9/11 male breast cancer patient: 'We're the forgotten people'

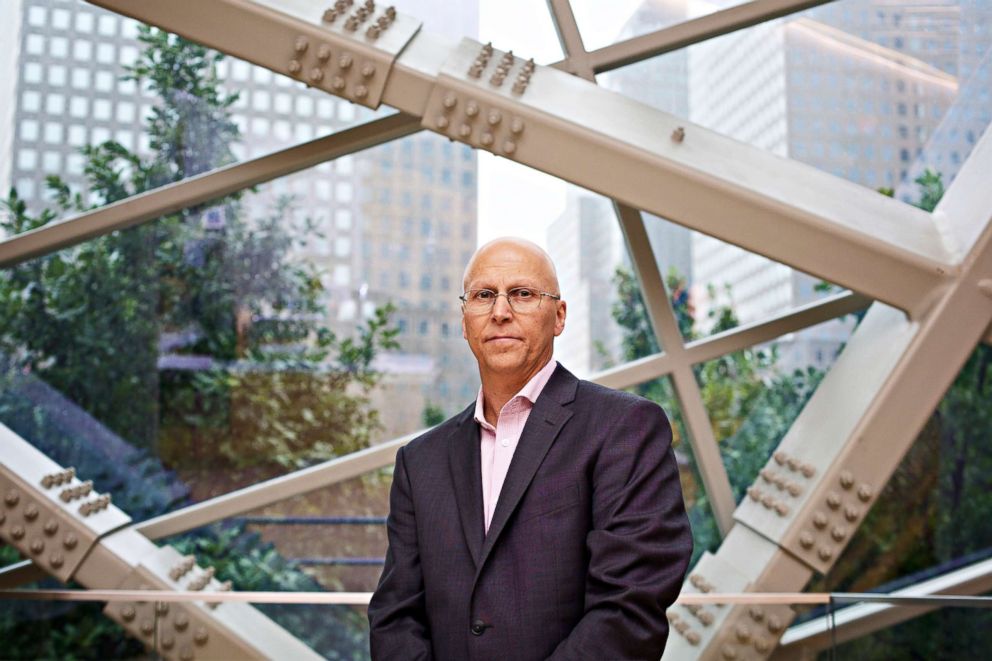

Jeff Flynn had no idea men could get breast cancer, so “I ignored the symptoms,” he said of a disease commonly associated with women.

But the “dreaded” diagnosis came in 2011, 10 years after the then-strategic account manager for EMC Corp., a data storage company, had worked recovering business accounts for his company in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, World Trade Center attacks.

“That required me to be on site,” Flynn, 65, told ABC News, adding that he toiled in lower Manhattan for six months.

“The pile burned for 99 days. For 99 days there was still soot, ash and that burning smell in the air. I certainly breathed toxic air and fumes, dust and smoke in the downtown area.”

Flynn is now among at least 20 men, all represented by the New York law firm of Barasch & McGarry, who say they are struggling with this relatively rare form of cancer as a result of their proximity to Ground Zero.

While there is no proven medical link between incidences of male breast cancer and 9/11 fallout, a surgeon told ABC News, there is “potentially a link to environmental factors.”

“Were there higher levels of radiation during that time period or was there something more pronounced in the air?” Dr. Roshni Rao, chief of the breast surgery program at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center in New York City, told ABC News. “I don’t think they’ve gotten to the bottom of that. From the data I have seen, it’s well within the realm of possibility but not definitely linked.”

Of the 20 male breast cancer victims represented by Barasch & McGarry, more than half have received financial awards from the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, according to the firm.

That federal program was established by the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act of 2010 to provide medical monitoring and treatment for WTC responders. To qualify, a patient has to certify a link between their cancer and 9/11 before an award is granted.

“Buildings [that] were insulated with asbestos were on fire for 99 days,” attorney Michael Barasch said. “The concrete dust alone had the same pH level [toxicity] as Drano, so it’s no surprise we’re seeing these incredibly rare cancers.”

Risk is smaller than mortality rates

Dr. Jennifer Ashton, ABC News' chief health and medical correspondent, emphasized that “we need to remember men have breasts too and, as such, they also get breast cancer. While it is much less common in men, it does occur and often carries a difficult stigma for men that they are battling a ‘woman’s disease.’

