America's national parks face existential crisis over race

As millions of Americans escape home quarantine to the great outdoors this summer, they'll venture into parks, campgrounds and forest lands that remain stubborn bastions of self-segregation.

"The outdoors and public lands suffer from the same systemic racism that the rest of our society does," said Joel Pannell, associate director of the Sierra Club, which is leading an effort to boost diversity in the wilderness and access to natural spaces.

New government data, shared first with ABC News, shows the country's premier outdoor spaces -- the 419 national parks -- remain overwhelmingly white. Just 23% of visitors to the parks were people of color, the National Park Service found in its most recent 10-year survey; 77% were white. Minorities make up 42% of the U.S. population.

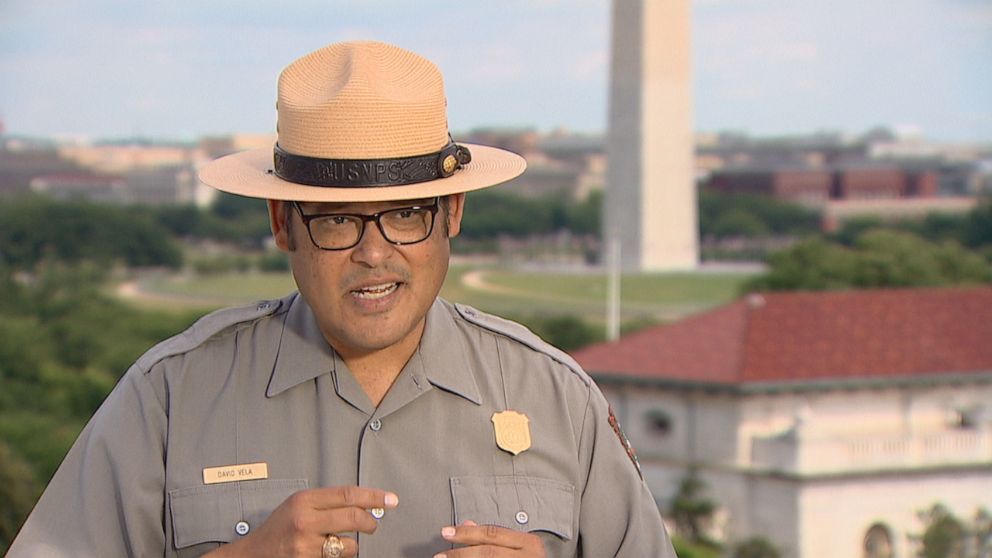

"That tells me that we've got a lot of work to do," said David Vela, acting director of the National Park Service.

The career park administrator, appointed by President Donald Trump to the post in 2017, is the first Latino to lead the agency.

Government officials and environmental advocates agree that the racial disparity in the outdoors is an existential crisis.

"If we don't address this, and we don't see how all these things are interrelated, then we're going to risk losing everything," said Pannell. "You're not going to have public lands to enjoy."

The U.S. Census Bureau projects people of color will be a majority in America by 2044 -- a demographic shift that will impact park attendance and finances. Community advocates say physical and mental health for minority communities is also at risk.

"I feel like nature is a right to everyone, and we should all feel safe enough to experience it," said Lauren Gay, a Tampa, Florida, mother who chronicles her experiences as a woman of color in the wilderness on her blog and podcast "Outdoorsy Diva."

"We need better ways to cope with stress, to cope with some level of trauma. We all have some level, honestly, of PTSD from a lot of the things we've lived through as people of color -- and nature is a way to do that," Gay said.

A not-so-inclusive experience for some

Ambreen Tariq, creator of the "Brown People Camping" social media campaign, learned to camp with her family in Minnesota after they emigrated to the U.S. from India. She now advocates for representation of families like hers and people of color to enjoy the outdoors.

