America has a gun violence problem. What do we do about it?

This report is a part of "Rethinking Gun Violence," an ABC News series examining the level of gun violence in the U.S. -- and what can be done about it

Mass shootings have dominated the headlines, conversations and political debate around America's gun violence problem for decades.

Perpetrated in many cases with military-style rifles, they have become a symbol for some of America's obsession with guns, and high-powered ones at that, as well as a propensity for violence by some. Active shooter incidents have been on the rise in the two decades since a dozen students and a teacher were killed at Columbine High School in 1999.

Mass shootings and active shooter incidents have also continued to foster a deeply emotional and long-standing debate over both the number of guns and controls over those weapons in the U.S, all to end up with congressional gridlock and familiar arguments about mental health, millions of responsible gun owners and the Second Amendment.

It's a state of affairs that has become all too familiar -- and distressing -- to many across the nation and generations. It also makes the U.S. an anomaly in the developed world -- a wealthy country with an endemic gun violence issue and the seeming inability to solve it.

So, ABC News decided to dig deeper -- attempting to define the problem, explain key concepts and explore solutions in the multimedia series "Rethinking Gun Violence." We also developed a Gun Violence Tracker to help illustrate the daily toll of gun violence in America in partnership with the independent, nonprofit Gun Violence Archive because of the lack of up-to-date federal data.

Watch ABC News Live on Mondays at 3 p.m. to hear more about gun violence from experts during roundtable discussions. And check back tomorrow, when we look at what type of gun is used in most shootings in the U.S.

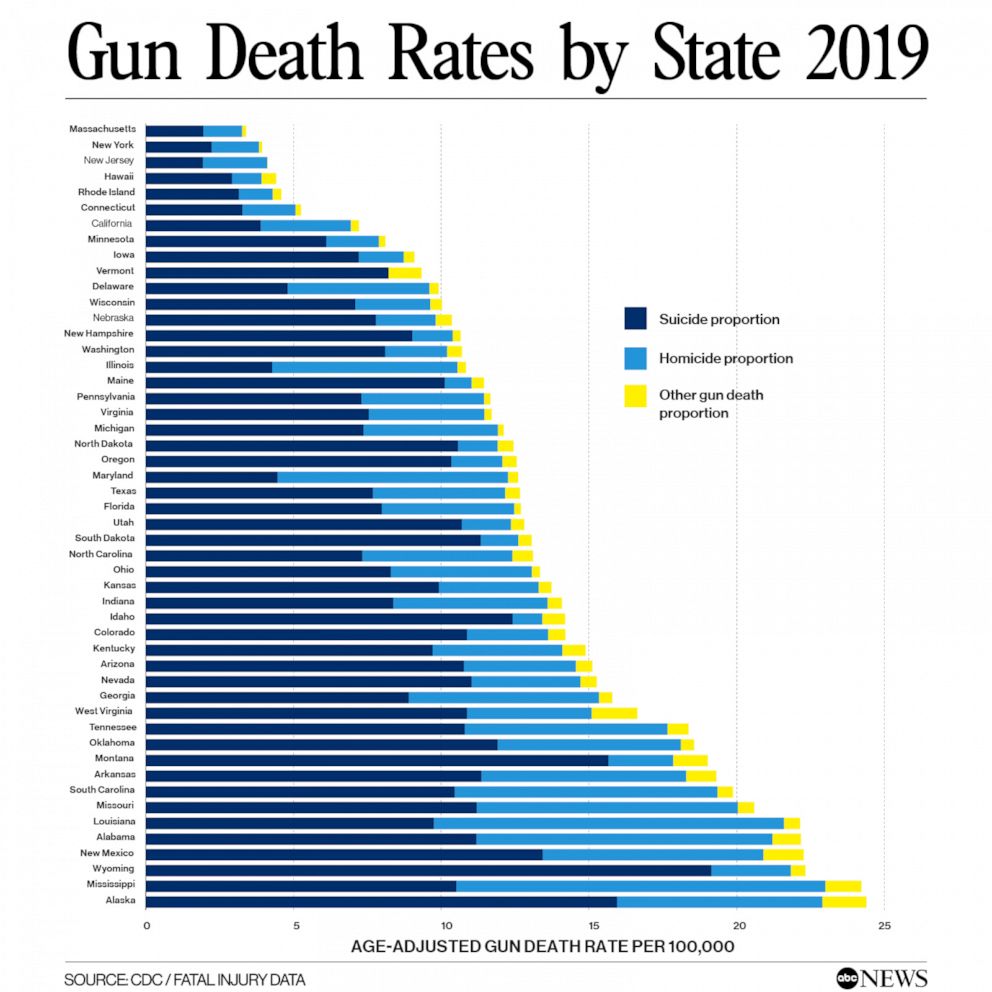

Touches all corners of the country, but not equally

Gun violence in America is a story that touches every corner of the country but does not affect everyone equally. It comes into shocking focus with mass shootings but also hides behind closed doors with little attention and costs the health care system more than an estimated $1 billion a year for injuries alone, according to a report released in June by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

