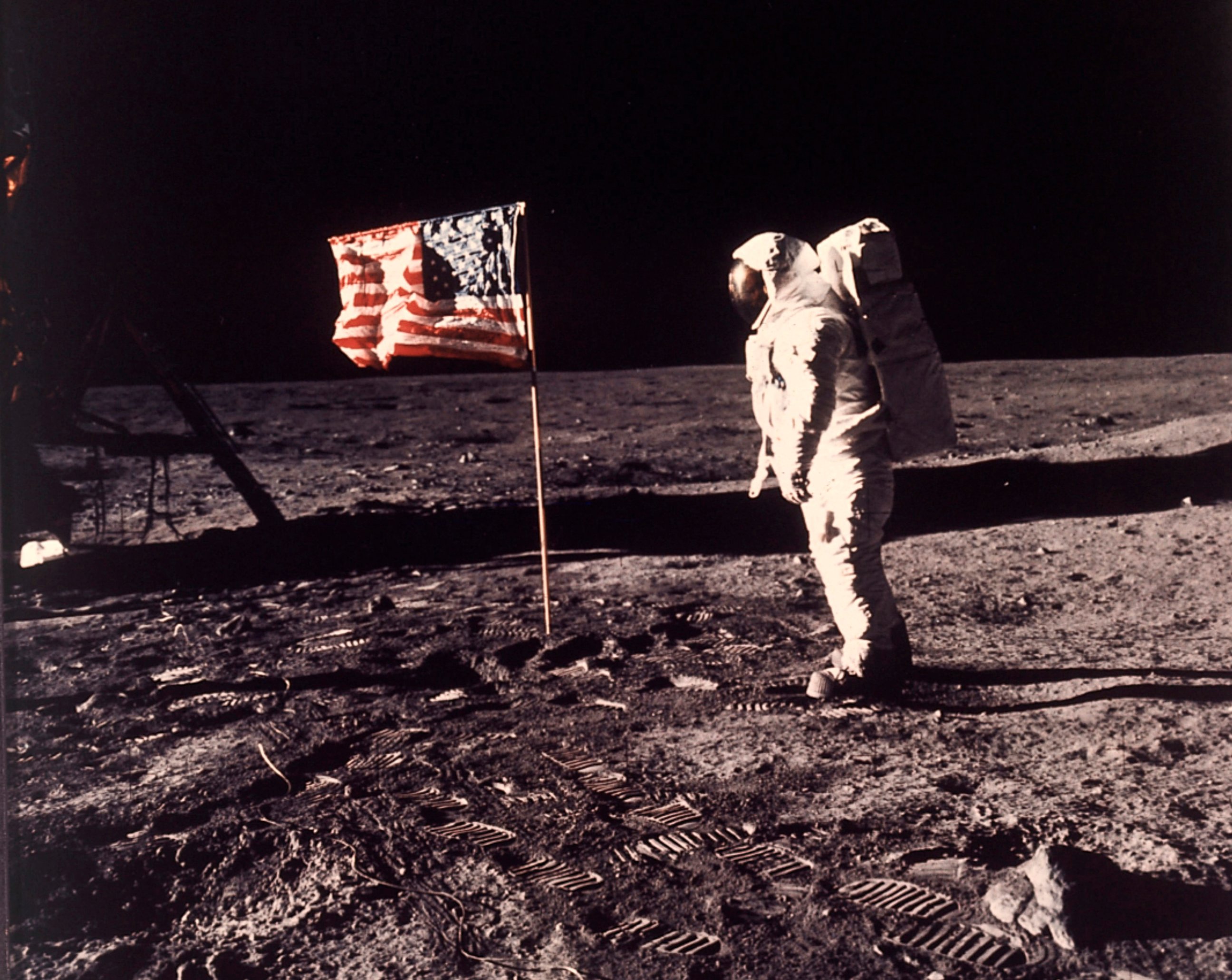

50 years after the moon landing: How close is space travel, really?

When Americans first walked on the moon 50 years ago, the idea of space travel crystallized into a graspable future. Bolstered by a geeky shift in pop culture that launched and relaunched franchises like "Star Wars," "Battlestar Galactica" and "Star Trek," Americans saw intergalactic storylines that never touched Earth. Life in space seemed so close.