"The future of our country is more and more diverse, ... we're going to have more people of color in this country than white people, but our parks, our green spaces, our conservation spaces, those demographics are remaining white. What does that mean for the future of our land, for environmentalism? We need everyone to experience and then love the land so that they will stay and fight," Tariq said.

"So you think the parks are at risk? Absolutely. The parks are at risk, just like every other natural resource in this country. Land, water, air. These are resources to be preserved. And it not just takes money. It takes people fighting for it," she continued.

Still, racial profiling and stereotyping remain a big concern for Tariq and many people of color in the outdoors.

"When I was a child, I felt like an outsider trying to gain entrance, except now I am American and this is my country," she said.

However, when she camps or hikes as an adult, Tariq said she still faces assumptions that she doesn't belong and a sense of "imposter syndrome" and fear -- even facing questions from rangers about whether she has followed park rules when she doesn't see white visitors asked the same questions.

Danielle Williams, a fourth-generation Army veteran who leads the "Diversify Outdoors" coalition, said people often ask her how she became interested in the outdoors, assuming she didn't grow up spending time outside and devaluing her relationship with outdoor spaces as a child.

"We have to kind of tone down the elitism and just think about our language when we talk about the outdoors, because car camping -- that's great. And camping in your backyard, if you live in a family home, that's also wonderful," she said.

Advocates like Williams and Tariq say they hope the moment since George Floyd's death in police custody brings attention to systemic racism in the outdoors as well as other parts of society and translates into a long-term change in attitudes and behavior.

"We are urging people who are maybe having this conversation for the first time to do the work. It's not just about a moment. It's about committing yourself to completely change your lifestyle," Williams said.

The National Park Service has tried improving diversity in parks by marketing to non-white communities, training staff on racial sensitivity, and working to hire rangers from more diverse backgrounds. But despite the effort less than 20% of the 20,000 employees are non-white, the agency said.

And after years of effort the number of Black, Hispanic, Asian and Native American visitors to national parks has only seen minor improvements, according to the report shared with ABC News.

Who is under-represented and why?

In national parks, the most prominent and famous natural spaces in the country, Black Americans are consistently the most underrepresented. In 2018, only 6% of visitors identified as Black, according to the new report, a slight decline from the previous year.

"We need to communicate that national parks, one, are part of your birthright," Vela told ABC News Live in an exclusive interview.

"Two, they're places of reflection and comfort -- recharge your battery, to learn about your history, whether it's your Latino history as an example, African American history, LGBTQ history. We have those sites and places and stories in national parks."

Lack of transportation to national parks and the cost of visiting were cited as the top reasons people -- especially Black and Hispanic Americans -- don't visit them more often, according to the study. Twice as many black and Hispanic Americans said they don't know what to do in national parks than whites. When asked if they share the same interests as people who visit national parks, 34% of Black respondents and 27% of Hispanics said no, compared with only 11% of whites.

Vela said the lack of transportation is an issue but they also want to raise awareness of parks closer to urban areas and online national park experiences.

A broader challenge

Advocates for diversifying the outdoors say stereotypes around who enjoys camping and hiking create a big barrier: what they wear, what gear they have and even when they do it. Combined with attitudes that people do outdoor activities to relieve stress has made it difficult to have tough conversations about race.

"When I'm walking to work with park rangers or with other campers and hikers who treat me in some sort of way that make me feel unwelcome, that make me feel unsafe, that is startling," Tariq said. "And that goes unchecked because there's, there's just no channel for us to be able to challenge that in such remote places."

Many advocates say public information about parks and outdoor activities are not tailored to communities of color. Posted signs, for example, are mostly in English rather than Spanish. Park ranger uniforms that resemble what is worn by law enforcement are intimidating to some immigrants and minorities in light of documented cases of profiling.

Williams said she adjusts her behavior in parks and public spaces, smiling or moving aside on a trail to let white visitors pass even though she's disabled and walks with a crutch. She called it an ingrained behavior to avoid any negative connotation with being a Black person in a predominantly white space.

