'Arab Spring 2.0': What to know about the protests roiling Iraq, Lebanon and the Middle East

Washington, DC & Beirut, Lebanon -- It's been nearly a decade since a Tunisian street vendor set himself on fire -- an act of protest and desperation that culminated in the Arab Spring demonstrations across the Middle East and North Africa. But for millions of citizens in the same countries that saw widespread protests, there has been little improvement, with scant economic opportunities and governments mired in corruption or ruled by strongmen.

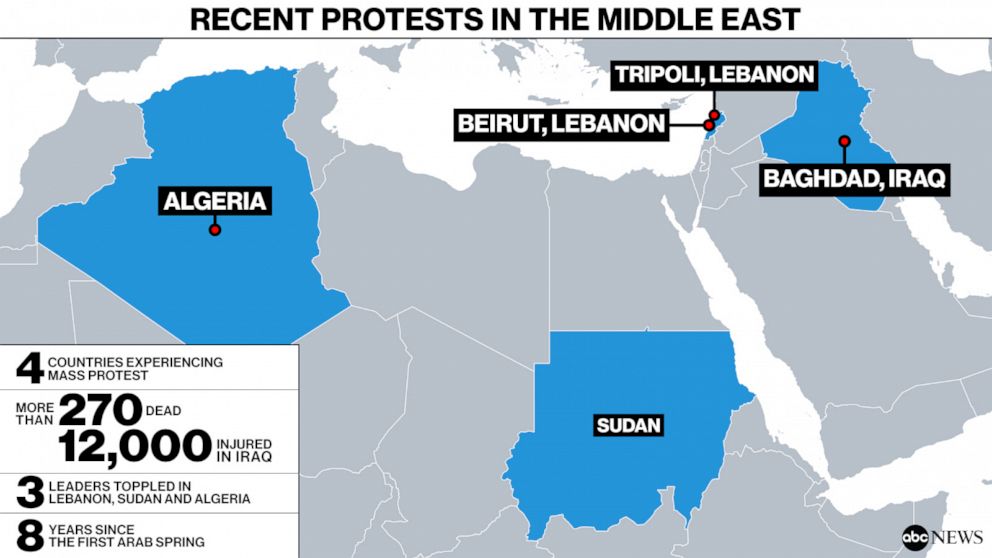

That has ignited a new wave of protests this year, with particularly violent clashes in recent weeks in Lebanon and Iraq, but successful change in Sudan and Algeria as well as successful elections in Tunisia. Here's what you need to know about what some analysts have characterized as Arab Spring 2.0.

What's happening in Lebanon?

Protesters in each country have a unique set of demands, but the central themes have been the same -- calling for changes in government amid a deep distrust of leaders and for economic opportunities amid high levels of corruption and unemployment, especially for young people.

In Lebanon, the demonstrations which began three weeks ago were sparked by dire warnings that the national economy is on the verge of collapse and fears of the state sliding into bankruptcy. Outrage at rampant government corruption has cut across traditional sectarian lines and united young and old alike, from retired people on limited pensions to middle class families with young children and students who see little to no future in their own nation.

Protesters have taken to the streets not just in the capital, Beirut, but other major cities, especially Tripoli in the north, and in towns and villages across the country, for peaceful demonstrations that at times have resembled celebrations, with music and dancing.

Protesters say they're fed up with a government that is rife with sectarian cronyism and closed-door dealings where the political elite grow fat on taxes, fees and no-bid, secret contracts while returning little to no services back to the people. They point to frequent electricity and water cuts, poor internet service and a chronic trash problem that they say is slowly poisoning the environment. They are demanding the government be replaced by technocrats -- people drawn from the large pool of highly educated, non-political experts in Lebanon.

Security forces are increasingly showing signs that they are losing patience with the protesters. On Tuesday morning the Lebanese Army stepped in to open one of the main freeways, arresting a number of protesters to clear them out of the way of cars.

On the whole, Lebanese protests have remained largely peaceful, although last week there fears of wider sectarian clashes after Hezbollah supporters briefly rampaged through the main protest camp in central Beirut.

