28 hours in Pyongyang: Reporter's notebook

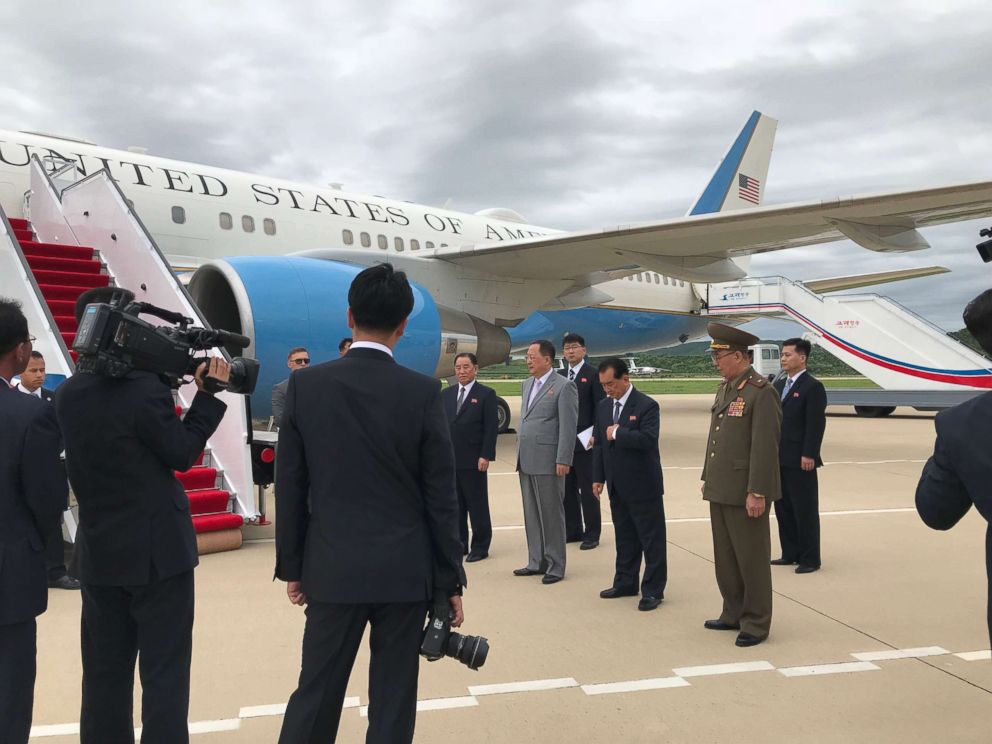

PYONGYANG, North Korea -- As we descended onto the tarmac at Pyongyang Sunan International Airport, locals emerged from the bushes to see the “United States of America” aircraft land.

We were in territory so forbidden, so foreign, even the scarecrows lining the runway seemed alien with their emoji-like smiley faces.

The airport had three terminals -- the word written in English -- but not a single aircraft at the Jetways. There were no signs of life inside either.

Vintage Air Koryo aircraft were parked on the edges of the airport like cars in an abandoned lot.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo traveled to the other side of the world for a one-on-one with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. It was the first opportunity to take the temperature on Kim’s commitment to denuclearize one month after he signed a vague agreement with President Trump to do so.

The newly minted secretary of state, under even more pressure to deliver after Trump declared North Korea is no longer a nuclear threat, arrived without knowledge of a schedule or even where he’d be sleeping that night.

Later, Nauert said that Pompeo knew all along what his accommodations would be even though it was not shared to other State Department officials on the trip.

In a statement, he downplayed the importance of deliverables like a timeline for denuclearization or an accounting of weapons and facilities, saying he was there to “fill in some details.”

Whisked away in a motorcade of Dodge Ram vans and ‘90s-era Mercedes, we traveled down a two-lane highway, with no traffic to block, to an elusive “guesthouse.”

“We don’t have many flights scheduled today, so there are not many cars on the road,” our minder, a desk officer in the foreign ministry, explained.

The locals on bikes, lined up at bus stops, or walking along the sidewalks appeared to be programmed not to look at the spectacle passing by.

A sign of a country grappling with famine, every piece of land appeared to be farmed, right up to the concrete on the highway and the airport tarmac. People fished in muddy streams.

What do the North Koreans expect from the talks?

“Like your president says, we’ll see,” the desk officer said with a laugh.

“In this van, no fake news?”

In the distance sits a 1,000-foot skyscraper in the shape of a pyramid: the Ryugyong Hotel. Construction started on the 105-story building in 1987 but, inside, it’s deserted because of a lack of financing.

The next behemoth site was the former presidential palace of Kim Il Sung-turned mausoleum for the first leader of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and his son Kim Jong Il. Their faces on the facade and their embalmed bodies rest inside a glass coffin, open for observation.