"You're worried about somebody calling the police on you. You're worried about just having a negative interaction based solely on the color of your skin," she said.

National parks and the conservation movement were created as a way for people to escape cities during the industrial revolution, which Pannell said is one example of systemic racism in the outdoors that hasn't been confronted.

"In many ways, they are created by removing indigenous people from those lands and creating refuges for more affluent white people to get away from the city, which were becoming black and brown. So we have to -- we have to deal with that history and that legacy," he told ABC News.

Carolyn Finney, a storyteller and cultural geographer whose book "Black Faces, White Spaces" focuses on African Americans' relationship to the outdoors said the dominant narrative around national parks doesn't include that they were considered primarily with white visitors in mind.

She said that despite the value of the ideas that conceptualized the National Park Service and laid the groundwork for the modern environmental movement in the early 1900s, figures like John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt did not consider how those spaces would include people of color because they were actively segregated at the time. And some figures close to the conservation movement like Madison Grant, who founded organizations like the Bronx Zoo, espoused actively racist ideologies.

"You're looking at time during Jim Crow segregation, it didn't stop because we were talking about a conservation trail, or because we're talking about the environment. It did not stop," she said in a phone interview.

"And so for me, you know, we jumped ahead to a Christian Cooper experience or my own personal experience, or anybody of color's personal experience out in nature, walking that trail in the park. You know, they're not anomalies. Now it's all part of a -- is a long experience of things that have never been thoroughly addressed here and that it is really hard when something becomes normalized."

Many people of color say that history of the parks is another psychological barrier white Americans don't have to face.

"Historically, in the South, in particular, many atrocious things that happened to Black people were in the woods," said Frank Peterman, an outdoors enthusiast who began visiting the national parks with his wife Audrey 25 years ago.

Vela said he recognizes that history and fear it instills and is developing strategies to combat it.

"We have to be responsive to those needs and -- and deal with those needs because they're going to be different. And it's going to require a different approach. And so, we have to own that," he told ABC News.

Part of the solution, Vela and advocates agree, is to openly confront the racism associated with the parks and highlight the important stories of black, Hispanic, Native American and LGBTQ people in American history.

"I think that as a person of color, I think that our national parks and what I've found, is opportunities to really reflect on the most difficult and challenging times in our nation's history," Vela said.

And even on the current debate around the future of Confederate monuments in national parks, Vela said he won't remove any statue or memorial from national park land, saying it risks removing the story of why they were put there in the first place.

"If we do that on park land we then remove the stories that they contain. And if those stories are further sanitized in the history text, we can -- we may completely lose that narrative. We can't," he said.

Vela said he wants the National Park Service to provide information and facilitate conversations about that history so visitors are inspired to learn more and can decide what it means for themselves.

"Hopefully you're going to want to learn more. And do further research. And if that's the case, we did our job. But we're not going to make that decision for you," he added.

The future of national parks

Americans of all races in the new Park Service study said they value the nation's iconic parks and landmarks as important to America's national identity and think they should be protected. And advocates say they hope the current moment leads to future change and more attention to combating systemic racism in national parks and the outdoors industry and culture.

"(The parks) tell the story of the evolution of America. So if you want to know that story -- and now there's so much confusion about the 'real' American story -- you will find them in the national parks," said Audrey Peterman, who has visited 185 parks in 47 states with her husband.

"There's been a tremendous improvement and it's largely coming from inside our communities," she said.

And that future is a part of why Vela said further integrating national parks is a priority.

"If we don't make ourselves relevant to current and future generations, who is going to be the advocates for the protection and preservation of our nation's public lands at every level, whether it's at the local level, the state level and the federal level? And, who's going to wear these uniforms?" Vela told ABC News.

"We've got a lot of work to do. And you know we keep talking internally, about we're in a second century of service. We can learn from that first century our values aren't going to change. But how we do business has to," he said.