“It serves as a reminder for all of us to not gender-stereotype diseases or conditions in medicine.”

An estimated 400,000 first responders, residents, workers and others were exposed to the caustic dust and toxic pollutants in the dust and debris cloud from the collapse of the WTC buildings in 2001, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). They were responders and those who lived, worked and studied nearby.

All told, 15 to 23 men with breast cancer had been certified by the WTC Health Program as of July 31, 2018, according to the CDC.

Dr. Kristi Funk, who was Angelina Jolie’s breast cancer surgeon, said in general, “male breast cancer accounts for approximately 0.8 percent of all breast cancer cases; about 2,470 men annually.”

“In American men, the lifetime risk of breast cancer approaches 1.3 in 100,000. This means women are 120 times more likely to get this disease.”

But because men like Flynn don’t even recognize male breast cancer as a possibility, “their diagnoses usually come at later stages, increasing overall mortality rates,” she added.

Flynn, who first spoke to the New York Post, told ABC News he was 48 in 2001 when he agreed to work downtown because “we were told the air was safe by the environmental protection agency. [Then-Environmental Protection Administrator] Christine Todd Whitman had put out a public notification that the air downtown was safe to breathe and my company put a notification, email out that the air was safe to breathe.”

“[His employer] EMC didn’t have anyone monitoring the air; they took that from the government,” the East Meadow, Long Island, man said. “So, I trusted them.”

Some of his colleagues did not and refused to go downtown. “At least one employee told me, ‘I’ll go down if you buy me a mask.’ I did but he still refused to go downtown. In hindsight, he was smarter than I was. At the time I didn’t appreciate it,” he said softly.

Flynn was diagnosed with breast cancer in September of 2011. That was a year after his first symptom, which he noticed while lifting up his dog, who bumped into his chest and triggered pain.

He felt a bump, he said, but thought it was a gland or cyst. “I didn’t know that a male could get breast cancer. So, I ignored the symptoms,” he said, adding that the pain subsided and the lump flattened out a little.

A lump that doesn't hurt

Dr. Rao, the chief of breast surgery at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, said the first sign of breast cancer in men is, typically, “a lump that doesn’t hurt.”

A few months later, Flynn said, he and his wife took a beach trip to Florida, where she noticed that his left nipple was inverting. A sunken nipple that is getting flatter or inverting (retracting inward) is one of the breast cancer signs men should watch out for, according to Dr. Funk, Jolie’s surgeon.

Flynn underwent a needle biopsy and, three days later, received the “dreaded call” from his doctor that the cells tested positive for breast cancer.

He was diagnosed with Stage 3C breast cancer, which ultimately spread through his lymph nodes to reach Stage 4 metastatic breast cancer.

“It was devastating. The testing for this is brutal,” he recalled. “Right now, I’m cancer free but have to stay on drugs for the rest of my life.”

With his soaring medical bills, he was advised to apply to the Victim Compensation Fund (VCF). “I did not know how to apply and deal with all the questions and so, since the law firms are only allowed to take 10 percent of the fee, I contacted Michael Barasch” at the advice of a friend, he said of the lawyer. There is no lawsuit involved.

In February 2018, Flynn said, he got a “six-figure award” from the VCF. “Getting that award and the coverage for my medical bills is life-changing,” he said. “I swore if I survived this, I would help others by raising awareness and supporting other men.”

He did the right thing

Michael Guedes, 65, is another breast cancer victim and Barasch client.

He was an NYPD sergeant out of the 40th Precinct detective squad in the Bronx when the planes hit. He and fellow officers deployed downtown in school buses.

Close to a year after the attack, Guedes spent his time either at a nearby landfill where the debris was dumped or the temporary morgue at Ground Zero.

“The debris and everything that came from Ground Zero was taken to Staten Island landfill. We would take the debris and spread it,” he said. “If we recovered body parts or personal possessions, we would hand them in for identification.”

Guedes retired in January 2003 after 20 years of service and moved to Florida. In late-April 2015, his girlfriend, Maria Rodriguez, felt a lump on his right breast.

She had just checked herself and decided to examine him. Guedes followed his girlfriend’s advice and went to his primary-care physician, who referred him to a surgeon. His biopsy came back positive for breast cancer.

