Americans suffer deadly fentanyl overdoses in record numbers

In the first 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, a record number of Americans died from drug overdoses. Although months of data is still incomplete, statistics show that most of the deaths involve the potent drug fentanyl.

According to the National Institute of Drug Abuse, fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. In the new series “Poisoned,” which explores the devastation caused by fentanyl, ABC News Live examines how many parents are learning the deadly reality of the drug only after their children have suffered a fatal overdose.

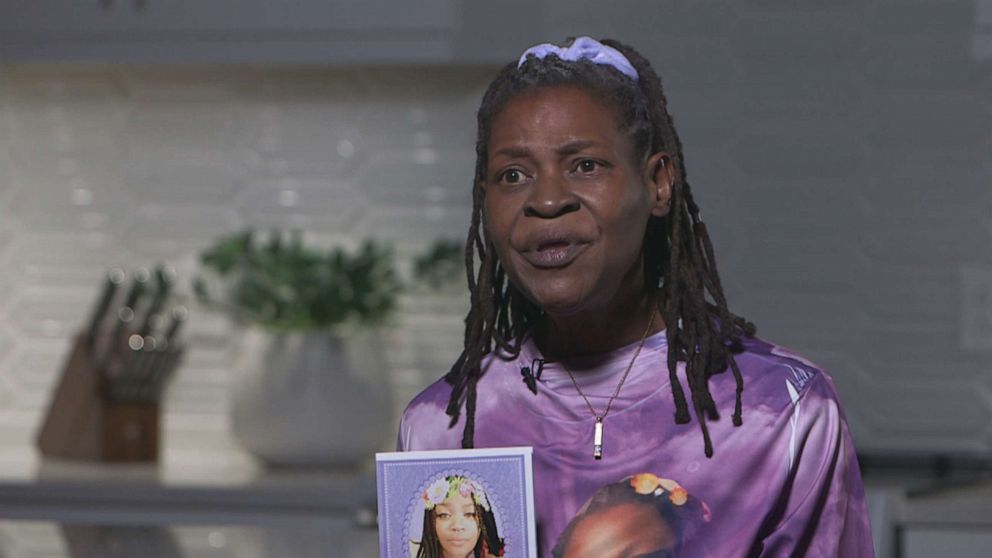

Romello Marchman grew up in Nashville, Tennessee. His mother said that he was a typical 22-year-old man who loved video games and cars.

“He was a young man like so many others out there,” said Tanja Jacobs. “They are stressed, they are worried. The pandemic keeps them away from their friends. They can't go to school.”

During the pandemic, Romello Marchman died from cocaine laced with fentanyl, according to Jacobs.

“He got it from his friends. And it's the only reason why he took it, is because he did get it from his friends and he did trust them,” said Jacobs.

Last year, Tennessee had the third highest overdose death rate in the country, according to the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

“In the Nashville area, between 75% and 80% of our fatal overdoses will involve fentanyl at this point in time,” said Trevor Henderson, the former director of the Nashville Overdose Response and Reduction Program.

That statistic accounts for the death of Frankita Davis.

Betty Davis said her daughter was diagnosed with cancer when she was 17 years old and that doctors had prescribed her pain medication. One day, a friend offered her daughter a pain-reliever pill that they did not know was laced with fentanyl, the mother said.

“She chose to take a pill, but she didn't choose to die,” said Davis.

Fentanyl, which was originally made for sedation during surgery, is one of the most powerful opioids ever created. Fentanyl-related fatalities began to skyrocket nationwide after drug dealers and cartels began to lace the chemical into drugs that they were already selling, often targeting addicted users looking for a more powerful high, according to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration.

“A few grains of fentanyl will make you high. A couple more will kill you,” said Sam Quinones, who authored a book on the U.S. opioid crisis. “It's just so potent and so profitable… Dealers are seeing that this is something they could sell in all manner of ways and to all manner of customers.”

Candice Sexton, a Nashville coroner, keeps a growing list of people dying with fentanyl in their systems. In 2016, her office noted 102 deaths related to fentanyl in middle Tennessee alone.

Every year since, those numbers have nearly doubled, Sexton said.

“It was just mind boggling,” she added.

In 2021, Sexton’s office reported nearly 1,200 fentanyl-related deaths. She said she expects 2022 to be even higher.

“We are on track for it to be worse,” said Sexton. “We have outgrown our cooler. We have a FEMA trailer that they're allowing us to use as well for additional storage.”

Phil Bogard is a program administrator at Rock to Recovery, a recovery clinic in Nashville for women suffering from addiction.

”In 2018, I remember people coming in for heroin,” said Bogard. “Now nobody's coming in saying, ‘I'm here for heroin.’ People are walking in the door saying ‘I'm here for fentanyl.’”

Naloxone, otherwise known as Narcan, reverses an opioid overdose. First responders said they are often administering multiple doses of Narcan just to resuscitate one person.

In Nashville, Henderson leads a small team of five people monitoring the fentanyl epidemic. One of their main goals is to distribute Narcan in parts of the city that have high numbers of overdoses.

“We can identify hotspots of activity. So we can look at ZIP codes that are hit particularly hard,” said Henderson.

Unfortunately, the growing number of fentanyl-related deaths is not unique to Nashville, but a scene playing out across the country. Like many other parents, Jacobs has been trying to spread the word about the dangers of fentanyl.

She said she is against the use of the word “overdose” and prefers to use the word “poison.”

“If you take too much of something, you overdose. You might or might not die,” she said. “But once that fentanyl is in there, if you get something you haven’t asked for and then you die from it - it's poisoning, which makes it a murder.”