Amid COVID-19, moms leaving the workforce could have lasting impact on economy

Katie Morales tried desperately to keep working while also caring for her 7-year-old daughter amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Friends and family [were] driving really long distances to come watch Genevieve for like a week or two weeks or a month at a time,” Morales said. “All so I could keep doing this work that I loved.”

Soon, it became too much for the 33-year-old single mom to handle.

“I used up all my sick days basically in the first six weeks of schools closing, and I think that I did what I had to do,” Morales told “Nightline.”

Before the pandemic, she was working at an animal rescue farm in upstate New York. When schools closed in March, child care became an issue for the working mother.

“If the choice is between continuing to take care of animals and taking care of my daughter, I have to choose my daughter,” Morales said.

Morales made the agonizing decision to quit her dream job and move across the country, back to her hometown in Chino, California, so her mother and grandmother could help with child care.

“It was a very sad day. I really took what I was doing seriously, and I really wanted to be there,” she said.

Morales is one of nearly 2.2 million women who have left the workforce since the pandemic began, according to the National Women’s Law Center. At least one in four women are considering downsizing their careers or leaving the workforce due to challenges created by the pandemic, a study by McKinsey and LeanIn.org found.

“You could say it’s a personal choice, but it doesn't feel like one,” Morales said.

“It’s not just moms,” she added. “It’s my mom and my grandmother. It’s generations back of women and mothers who ended up being affected by this. If I fall, who is going to pick me up? My mom. Just like I would for my daughter.”

Alicia Modestino, a professor at Northeastern University in Boston, said economists are calling the trend of women facing the same decision as Morales a “she-cession.”

“Women are taking the brunt of the labor market damage from COVID-19,” Modestino said. “This is for two reasons. One is because a lot of the industries and occupations that they work in have been hard hit by the pandemic. But the second reason is because of the lack of child care and the disruption that day care and school closures have caused.”

Women ages 25 to 44 are almost three times as likely as men of the same age group to not be working due to child care demands, according to new research from the U.S. Census Bureau and Federal Reserve.

“Even before the pandemic, a lot of the child care fell disproportionately on women,” Modestino said. “They're more likely to be cutting back their hours because of child care. They're doing more at home. They're sleeping less. They're suffering greater psychological distress. And because of this, we're going to see the gender gap widen over time.”

That would cost upward of $700 billion for the U.S. economy in terms of lost productivity -- 3.5% of the GDP, according to Modestino.

Experts say leaving the workforce even for a short time can have a long-term impact on women’s careers.

“A lot of the times we've seen when women take time off from a career, whether it be maternity leave or a year, it takes time to get back into the labor market,” Modestino said. “Right now, the labor market is not great either. And so this is likely to set women back a generation.”

Even women who have kept their jobs and have the flexibility to work from home are feeling overwhelmed.

Arika Beachy, a single mom, is doing her best with her 6-year-old son, Teddy. She's been working at a housing and human rights organization from home, out of her one-bedroom New York City apartment.

At 8 a.m., her son logs onto school online. She said they share a workspace in their modest home.

“It’s challenging for sure. He needs a lot of support and direction,” Beachy said.

During their day, they’re just feet apart. When her son’s headphones don’t work, she must work while listening to his lessons.

In addition to juggling remote school and work, Beachy has to cope with increased household responsibilities. Cooking and cleaning consume hours of her day.

“One [of the] biggest issues are dishes,” she said. “It’s one of the activities I’m up into the all hours of the morning, doing almost on a daily basis, because I don’t have a dishwasher -- just my two hands.”

Holly Oakes has been working from home since March, balancing her demanding full-time job with a sportswear company in Portland, Oregon, and helping her two kids, ages 10 and 12, with their remote learning.

She wakes up just after 5:30 a.m.

“I usually get an hour or so of uninterrupted work time,” she said. “There is also the fun fact that my son is in band, and they have to do it virtually.”

Oakes’ husband works from home, too, but she says she bears the brunt of child care.

“I feel like we're doing so much,” she said. “I kind of liken it to, you're trying to plug holes in a sinking boat, and there's just so many that you can't plug all of them. I definitely feel like I'm failing in all areas.”

Her job has been supportive, but it’s still taking a toll.