It is seen as the scourge of urban living in some cases but also penetrates deeply into suburban and rural America. And many times, the victims are the gun owners themselves or their loved ones, either through suicide or accidental shootings. There are also the 2,606 gun deaths by law enforcement between 2015 and 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

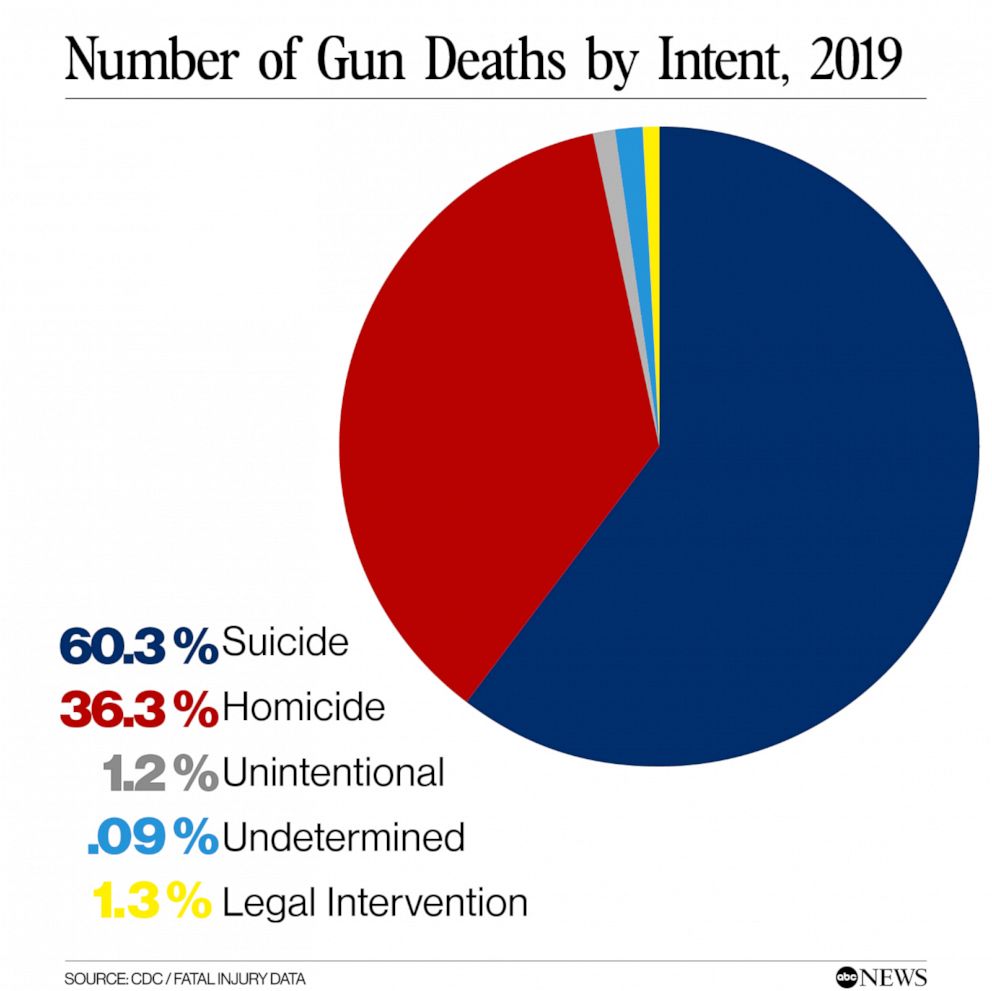

While homicides account for much of the carnage and terror associated with gun violence, the most recent data from health officials shows that suicides account for the bulk -- over 60% -- of gun deaths in America. And gun injuries, while they rarely make the news, put a tremendous burden on both American families and the health care system, according to health researchers.

What you don't hear about and what people don't assess is for every story of a mass shooting, there are, on average, 300 (other) stories, most of them suicide, that are never told.

If we are serious about tackling the gun violence problem in America, experts say we must look at the complete picture, which they say goes well beyond the headlines and amounts to not one, but several gun violence epidemics begging for solutions.