The road to our final destination -- the guesthouse known as 100 Flowers Garden where then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright stayed in 2000 -- was lined with weeping willows.

The grounds were picturesque, with gardens and a lake. The exterior resembled a 1980s timeshare with a concrete brutalist twist.

The interior was regal with red and gold-tone carpets and curtains, chandeliers, wall-sized murals and columns.

It was a gold-plated fishbowl where our conversations and clicks would be monitored. The U.S. State Department immediately set up satellite boxes for phone lines and Wi-Fi for its staff.

Seeming to crave affirmation for their hospitality, the North Koreans asked for updates on our comfort level. There was pride in their compound, which included a pool table on the third floor.

The rooms were equally regal, with gold-threaded comforters and tufted headboards, but the mattresses were as stiff as the floor.

The Ethernet cable was our only line to the outside world but it was plug in at your own risk. I brought a burner phone and laptop that would be turned off after liftoff and wiped upon my return.

We were physically in North Korea but, according to location services, digitally in Russia. Electronics seemed to be running slower than usual and Twitter was the only accessible social media.

Lunch was uncomfortably lavish, a four-course banquet with croissant, baguette, rice kwajul and sesame kwajul, kimchi, cold steamed chicken, rainbow trout marinated in coriander, roast salmon on iron plate, steamed hock with red sauce, parboiled oak mushroom and Korean cabbage, “Nutritious” boiled rice, fruits, chocolate cake, insam tea and ice cream.

The waiters were tall and beautiful, and walked at a synchronized pace.

While the accommodations were formal, the schedule was at the whims of the North Koreans, and conditional on how they saw talks progressing.

If all went well, Pompeo would meet with Kim Jong Un.

Pompeo, a former Army officer, seemed uncomfortable with the freewheeling. He waited awkwardly for North Korean Gen. Kim Yong Chol to arrive, an apparent power play by the former spy chief. The first remarks from Kim were about building trust.

The conference table where they would spend hours negotiating via translators was short two seats on the U.S. side.

After what State Department spokesperson Heather Nauert described as a night of “cracking jokes” and “exchanging pleasantries,” Pompeo, not trusting the telephone lines, left the guesthouse the next morning to make a call to President Trump.

When the meeting between Pompeo and Kim reconvened, there was palpable tension in the room. Even their pleasantries were chippy.

Kim suggested that Pompeo may not have slept well after their meetings, but he shot back that he slept just fine.

It was the start of a day of killing time before the main act that would never come.

The foreign ministry took us for a sanitized tour of Pyongyang. We made requests to stop at specific sites but were told, “It’s not on the list.”

On their agenda, a walk around the Mansu Hill Grand Monument, where hundreds of people lined up daily to bow before huge bronze statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. It was perfectly choreographed procession of people of all ages.

No one looked our way as we snapped away, as if they were expecting us.

The city skyline was architecturally eye-catching. There were also Soviet-style block apartments in bright colors like peach and turquoise. The layer closest to the road was the best kept, but complexes degraded further away from the main avenue.

Images of the “Dear Leaders” were on many buildings but none of the fountains in the squares were spouting water.

The town seemed staged for our arrival. The shelves in the shop windows were fully stocked. Not a single iconic anti-United States political poster was in sight.

“I don’t know what happened to them,” a desk officer, who would not give me his name, said. “We’re doing negotiations, the government is focused on that, so the posters reflect that.”

Are they no longer anti-American?

“The pain is so deep. It can’t be fixed in a day,” he said. “But we’ve been working on it.”

Women and men walked in clusters based on their civilian uniforms; younger women in white blouses and pencil skirts, middle-aged women under bedazzled umbrellas.

Back at the guesthouse, we waited for word on a meeting with Kim Jong Un.

With no schedule or status update, I dozed off. Then came a bang on the door.

“Hurry up, we’re leaving, quick, grab your stuff,” a fellow reporter yelled. Disoriented, I scrambled, still unsure if we were leaving for good or to see Kim Jong Un.

Instead, we were on our way to the airport.

Pompeo boarded the plane claiming that progress was made, and the North Koreans negotiated in “good faith.” But hours later when we landed in Tokyo, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) foreign ministry called the talks “deeply regrettable” and “gangster-like.”

Perhaps, to the North Koreans, a one-day historic summit complete with the promises of security and wealth can’t cure their deep suspicions.

Before the breakdown, Nauert, the State Department spokesperson, asked one of her counterparts from the DPRK in earnest, if the best way to contact him was through email.

“The New York channel,” he deadpanned, referring to North Korea's ambassador to the United Nations.