How 2nd Trump impeachment could differ from 1st

President Donald Trump's unprecedented second impeachment less than a week before he leaves office puts the country in uncharted waters.

While some of the congressional processes around impeachment remain the same regardless of whether he is in power, the punishments and consequences are entirely different depending on his status.

Here's what to know:

The charges

The House voted to impeach Trump 232-197, on Jan. 13, a week after Trump rallied with a large group of supporters who ultimately rioted and sieged the Capitol. The incident left at least five dead and forced Congress to evacuate the chambers and take shelter in the middle of the hearing.

Hours later, after the all-clear was given, the Senate voted to ratify the election results, despite some Republican members still objecting.

The impeachment article contends that Trump "demonstrated that he will remain a threat to national security, democracy and the Constitution if allowed to remain in office and has acted in a manner grossly incompatible with self-governance and the rule of law," citing both his role in inciting the Capitol siege and attempting to subvert the election results.

This is different from the two articles the House approved against Trump in December 2019. In that case, Trump was charged with abuse of power and obstruction of Congress for allegedly attempting to coerce Ukrainian officials to provide election interference against then-Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden. Trump denied the charges.

The consequences

This marks the first time in history that a U.S. president has been impeached twice.

Although impeachment was used three times in the past to remove a sitting elected official, it can also be used against former federal officials, resulting in severe punishments that could affect their futures, according to the Constitution.

Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, in theory, gives Congress the authority to bar public officials, who took an oath of allegiance to the U.S. Constitution, from holding office if they "engaged in insurrection or rebellion" against the Constitution and therefore broke their oath. The article of impeachment filed by the Democrats cites this provision.

The president has indicated that he would run for office again in 2024, however, an impeachment and conviction vote by two-thirds of the Senate would open him up to a congressional ban on running for federal office. That punishment only requires a simple majority vote in the Senate.

There is a historical precedent for such a move.

During the Civil War, Congress voted to impeach and convict federal judge West H. Humphreys, who fled to the South and served as a Confederate judge. Following his conviction by the Senate in 1862, Humphreys, who was already out of office, was officially barred from holding office for life with a Senate vote.

The timing

While the consequences of Trump's second impeachment vote may be clear, the timing is still murky and may not be as swift as the three-week trial the last time around.

The House voted on the article before President-elect Biden assumes office, however, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell said in a statement released after the vote stating "there is simply no chance that a fair or serious trial could conclude before President-elect Biden is sworn in next week."

"Even if the Senate process were to begin this week and move promptly, no final verdict would be reached until after President Trump had left office," he said.

U.S. Rep. Jim Clyburn, the third-ranking House Democrat, told reporters the House might send the article of Impeachment to the Senate after Biden's first 100 days so that the president-elect and Congress can focus on the most pressing agenda. But Rep. Steny Hoyer, D-Md., the House majority leader, indicated that Democrats will try to move quickly.

New balance of power

The 2021 impeachment also comes under a political makeup for both houses of Congress.

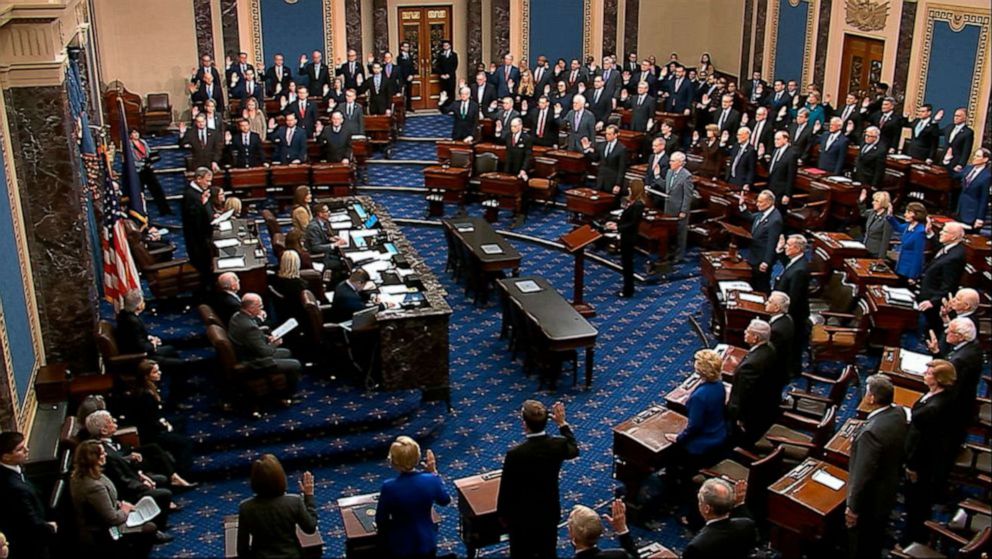

During the 2019 impeachment vote, all 195 House Republicans voted against impeachment, however, during the 2021 vote, 10 GOP members of the House, including Rep. Liz Cheney, of Wyoming, the third-highest Republican house member, joined Democrats in backing the second impeachment.

Trump was exonerated last year in the Republican-controlled Senate on both of his impeachment counts. Sen. Mitt Romney was the only Republican who voted guilty on the abuse of power count. The GOP voted along party lines for the second count.

This year, the Senate will be split 50-50 between the parties, with Vice President-elect Kamala Harris serving as the potential tiebreaker.

An impeachment conviction would require at least 17 Republicans to vote across the aisle to get the two-thirds majority needed.

As of Jan. 13, no Senate Republican has officially announced his or her support for impeachment, however, there were early rumblings that some party members think the president is culpable.

McConnell has told confidants that he believes Trump committed impeachable offenses, a source told ABC News. As the House voted on impeachment, he sent a note to Republican colleagues stating, "I have not made a final decision on how I will vote and I intend to listen to the legal arguments when they are presented to the Senate."

Romney said in a statement, "When the president incites an attack against Congress, there must be a meaningful consequence."

Sen. Pat Toomey, R-Pa., said he believes the president “committed impeachable offenses,” and his Senate GOP colleague from Nebraska, Ben Sasse, indicated he would be open to considering the House-passed article.

And Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, hasn’t yet taken a position on impeachment, however, she said she hoped the president would resign.

ABC News' Trish Turner and Allison Pecorin contributed to this report.