Dr. Georges Benjamin, the executive director of the American Public Health Association, told ABC News that gun violence goes beyond killings, and frankly, even crime. It has seeped into every aspect of American culture, from active shooter drills in schools and offices to the numbing feeling many people have that they could be shot at any moment, he said.

"We talk about gun violence but you have to think of guns as an epidemic of injury by firearms. That's the more practical way to think about this," he said.

Mass shootings get mass attention despite being an 'anomaly'

The FBI defines an active shooter, a very specific and relatively rare type of shooting incident, as "an individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a populated area."

Active shooter incidents, according to FBI data, have gone from three incidents in 2000 to 40 incidents in 19 states in 2020. During that period, shootings have erupted in schools, businesses and open spaces, to name just a few.

Twenty-six children and educators were killed in 2012 at a school in Sandy Hook, Connecticut. Forty-nine people were killed and 53 others were injured four years later at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando.

As of August 2021, the highest number of casualties resulted from an incident in Las Vegas on Oct. 1, 2017, when a gunman killed 60 people and wounded hundreds of others.

And while the perceived randomness and pervasiveness of these kinds of incidents has led to school lockdowns and an overall sense of dread regardless of age or locale -- they occurred in 43 states and the District of Columbia from 2000-2019, the FBI said -- there is a disproportionate focus on active shooter incidents in addressing overall gun violence in the United States, according to Benjamin.

Active shooter situations represent just one kind of mass shooting. But even that wider category resulted in a mere 1% of all of the 191,897 gun deaths between 2015 and 2019, according to the Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit which identifies mass shootings as cases in which four or more people are shot, and tracks them through public data, news reports and other sources. Mass shootings accounted for 2.8% of all of the 74,565 gun homicides during that five-year period, the GVA data showed.

"It's a rare anomaly," Kris Brown, president of the nonprofit advocacy group Brady: United Against Gun Violence, told ABC News of mass shootings.

"What you don't hear about and what people don't assess is for every story of a mass shooting, there are, on average, 300 [other] stories, most of them suicide, that are never told," Brown said.

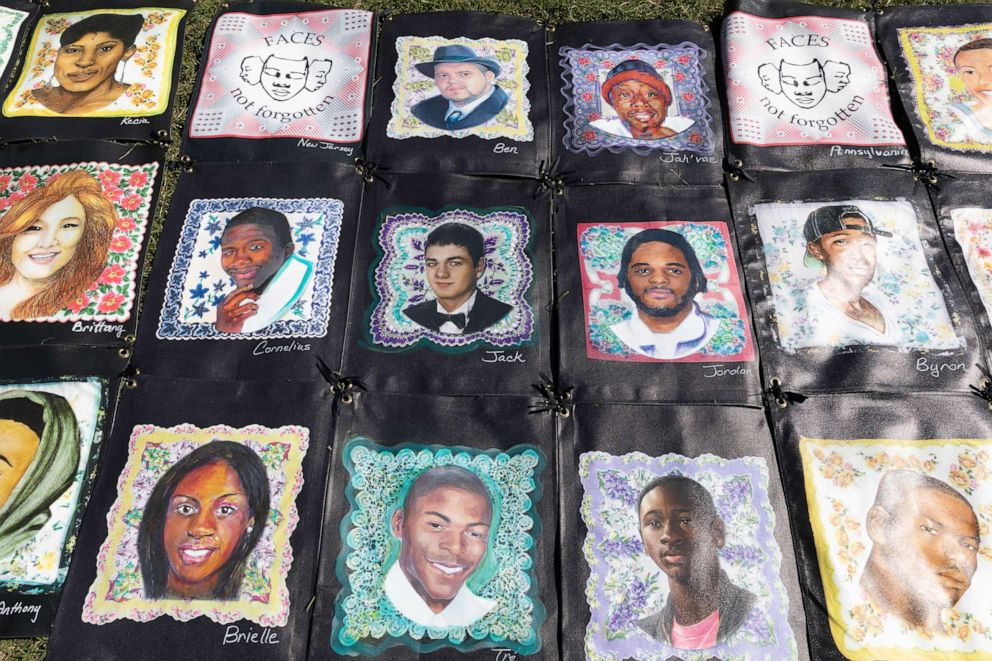

The impact of homicides goes beyond urban communities

About 74% of the nearly 95,000 homicides that took place between 2015 and 2019 were committed using guns, according to the CDC. Homicides, which had been on a downward trend for decades in America, have been increasing significantly since 2014, according to the agency.