The demonstrations have succeeded in toppling the government of Prime Minister Saad Hariri, who announced his resignation and that of his cabinet on Oct. 29.

What's happening in Iraq

In Iraq, protesters have been met with a far more violent response. Demonstrations have swept through Baghdad and much of the country's south, with anger fueled by corruption, little opportunity, and the inordinate power wielded by Iran and its militias. Tens of thousands have called for the government to be overthrown and deep reform to be enacted, but security forces and those same armed militias backed by Tehran have responded with deadly force.

More than 270 people have been killed since Iraq's demonstrations began in early October and 12,000 injured, according to estimates by the United Nations.

The UN report attributes at least 16 deaths – and many serious injuries – to demonstrators being struck by tear gas canisters.

"There is no justification for security forces to fire tear gas canisters or sound and flash devices directly at unarmed demonstrators", said Danielle Bell, Chief of the UNAMI Human Rights Office.

Additionally, the UN specifically points to continued efforts by the Iraqi government to suppress media coverage as well as curbing access to the internet. Special Representative Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert added: "We must recognize that in today's digital age, daily life has moved online. A blanket shutdown of internet and social media is not only disruptive to the way people live their lives and do business: it infringes freedom of expression."

The backlash has sparked greater anger at Iran, which maintains strong influence with the government of Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi, a Shiite who has not yet resigned, but may step down if a caretaker government can be formed, according to President Barham Salih.

What's happening elsewhere?

While Iraq and Lebanon have seized the headlines, there were also mass demonstrations in Algeria last Friday, where tens of thousands marched to demand a "new revolution" and oppose the government proposed election next month, according to the BBC. Algeria's longtime President Abdelaziz Bouteflika resigned in April after weeks of protest, but since then protesters have demanded sweeping reform and greater freedoms, arguing that an election next month would not be free or fair under the current system.

Tunisia remains a model for its transition to democracy after the Arab Spring -- the only real success story after protests in 2011. In July, its president, Beji Caid Essebsi, died in office, but a caretaker government peacefully held power until a new president was declared in mid-October following elections.

Protests in Sudan earlier this year toppled longtime strongman President Omar al-Bashir after three decades in power, but didn't stop there. Protesters also took on the military leaders who grabbed control and forced them into an agreement in August to create a power-sharing government and begin a transition to democracy. As recently as Sunday, demonstrators continued to take to the street to demand the disbanding of Bashir's former ruling party and to call for an investigation into violence against the protesters.

What comes next?

Sudan and Algeria may have achieved certain levels of measurable success and are, at least for the time being, on the path to peaceful and successful resolutions that will hand more power over to the people. But for nations like Lebanon and Iraq, despite all the outrage, there is so far very little indication that the latest groundswell of popular dissatisfaction with unpopular leaders will be able to secure any real change.

The leadership in Iraq appears to be secure and confident with its control of the oil wealth and Tehran has already invested too much time and money wooing it as a regional partner to allow it to easily slip away.

As the death toll continues to rise in Iraq, it is becoming clear that the power establishment is not ready to concede without a bloody struggle. The United Nations Mission in Iraq on Monday called the continuing bloodshed in the country "appalling." "The deep frustration of the people should not be underestimated or misread," the mission said in a statement.

"Violence only breeds violence and peaceful protesters must be protected. It is time for national dialogue," the mission added in the statement.

In Lebanon, after nearly three weeks of daily protest, the cracks in popular support are beginning to show. The main strategy has been to block off major roadways to disrupt normal life and paralyze the country. It's the only way, protesters reason, to really frighten those in power by making life unbearable for everyone.

Yet, after 20 days of schools, banks and universities remaining mostly shut, shopkeepers losing money hand-over-fist and people struggling to get to their jobs, the silent majority may eventually redirect its anger from the government to the activists.

With time running out, protesters are feeling the pressure, yet they are wary of being sidelined and ignored by government ministers until momentum for overturning the corrupt status quo dies down. They have seen it happen to every Lebanese protest movement over the last 30 years and they are determined this time to replace the entire roster of cabinet ministers and established politicians before their voices can be quashed.

The most popular chant heard at the Lebanese roadblocks is, "All of them means all of them."