Why Some Think 47 GOP Senators Broke the Law With Iran Letter

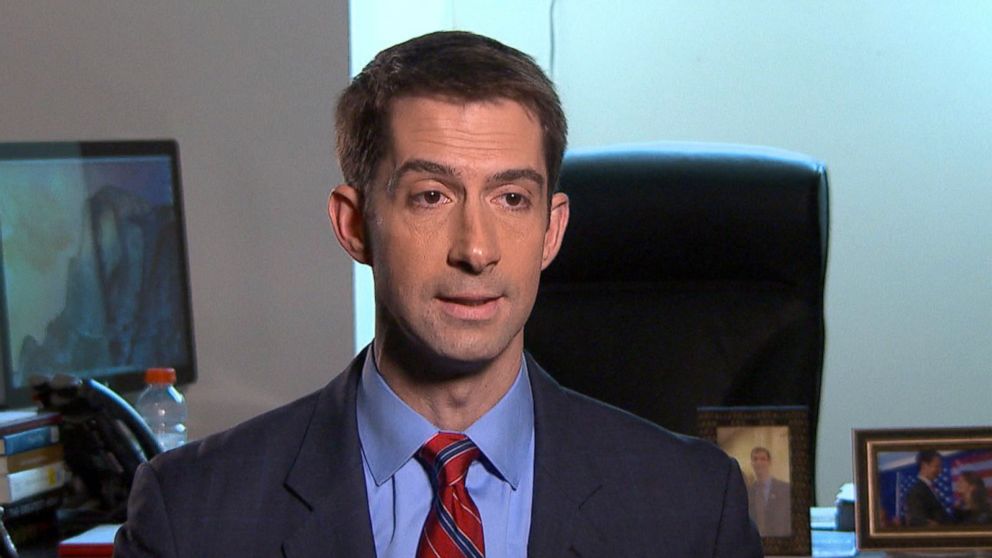

— -- Some law professors and liberal commentators say they believe the “open letter” Sen. Tom Cotton and 46 of his Republican colleagues sent this week to the leaders of Iran, warning them that any nuclear deal they sign with President Obama won’t last after Obama leaves office, might be a crime.

That letter from the Arkansas Republican to the ayatollahs and other Iranian officials, critics say, is a violation of the 1799 Logan Act, which says starkly:

“Any citizen of the United States, wherever he may be, who, without authority of the United States, directly or indirectly commences or carries on any correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof, with intent to influence the measures or conduct of any foreign government or of any officer or agent thereof, in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States, or to defeat the measures of the United States, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than three years, or both.”

“This [letter] seems squarely to satisfy the elements of the law,” Temple University law professor Peter Spiro declared, suggesting a crime has occurred here.

But hold on.

In the 215-plus years the Logan Act has been on the books, there’s only been one indictment against someone for breaking the law, in 1803, and the case fell apart before trial.

And what the GOP senators are doing here, while rare, is hardly unprecedented.

For instance, in 1920, 88 members of the House of Representatives sent a cable to British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and the British Parliament to protest against Britain’s treatment of Irish prisoners being held without arraignment or trial. This was directly contrary to the policy of President Woodrow Wilson, who sought closer relations with Great Britain at the time, and who did not support Ireland’s push for independence.

In 1927, the Senate’s anti-imperialist “peace progressives,” led by Sen. William Borah, R-Idaho), wrote directly to the Mexican president in an effort to renegotiate oil leases granted to U.S. oil companies under an agreement reached by President Coolidge.

In 1975, Sens. John Sparkman, D-Ala., and George McGovern, D-S.D., traveled to Cuba to negotiate directly with Fidel Castro about easing relations.

And the practice goes all the way back to the beginning of the country, when the House (dominated by fiery pro-French Jeffersonians) voted a resolution of approval of the radical French constitution of 1792, despite President George Washington’s desperate efforts to keep his fledgling country neutral in the great European wars that were unfolding.

The bottom line: As the great scholar Edward Corwin put it, “the Constitution … is an invitation to struggle for the privilege of directing American foreign policy.”

Cotton and his colleagues in Congress are waging that old struggle anew. Whether their “open letter” to the ayatollahs is wise is another matter.

(Cotton apparently fancies himself a constitutional scholar. In fact, he declares that the Iranian leadership “may not fully understand our constitutional system.” But his letter contains a pretty egregious constitutional error, one that would get him marked down sharply on a first-year con-law paper).

He writes that “the Senate must ratify [a treaty] by a two-thirds vote.”

But the Senate does not “ratify” anything. Ever. The Senate advises and consents to treaties and other international agreements, and the president, in the name of the United States, ratifies them as binding law on the country in its international relations.

This fact is not obscure. It is not hard to find. Indeed, a senator can find it on the Senate’s own webpage:

“The Senate does not ratify treaties. Instead, the Senate takes up a resolution of ratification, by which the Senate formally gives its advice and consent, empowering the president to proceed with ratification.”