The majority of gun homicides victims are young, Black men whose neighborhoods and communities are disproportionately impacted by gun violence as well.

Black Americans accounted for roughly 57% of all gun homicide victims in the country between 2015-2019, the CDC data showed. A majority of the gun homicide victims among Black Americans are those under 35, according to the CDC.

"Black males are disproportionately impacted and have by far the highest rate of gun death, nearly twice as high (1.8x) as the second-highest (and also disproportional) rate of gun death among American Indian/Alaska Native males," according to a CDC analysis of gun violence between 2015-2019. "Black males were more than twice as likely to die by firearms than white males in 2019."

Daniel Webster, the director of Johns Hopkins University's Center for Gun Violence Prevention and Policy, told ABC News that while gun homicides disproportionately affect Black people, it does not negate the fact that over 16,000 white people were killed in gun homicides between 2015 and 2019, according to CDC data. There were 1,071 Asian Americans and 11,213 Latinos killed by guns during this period, the CDC said.

"We go to these common perceptions that overstate things," he said.

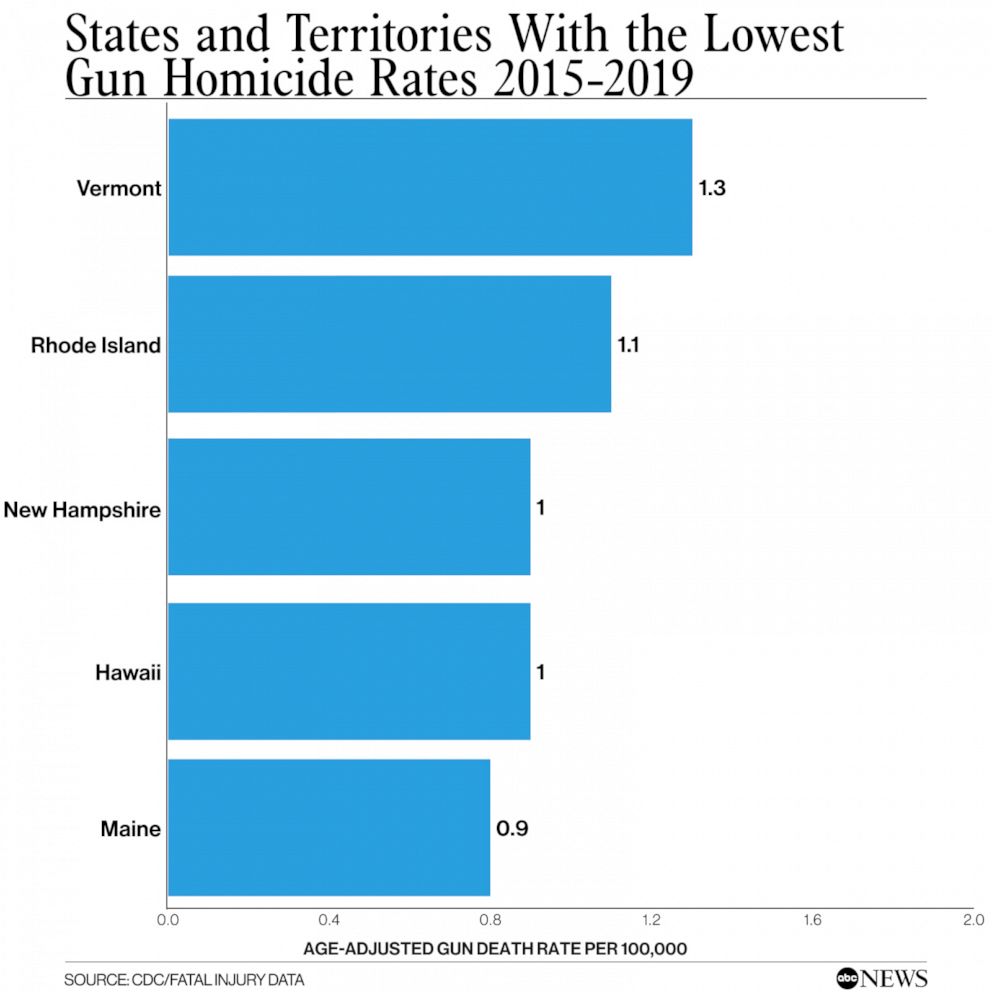

And while more than 50% of all gun homicides between 2015 and 2019 took place in the most populated cities in the country, according to the CDC, about half of them did not. Also, individual cities are not equally impacted by gun violence.