Yet the last time Americans went to the moon was in 1972, and with the closure of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)'s space shuttle program in 2011, the U.S. government currently doesn't have the ability to fly astronauts anywhere.

"There's a couple young people who watched the lunar lander 50 years ago and thought: 'By 1980 we'll have bases on the moon and by 2000 we’ll be on Mars,'" Commercial Spaceflight Federation (CSF) President Eric Stallmertold ABC News. "And there's a bunch of entrepreneurs who are thinking, 'Why can’t we do that?'"

It's exactly that frustration -- that we've not further explored space -- that could lead to the closest we'll get to space tourism yet, possibly by the end of this year.

Richard Branson's Virgin Galactic and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin plan to take passengers to suborbital space -- where the Earth's atmosphere meets outer space -- which is 62 miles (100 kilometers) above sea level.

Impatient with the government, space exploration has shifted into the hands of private companies in the last five decades, founded by an elite trio of titans in other industries, the geek fantasy Billionaire Boys Club of Branson, Bezos and Elon Musk's SpaceX.

"There is a frustration among space barons and the space industry in general that there isn't a base on the moon, that we haven't been to Mars, we haven't done any of the great things after Apollo," Christian Davenport, author of "The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos," told ABC News.

The closest the average person (with means) is to becoming an astronaut would be to fly to the edge of space with Virgin Galactic, which expects to start these trips in as soon as a few months.

Branson's company completed two manned flights to the space this past year. The trip goes to what's considered suborbital space or the edge of space to experience about four minutes of weightlessness and look down at earth from the edge of its atmosphere.

Despite the $250,000 price tag for the flights, Virgin Galactic's wait list is real: the company said that 600 future astronauts have paid $80 million in deposits.

Bezos' Blue Origin is next on track to get flights into suborbital space. He plans on sending humans into space in 2019 on New Shepard — a suborbital vehicle designed for space tourism — which uses liquid hydrogen."

"We’re going to be flying humans in New Shepherd this year," Bezos said in May.

Bezos openly talks about his admiration for Gerard K. O'Neill, a space activist who was a big booster for space colonies.

"In the short term, what he's trying to do in his lifetime is to make space more affordable, more accessible, to fly much more frequently," Davenport said. "Richard wants to do the same thing at Virgin Galactic and Elon wants to do the same thing at SpaceX and that's the connective tissue that binds all of them together. They want more people going to space, they want more vehicles going to space with more regularity."

"In a good year you might fly rockets a couple times a month as opposed to multiple times a week and that's what they're aiming for," Davenport said. As space trips become more frequent and commonplace, "you get better, your operations become more efficient, your costs go down, and that's what they're ultimately trying to do."

Musk's goal in founding SpaceX was to go to Mars and "borne out of the frustration that NASA hadn't been there at the time Elon was founding SpaceX. He wanted to speed that up," Davenport said. SpaceX has been successfully launching reusable rockets for years, and taking cargo to the International Space Station.

Still the Apollo 11 anniversary has highlighted the lofty goals of all potential players pushing into space travel.

"This year, and going into next year, will be the most exciting time in the space industry since the Apollo era," Stallmer said. "They’re really close to getting the general public and private astronauts."

But that horizon may be further out than the industry wants.

Since 2011, American astronauts travel to the International Space Station (ISS) on Russian rockets, at a cost of about $87 million per seat, in effect funding the Russian space program, said CSF's Stallmer.

Boeing and SpaceX are currently in a race to start flying NASA astronauts to the ISS by year's end, a goal both companies will mostly likely have to delay. Both have suffered setbacks. In April a SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule exploded. Boeing's Starliner experienced an engine failure in June 2018, causing delays for the aerospace giant.

“I don’t think it’s impossible but it’s getting increasingly difficult” for a SpaceX flight with astronauts this year," SpaceX vice president Hans Koenigsmann, told reporters on Monday.

Even the White House has weighed in, in a quest to get two astronauts -- a man and a woman -- on the moon by 2028. The Trump Administration has moved up that goal to 2024.

But as even billionaires and presidents have found out over the past 20 years, space is hard.

"Space is not an easy thing," Stallmer said. "It’s exciting, it attracts the imagination. It’s this frontier that we just long to be a part of."