Andrew Yang calls himself 'Mr. Job Creator.' But critics say his numbers don’t add up

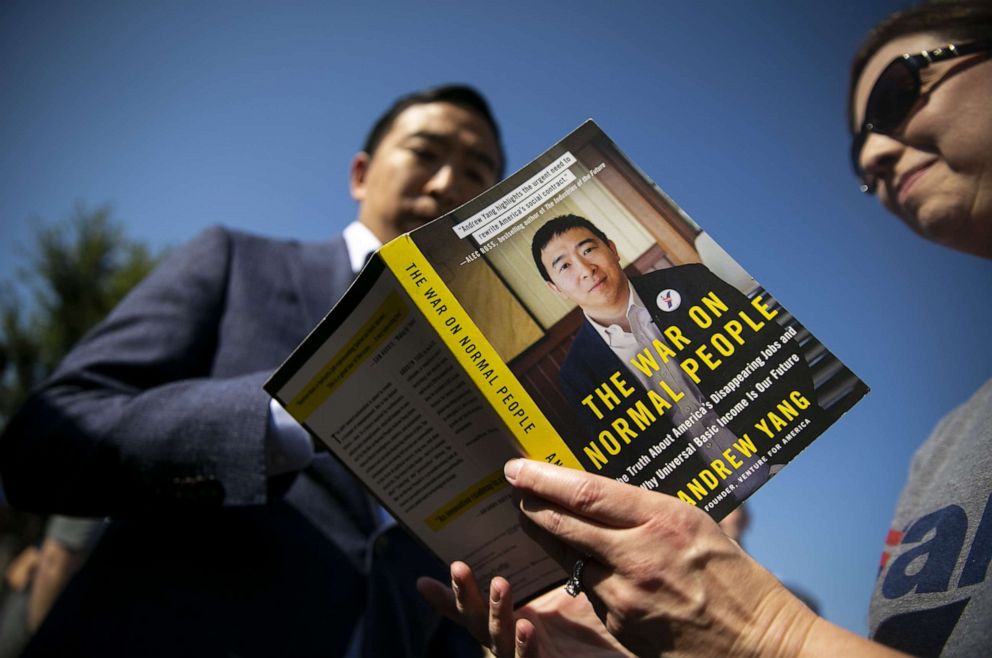

At a small event in Londonderry, New Hampshire, last week, Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang was talking about one of his key qualifications to be president of the United States -- his track record of creating "thousands of jobs."

"So Trump wins. I'm like, 'Oh, my gosh.' You know, here I am, Mr. Job Creator. Getting awards and accolades," Yang told the crowd. "And I feel like I'm pouring water into a bathtub that has a giant hole ripped in the bottom."

Yang's claim to the title rests largely on Venture for America, an innovative nonprofit he launched in 2011 with a clear objective: Create 100,000 new jobs by 2025 by placing top college graduates at startups across the country. These young hires, or "VFA Fellows," would complete a two-year stint before transitioning out of the program, theoretically armed with the skills to start their own companies and hire their own employees.

Think "Teach for America" for entrepreneurship.