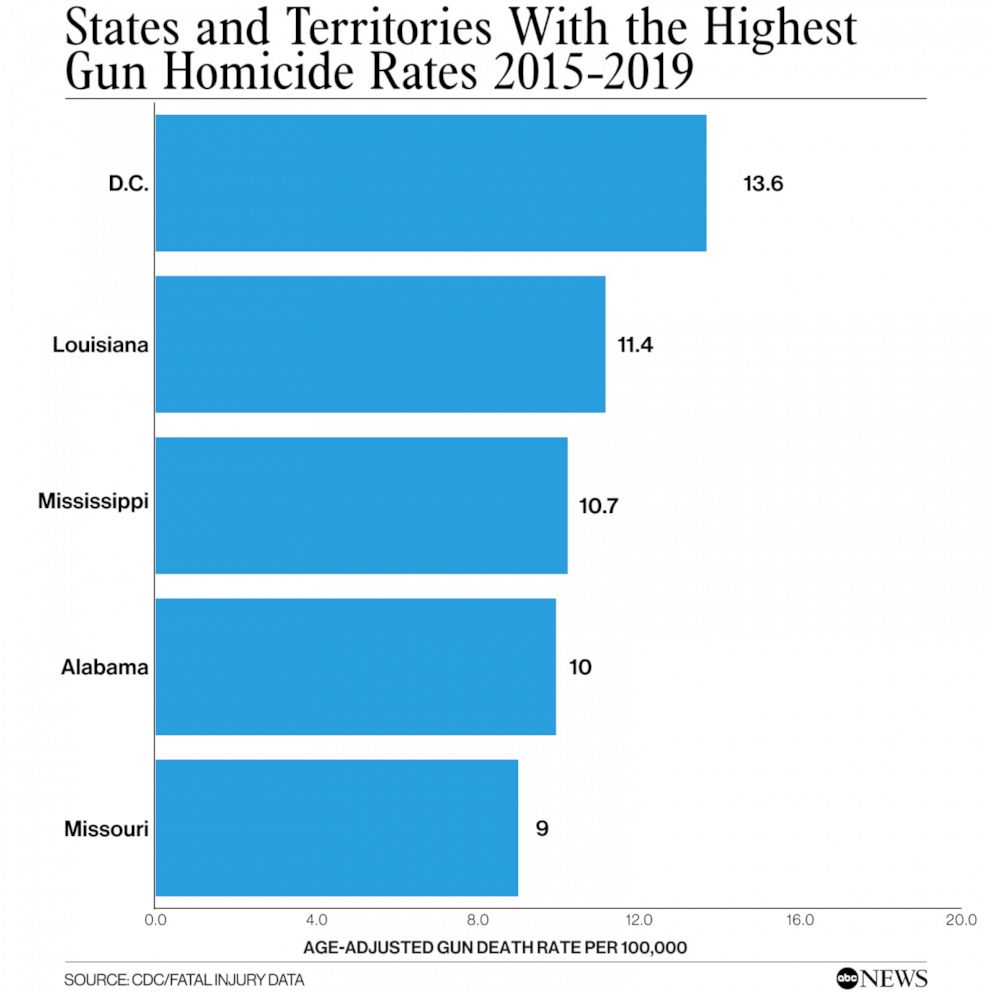

The national age-adjusted gun homicide rate was 4.47 per 100,000 between 2015 and 2019, the CDC data showed.

Some highly populated counties, such as Cook County, Illinois, which includes Chicago, had a high gun homicide rate of 12 per 100,000, but other urban areas, such as Brooklyn and Queens in New York City, had rates under four per 100,000, according to the CDC.

At the same time, the data showed high gun homicide rates in less populated areas throughout the country. Several states in the South had among the highest gun homicide rates in the country, with Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi recording rates above 10 per 100,000, according to the CDC.

Too many people think gun violence is an urban problem among Black communities. They don't realize that it's happening more and more in smaller communities in their neighbor's homes.

The gun homicide numbers are more striking in certain counties that have a fraction of the population of major cities.

For example, Mississippi County, Arkansas, which has a population of more than 42,000, according to U.S. Census data, had a gun homicide rate of over 23 per 100,000, the CDC showed.

Benjamin said there is no leading factor behind the gun-related killings, some are premeditated acts of aggression, some are domestic disputes, others are part of other crimes such as robberies, but the one common denominator is access to a firearm.

"I think the public does not understand the full scope, one, but they also think it's an urban problem," he said.

Injuries have an impact

Homicides only tell part of the story of the impact of gun violence on communities in the U.S.

