men as larger and more threatening than similarly sized white men," and that such a bias exists even among black people.

That perception affects how black children move in the world, parents say.

"We always had the talk with our children, how to act in public places, how to carry ourselves, especially as black males," Jones said.

I've been followed in stores, I've been pulled over because I have a nice car. It's sad, but it's a reality black men face.

Jones said that when he took his then-teenage son to shop for sneakers near their home in Westchester County, New York, in 2003, mall security guards followed them around. Jones, a former law enforcement officer, eventually decided to show them his badge.

"Me being law enforcement, I had to turn around and say, 'Look, why are you following me?'" Jones said. "I'm law enforcement, I know when I'm being tailed and I know when someone is watching me. Unfortunately, sometimes, we have to pull out a badge or identification to show we're law enforcement to get them to walk away. My wife is a detective and she has experienced the same thing shopping for clothes."

Jones said he used the moment in the mall to teach his son a sad reality: that as black men, they can be viewed as threats even when they are going about their day-to-day lives.

"It was a lesson I taught him: 'They will judge you by your skin, even before anything else, even before they get to know you,'" Jones said.

"I've been followed in stores, I've been pulled over because I have a nice car," he added. "It's sad, but it's a reality back men face. And we have been facing it since the Emancipation Proclamation. Just now, it's talked about more because of social media."

Jones, who is now the New York representative for Blacks in Law Enforcement of America, said there must be clearer penalties for people who call the police on black people for simply existing.

"If they get to the point that they are going to call the police on somebody doing something legal, and the only reason they're calling is because he's black, they should be brought up on some type of charges, even if it's filing a false report," Jones said. "Something that simple, that's the only way you're going to nip it in the bud, if they're held accountable for that."

Richards agreed, adding that there needs to be a shift in the mentality some white people have toward police.

"Law enforcement is not your personal valet. They are not customer service for life. They are here to stop crimes and to protect and serve," he said. "Let us live our lives and stop calling the cops on us for simply existing."

It's also about simply reaching out and making a connection, he said.

"What it is to be a black man raising kids is very similar to what it is like to be a white man raising kids, or a white woman raising kids," Richards added. "Be a friend, come up and have a conversation with us."

ABC News' Karma Allen contributed to this report.