He had his breast removed and was put on chemo for six months, followed by radiation. He is now on the drug Tamoxifen, an estrogen receptor modulator, which he has to take daily for five to 10 years.

“Right now, I’m in remission. You’re not cancer free until you hit the five-year mark. I’m under 3.5 years,” he said. “I’m hoping for the best. I have no history of breast cancer in my family.”

Guedes did exactly what Dr. Rao recommends when they feel or see a lump. “Because the incidence of breast cancer is so low,” she said, “we are not routinely recommending that men get mammograms. But if they feel something it is important; they should be evaluated by their physician. Don’t ignore it.”

Guedes also took someone’s advice and signed up for the World Trade Center Health Program when he was still on the force.

The federal government set up the program to help people with health problems related to the attacks and to pay for the cost of their care.

Only 80,000 people have registered with the program for screening and care out of the 400,000 who were exposed.

Dr. Gaetane Michaud, who is the chief of interventional pulmonology at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, says some “people don’t know they are eligible and some people have left the state,” adding that “people were very young at the time and may not have had any risks manifest and are unaware of their potential risk.”

Guedes, with the help of attorney Barasch, also filed with the Victim Compensation Fund for medical coverage and was compensated in 2016.

As of August 31, the Victim compensation Fund had 20,874 claimants eligible for compensation. The VCF has made initial award determinations on 19,204 of those claims and has issued revised awards on 5,011 claims because of an amendment or appeal. The total amount awarded to date is more than $4.3 billion.

'We’re the forgotten people'

John Mormando was 34 when the towers came down. “I was home with my son because my wife was on a trip,” he recalled. “I was working at the New York Mercantile Exchange. I was home for a week in the aftermath but the next week they decided to open up the exchange. We came back with much fanfare. We were the first business to open in the Ground Zero area.

“We had Mayor [Rudy] Giuliani, Senator Hilary Clinton, Governor [George] Pataki and EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman.”

Mormando, like others, was told it was OK to go return. “They handed us little surgical masks like that was going to help anything,” he recalled. “They called us all heroes. We ate it up and went back to work.

The New Jersey resident did not exhibit any symptoms for years. He became an endurance athlete. He ran the Iron Man triathlon in September 2017 followed by the NYC Marathon in November.

But then he felt a painless bump in his chest in March of 2018. His went to his doctor and got a biopsy on March 19. Four days later, he learned he has an invasive ductal carcinoma, a form of breast cancer.

He had surgery at NYU Langone where his breast surgeon removed his right breast.

His surgeon also did a breast reduction on the left side just to balance things out visually. That’s when he was diagnosed with an undetected cancer tumor in his left breast.

“Not only is it rare for a man to get breast cancer, it is even more rare for a man to get bilateral breast cancer,” he said.