In addition to homicides, 383,500 people were injured by guns between 2015 and 2019 -- roughly 76,700 people a year, according to the CDC.

Brown told ABC News that every year on average 33,242 people are unintentionally shot. Over 98% of these unintentional shooting incidents resulted in injuries and not deaths, according to the CDC data.

These include incidents where a gun goes off when someone thought it was unloaded, or a child was playing with a gun, according to Brown.

"A big proportion of [those incidents] is people with guns in their homes," she said.

A report released in June by the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that firearm-related injuries resulted in over $1 billion in initial hospital costs annually. The report said those costs are higher when factoring in longer-term costs such as follow-up visits and physical rehabilitation.

Webster said there is also another factor that's been difficult to quantify: the mental impact just from being threatened by a firearm.

Even if no shots are fired, the mere sight of a handgun in front of a victim's face is enough to do serious damage to mental health, he said.

He added that intimidation is a major factor in domestic violence cases, particularly if the abusive partner is armed.

The Education Fund to Stop Gun Violence calculates that almost half of all women murdered in the U.S. are killed by an intimate partner, former or current, and more than half of these killings are with a firearm.

"Women are five times more likely to be murdered by an abusive partner when the abuser has access to a gun," according to the organization, which notes that "even when a weapon is not discharged, abusers often use the mere presence of a gun to coerce, threaten, and terrorize their victims, inflicting enormous psychological damage."

Suicide: The biggest driver of gun deaths

Researchers and advocates say not enough attention is paid to gun suicides, which account for over 60% of all gun deaths annually -- 117,000 Americans between 2015 and 2019, according to the CDC.

Half of all suicide deaths in the U.S. are from guns, the data showed. And while only 10% of attempted suicides involve guns, the high percentage of fatalities from gun suicides reflects the fact that roughly 87% of all gun suicide attempts are successful, according to a Brady: United Against Gun Violence analysis of CDC data from those years.

Another 17,770 people were injured by a gun suicide attempt during that period, according to the CDC.

While Black men are disproportionately impacted by gun homicides, over 100,000 white Americans died by suicide with a gun between 2015 and 2019, according to the CDC -- representing 85% of all gun suicides during the five-year period.

In fact, the rate of gun suicides among white Americans was more than 2 1/2 times greater than Black Americans, CDC data showed. The majority of gun suicide victims are white men between the ages of 45 and 65.

"We talk about the mass shootings or the kid in the city that's shot, but we're not talking about the other forms of gun violence, the depressed, lonely man who took his own life with a gun," Benjamin said.