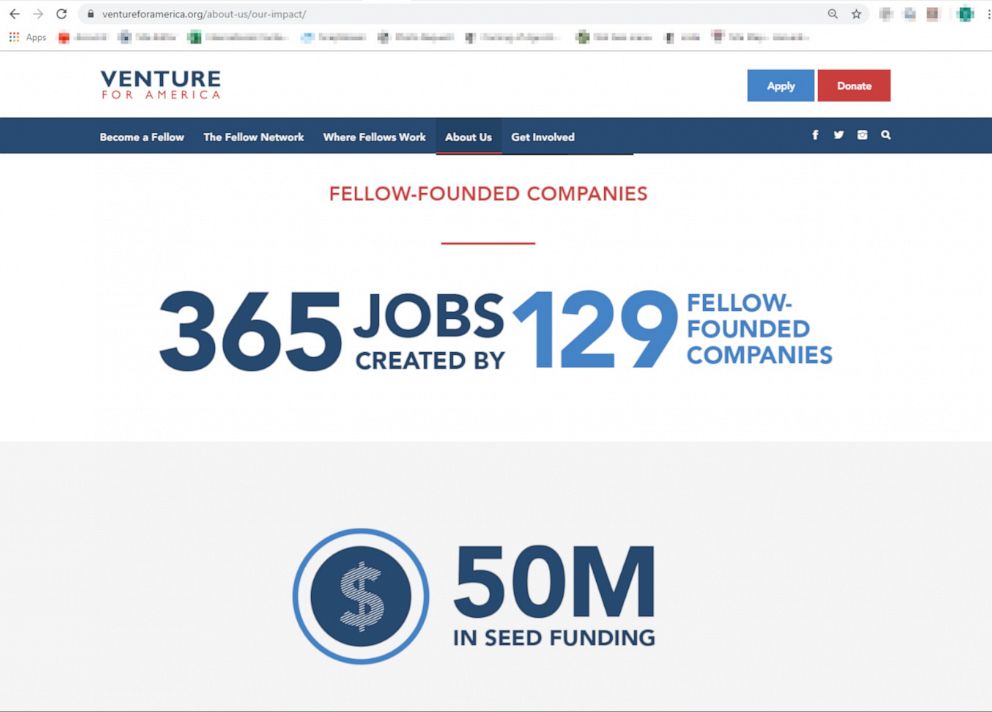

Several economists described the project as a worthy cause, one designed to address a vexing problem, but nearly a decade after its launch, it's clear that -- despite Yang's campaign trail assertions to the contrary -- Venture for America's actual impact has not kept pace with its founder's ambition. Until this week, Venture for America's own website touted just 365 jobs created by 129 fellow-founded companies.

Within a few hours after receiving questions from ABC News, the organization took down the page in question.

Antonia Dean, a Venture for America spokeswoman, told ABC News that the number on their website was out of date. The actual number of jobs created is much higher, she said, though she declined to provide more recent figures. Dean also noted that Venture for America, which is no longer affiliated with Yang, who left more than two years ago, is no longer making job-creation claims as it begins "shifting the way we measure our impact."

But according to Dean, Venture for America’s metrics reflect not only jobs directly created at companies founded by fellows but also jobs created at companies that hosted fellows. Until this week, for example, its website noted that VFA fellows "have contributed to the growth" of more than 450 startups.

That has led some critics to call Venture for America's tally – upon which Yang has bolstered his campaign credentials -- into question.

John Dearie, the president of the Center for American Entrepreneurship, said that method was "misleading."

"Venture for America has a great mission because we know from lots of research in recent years that new businesses account for most net new job creation in the economy, but they also take credit for thousands of jobs created by already existing startups in which VFA fellows are merely embedded to help," Dearie told ABC News. "The embedded fellows might well have made important contributions, but the real credit for the jobs created at those startups should go to the entrepreneurs who took the risk and did the hard work to launch them."

Yang's outsider bid for president will be put to the test by voters in Iowa and New Hampshire in the coming weeks. His campaign has relied heavily on his upbeat personality and a policy agenda that centered on workplace innovation that will create opportunities for those left behind in the modern American economy.

In response to questions from ABC News, the Yang campaign's national press secretary, S.Y. Lee, defended Venture for America's metrics to measure job creation and touted a pair of entrepreneurship honors Yang received from the Obama administration.

"In its first year, VFA trained 40 fellows; by 2017, more than 500 VFA fellows and alumni had launched dozens of companies and helped create thousands of jobs across the country," Lee told ABC News. "The Obama White House even named Yang a Champion of Change in 2012 and a Presidential Ambassador for Global Entrepreneurship in 2015."

Experts say tracking job creation can be a difficult task. According to Barbara Dyer, a senior lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management, job creation can rarely be attributed to one specific thing.

"It's very hard to track job creation in general because there are lots of variables that contribute to it," Dyer told ABC News. "If you are trying to look at the impact of a specific social innovation that is designed to be a catalyst for multiple jobs created, it's very hard to claim that one thing as being the source of it."

Justin McLaughlin, the founder of AirCFO, a Cleveland-based startup that has partnered with Venture for America for years, said he supports the organization's efforts to recruit young employees to his and other businesses. But he disagrees with the method behind the metrics.

"I can't get behind a calculation that attributes our total job growth to hiring a VFA fellow," McLaughlin told ABC News. "At AirCFO, we've had an incredible experience with both our VFA fellows and I firmly stand behind VFA's mission. Both have helped us grow, but no more than other hires we've made."

Annelies Goger, a David M. Rubenstein Fellow in the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program, said tracking job creation as a result of government programs follows a rigorous protocol.

"In government programs, jobs are tracked only through direct placement using wage records, paystubs and similar forms of verification," Goger told ABC News. "Those programs are not allowed to claim that any other jobs at the same company were attributable to the government program."

Venture for America's methods, on the other hand, she said, do not stand up to scrutiny.

"They cannot reliably claim," Goger said, "that the fellowship caused the creation of other jobs at the firm."