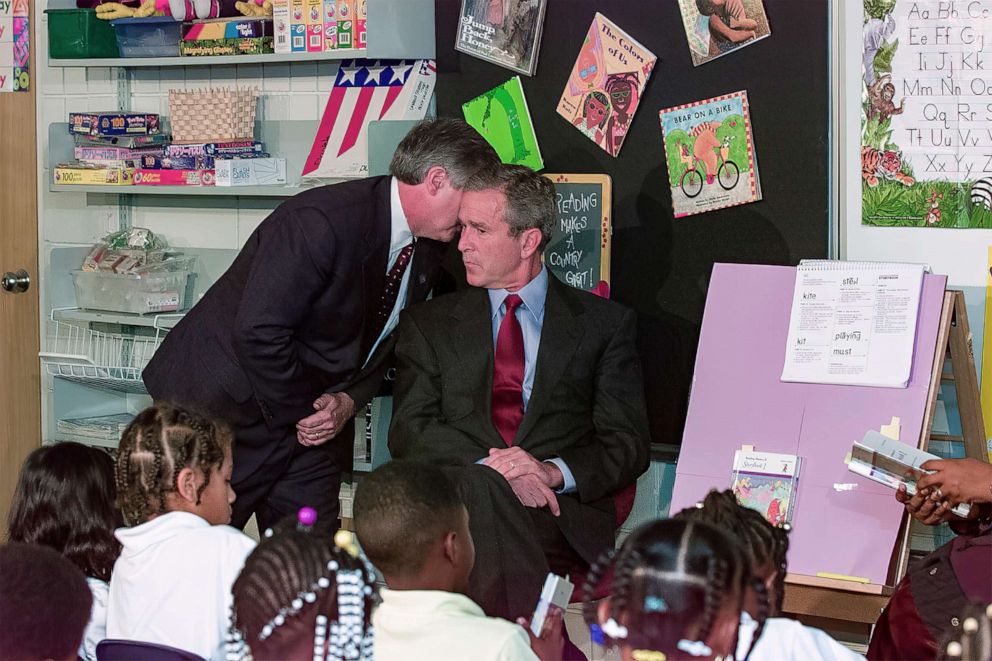

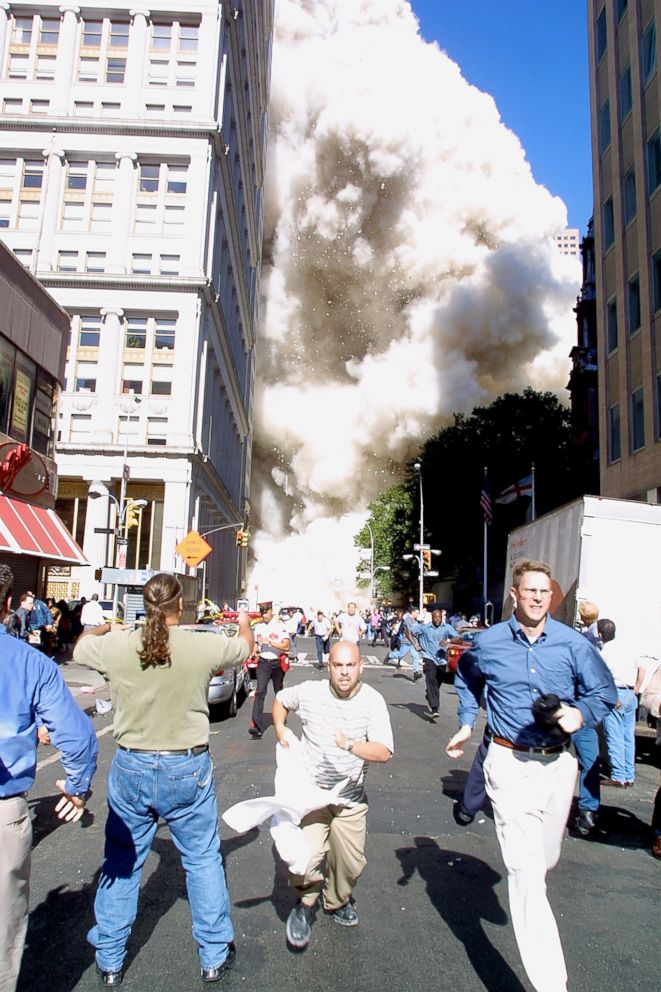

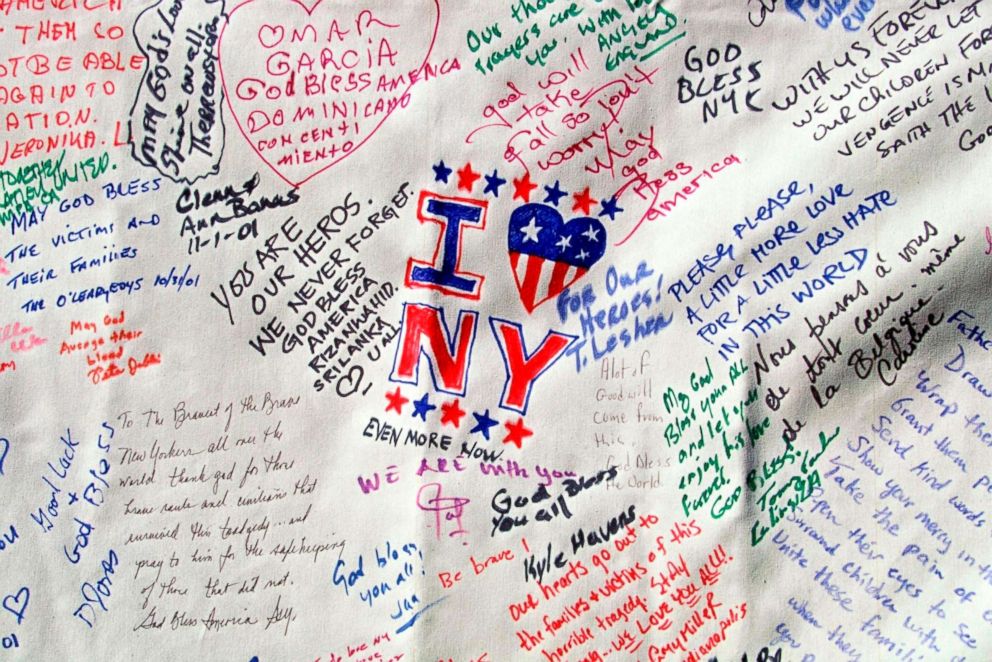

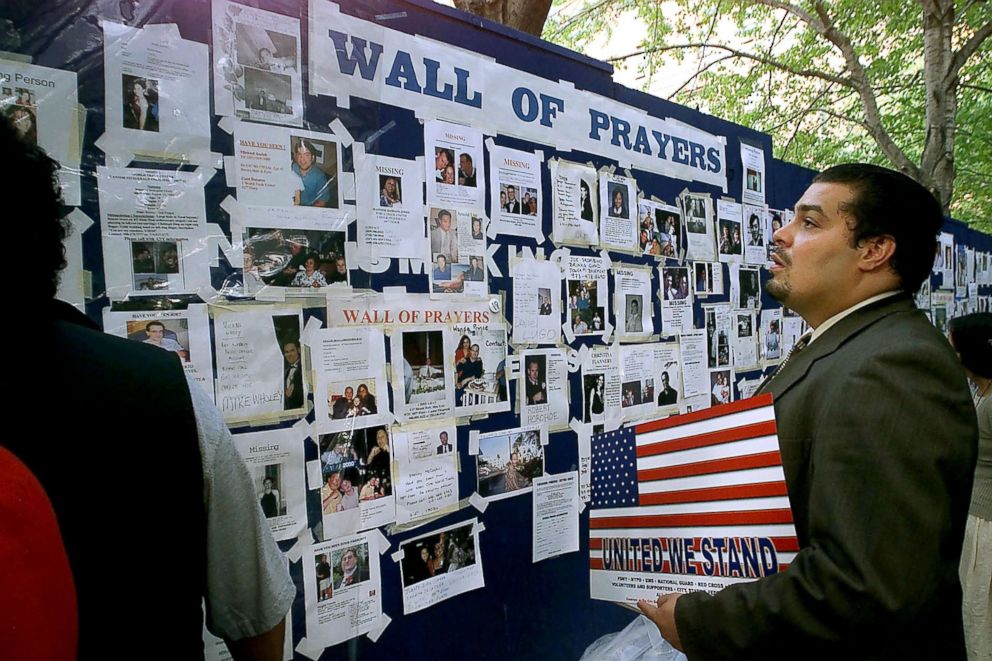

PHOTOS: Remembering 9/11

Some of the most iconic images from that fateful day in American history.They also found cancer in six of his lymph nodes, which resulted in his doing chemotherapy and radiation at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSK Bergen), which is close to his home in New Jersey.

When Mormando found out he had cancer, he confided in a friend who told him that he had an autoimmune disease that he contracted from 9/11 toxin exposure. His friend connected Mormando with lawyer Barasch.

“I was unaware that this exposure affected people other than the first responders,” he said. “We’re the forgotten people. There are people who worked down there. There are students who studied there. I have not been compensated as of yet.”

He added: “The compensation that they’re giving out is not life-changing money at all. When you look at what we’ve gone through, the compensation is really nothing,” he said.

“I’m speaking out because I want people to be aware that men can get breast cancer. If you feel a lump on your chest, don’t blow it off. Go get yourself checked out. The quicker you find out, the easier it is to save your life. If you worked or lived near Ground Zero, you are more at risk.”

If you believe you may be at risk from exposure after the Sept. 11 attacks, go to CDC.gov/WTC to apply for free screening.

ABC News' Aaron Katersky contributed to this report.