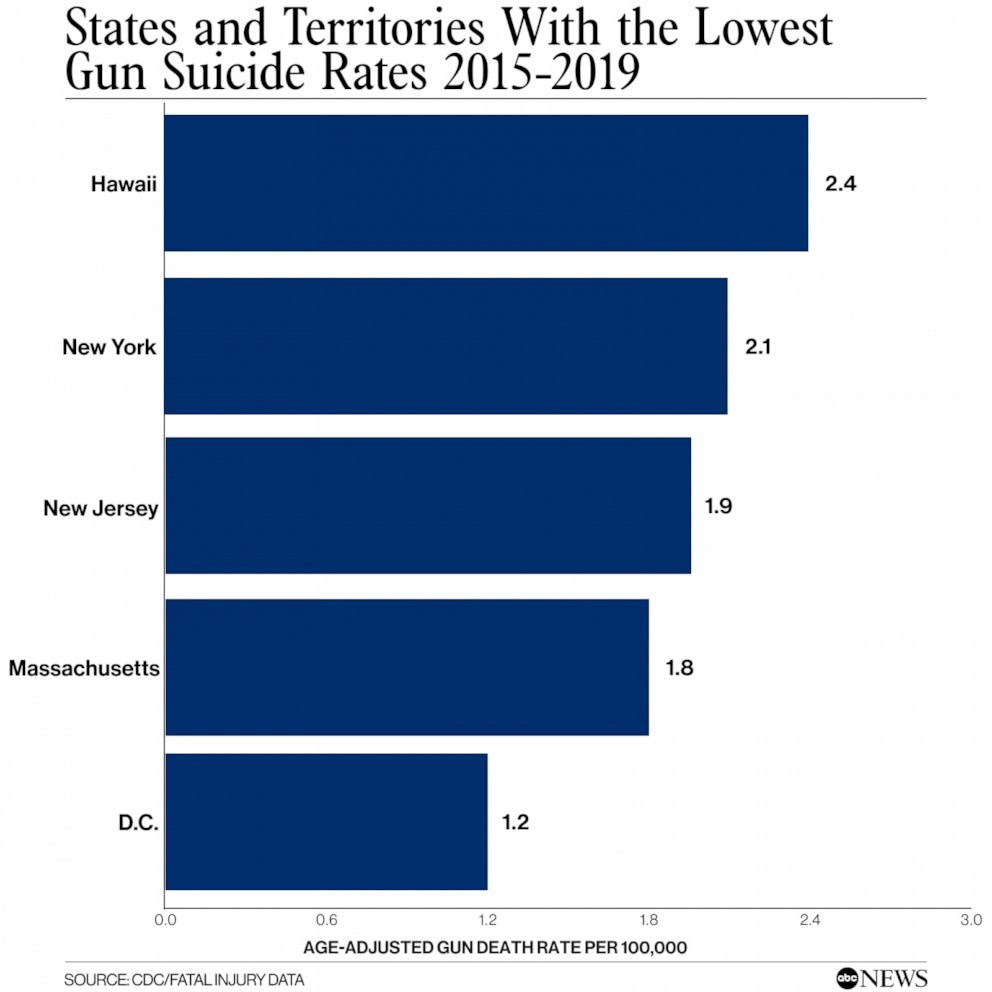

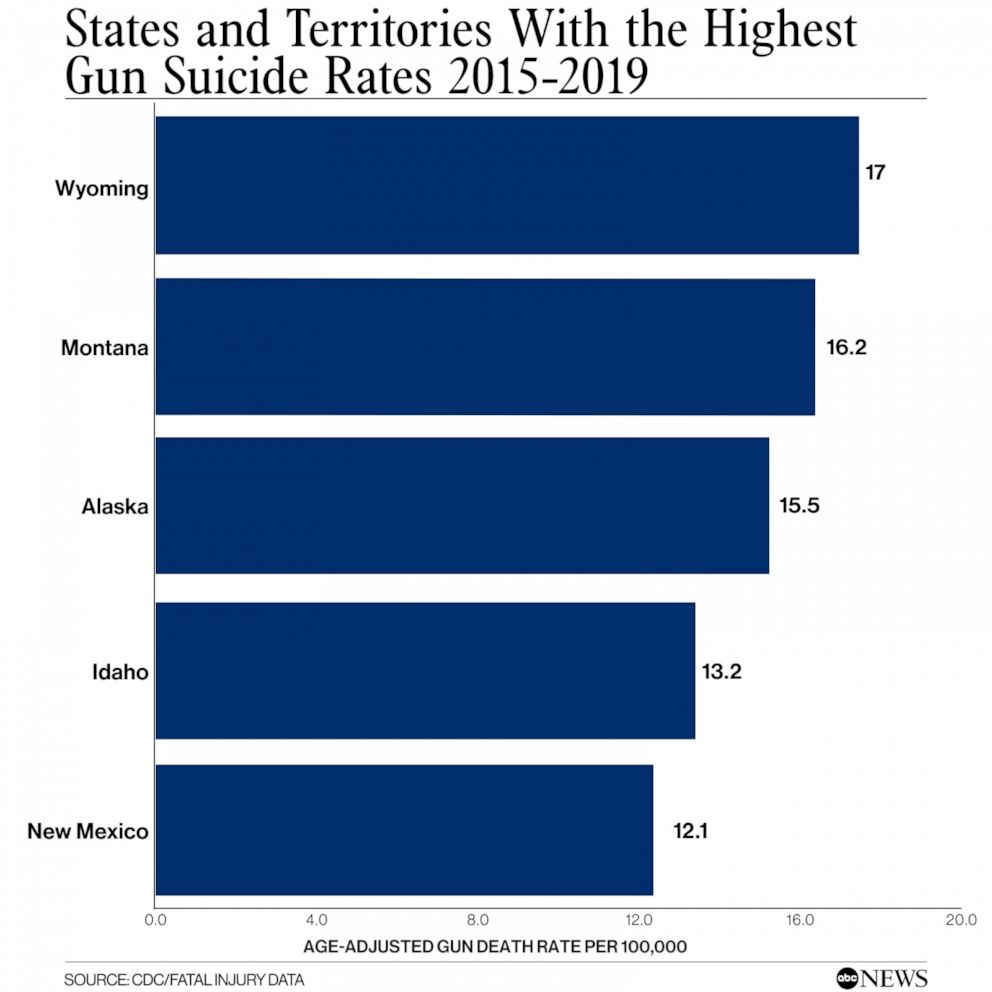

Geographic data from the CDC showed that the gun suicides between 2015 and 2019 took place throughout the country and that in 39 states, the per capita suicide rate was greater than the per capita homicide rate. In several states, such as Alabama, Kentucky and Tennessee, the suicide rate was higher in rural counties.