“I recognize how lucky I am that I can work from home, and I don't have to go into an office every day or into the field every day,” she said. “I also have a partner that I'm working with. I can't imagine what it would be like being a single parent, having to go into the field.”

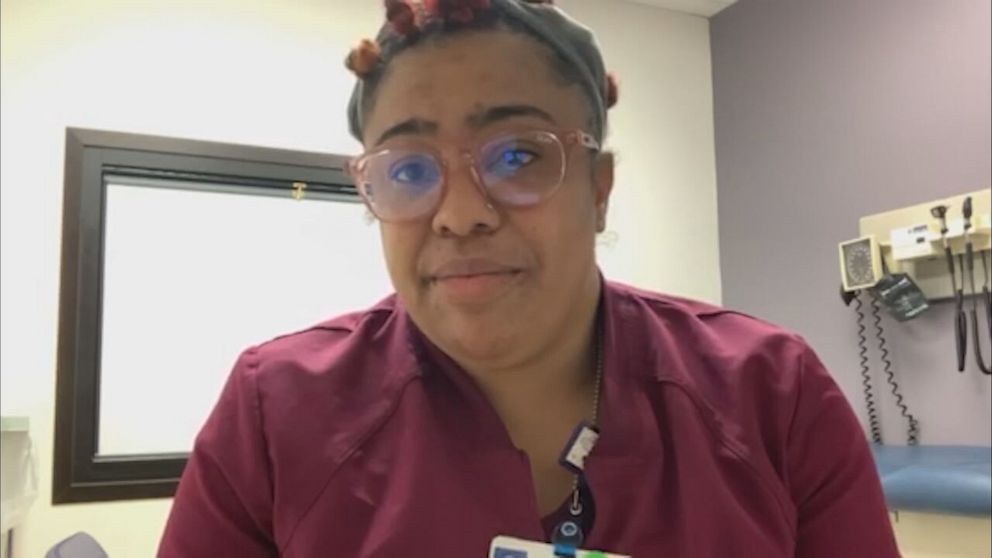

Some single mothers like Angel Marino, a certified medical assistant in Detroit, have no choice but to keep reporting for her job at the hospital.

“Even in this time right now with this COVID-19, I can't afford not to work,” Marino told “Nightline.”

Women of color have been hit hardest by the pandemic. Since February, the number of Hispanic women in the U.S. labor force has fallen nearly 7%, the number of Black women declined 5.6% and the number of white women fell nearly 3%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Many of those individuals are working in-person jobs,” Modestino said. “There's no working from home there. There's no shifting your hours around. And they also have less access to backup child care. So they're less likely to have a nanny or a babysitter or someone else that they can turn to to watch their kids so that they can get to work.”

Marino said it’s been difficult since the pandemic began in March, but she is thankful to have a team that’s “very resourceful” and has tried to help her get through her struggles.

“They understand I'm not alone in this,” she said. But, “they also need people to show up to work, so it's been a challenge."

Even before the pandemic, Marino said finances were tight for her and her three children. They made their own hand sanitizers and their own masks. She said she never wants them to be homeless like when she was a child, after her mother died.

“I want my kids to have stability,” Marino said.

In the spring, while her workplace was under siege with COVID-19 patients, child care was a hard problem to solve.

At that time, her children were in a free day care for essential workers, funded for a time by philanthropies. Later, they went to an in-person learning pod at their school, but that will soon close on Dec. 4 due to rising COVID-19 cases.

“I am just going to have to figure it out this week, what I am going to do,” Marino said. “I don't have much support. My mom died when I was 2. My grandmother, her mother, died of cancer a few years ago."

“You fight so hard to get the job and stuff and get somewhere, and then you get it," she continued. "The choice of working or kids shouldn't be a choice. I want to be the best mom I can be”

But she has a hard-won resilience.

“We can do this,” Marino said. “I was born to cross mountains.”

Modestino said for working moms like her to continue to hold themselves to a pre-pandemic standard is "ludicrous."

"It's always going to be moms picking up the loose ends and tying them for people," she said. "Give yourself permission to leave some stuff untied."

In California, Morales said her daughter is doing virtual learning, and she hopes she can learn from this time of struggle.

“I want her to be scrappy,” she said. “I don’t have enough power to change how the world operates, but I can only show my daughter how we operate within the world.”