In a few locations, such as Okmulgee County, Oklahoma, both the gun suicide and gun homicide rate per 100,000 people was above 10.

Three states -- Arkansas, Alaska and Wyoming -- had rates of suicide higher than 15 per 100,000 people, according to CDC data.

A study by Everytown for Gun Safety, a nonprofit that advocates for gun control and gun safety, found the rate of firearm suicides was five times higher in rural communities than urban communities.

Webster and other researchers added that the lack of media coverage on gun suicides has resulted in a lack of understanding of who is most affected by gun deaths.

"Too many people think gun violence is an urban problem among Black communities," Benjamin said. "They don't realize that it's happening more and more in smaller communities in their neighbor's homes."

Overlapping but distinct problems

Although health researchers acknowledge there is no single solution to stopping gun violence, Webster said there is some overlap among the different forms of gun violence and acknowledging those common threads is the first step to curbing shootings.

For example, roughly 32% of all mass shooting suspects in the last decade died by suicide, according to Everytown for Gun Safety.

"There are a lot of misconceptions that a mass shooting is random. They are typically planned events against some grievance," Webster said. "In most reports, there were warning signs that were missed."

A study released in May in Injury Epidemiology found in 68.2% of mass shooting incidents between 2014 and 2019, the perpetrator either killed at least one partner or family member or had a history of domestic violence.

Access to a gun is more likely to lead a person to use it on more than just one person, Webster said.

"They develop behavior patterns that make them more prone to violence in all of its forms; violence against intimate partners, violence against the community and violence against themselves," he said.

Potential solutions

Experts who have been studying gun violence say people are more likely to find common ground when the focus is taken off mass shootings and it is instead approached as a multi-faceted problem.

Jenna Longenecker, 32, an activist who lost her mother in 2012 to a mass shooting at an Oregon mall and later her father to a gun suicide, told ABC News that the public and political leaders were more willing to consider a bill that mandated all firearms be secured with a trigger or cable lock in a secured locker after hearing from families who lost someone to gun suicide.

"When someone wants to take their own life it's less scary and harmful than a person running around killing a bunch of people," she said. "That all changes when you know someone who took their own life with a gun."

Paul Kemp, co-founder of the grassroots group Gun Owners for Responsible Gun Ownership, said statistics, testimony and anecdotes from families who lost their loved ones to gun suicides helped sway the Oregon legislature to pass the law this year. According to both Kemp and Longenecker, other gun deaths were mentioned and emphasized by the bill's supporters but it was really the suicides that tipped the scales.

"Because we have these consequences, we're having the conversations," he said.

Oregon State Sen. Ginny Burdick, who was one of the chief sponsors of the bill, told ABC News that residents have raised their voices about the growing number of suicides and demanded action. Although gun rights groups tried to fight the bill, there was little opposition in the public, even among many gun owners, she said.

For a growing number of residents, the rise in gun violence in all forms, especially suicide, got to the breaking point and they had to speak out.

"It's not a taboo in Oregon. We've been very straightforward about talking about suicide, because it's an epidemic," the senator said.

Kemp said the bill has wide-ranging effects on gun violence. Having a weapon in a locked locker and unloaded lowers the risk of a child getting their hands on it or the weapon being stolen, he argued.

"Most gun owners I know grew up knowing this, that you needed to keep your gun in a secure place away from children," he said.

This year, a similar secure storage bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate.

Brown predicted that similar legislative action in other states would be more likely if there was a better understanding of the multiple facets of the gun violence problem.

He and other advocates acknowledged that a safe storage law doesn't solve all of the issues surrounding gun violence, such as domestic incidents and gang-related violence, but say that it sheds light on how to build consensus and come up with solutions.

And while some solutions may work for one kind of gun violence and not for others, a comprehensive strategy to address gun violence requires a full picture of the problem, which it turns out looks quite different from the impression the casual observer may be getting, Brown and other activists said.

"Part of the thing we expect from politicians is not just voting on bills, like safe storage and expanded background checks, but also amplifying to their constituents where the violence comes from," Brown said. "That violence happens every day, and if they don't acknowledge it, it will get worse."

If you are struggling with thoughts of suicide or worried about a friend or loved one, help is available. Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 [TALK] for free, confidential emotional support 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

ABC News' Mark Nichols contributed to this report.