Could little-known 1921 'Tulsa Race Massacre' screenplay become big-budget Hollywood movie?

After being hidden away for nearly a century in the shadows of America's collective memory, the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 has sharpened into a powerful cultural focal point, with multiple film projects underway -- all vying for a June 2021 release to mark the centennial anniversary of one of the nation's worst incidents of racial violence.

Cineflix is producing a scripted miniseries called "Black Wall Street," directed by Dream Hampton of the "Surviving R. Kelly" documentary. NBA superstar Russell Westbrook has partnered with director Stanley Nelson for a documentary series, "Terror in Tulsa: The Rise and Fall of Black Wall Street."

Basketball great LeBron James and Maverick Carter's SpringHill Entertainment is working on a documentary directed by Salima Koroma. Singer John Legend -- who partnered with actress Tika Sumpter several years ago to develop a scripted series based on Tulsa's black community in 1921 -- is reportedly aiming to revive interest in his project after it was rejected by Hulu in 2016.

Now, a Texas professor whose movie project is nominally associated with imprisoned comedian Bill Cosby, his wife Camille Cosby and some of their Hollywood friends are publicly urging the other filmmakers to collaborate with his screenplay project.

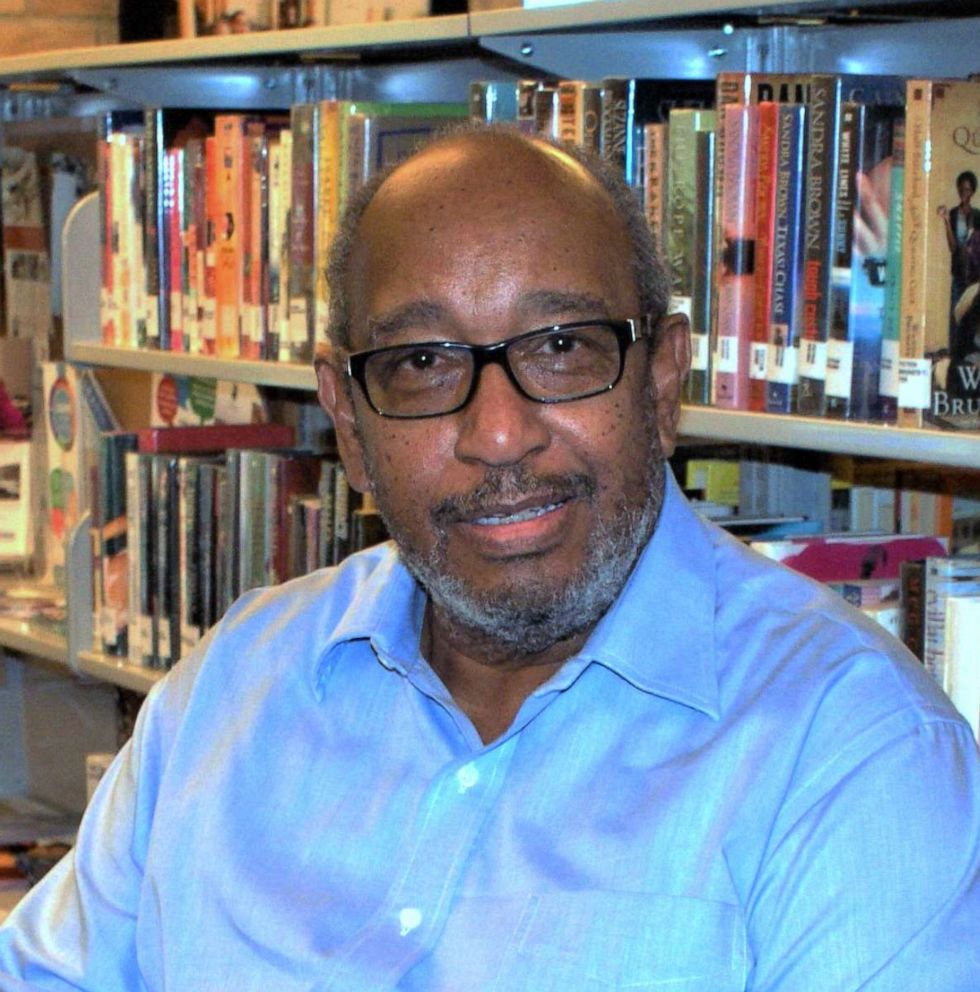

San Antonio College political science professor Frederick Williams, author of "Fires of Greenwood: A Novel Based on the Tulsa Riot of 1921," wants to produce a big-budget Hollywood film that immortalizes the key figures and the heroic efforts of many in Tulsa's Greenwood neighborhood to defend the community they'd built for decades against an overwhelming mob of armed white Oklahomans.

It's a proposal that has received a chilly reception given Cosby's controversial history surrounding sexual assault. While the Cosbys are not directly involved in Williams' project, it appears to have their tacit blessing.

Camille Cosby has granted the project sole access to a series of interviews that her National Visionary Leadership Project conducted with eight survivors of the 1921 attack, according to Williams. Her longtime friend, veteran film and TV producer Judith Rutherford James is involved in the Williams project, and the professor and Bill Cosby share a publicist: Purpose PR founder Andrew Wyatt.

Wyatt told ABC News that he has not yet garnered any interest in the project from any of the big Hollywood studios, or from any of the other projects already underway.

"First and foremost, Bill and Camille Cosby are not part of this project -- she's just lending her work," Wyatt said, acknowledging that his association with the couple as Bill Cosby's public relations crisis manager through two felony sexual assault trials could be impacting the response the project has received in Hollywood.

"Maybe this is part of that, but it should not be. ... Hollywood should look past that and take this project on to say 'This is the right thing to do," he said. "This is the right direction to take it in. I would like to think that I would be treated just like any major white public relations crisis management firm."

'Sensational reporting'

The attack -- which stretched across two bloody days on May 31 and June 1 of 1921 -- was sparked by a confrontation following the arrest of a young Black shoe shiner, Dick Rowland, who was accused of assaulting a white, female teenager named Sarah Page.

In 1905, oil was discovered in Tulsa, and within 15 years, it had become one of the most prosperous oil boom towns in the nation, home to hundreds of petroleum companies, numerous newspapers and a burgeoning community of Black Americans intent on finally being allowed to participate in the American Dream.

But for years, tensions had been building in Tulsa -- with "sensational reporting by The Tulsa Tribune, resentment over black economic success, and a racially hostile climate," according to the Tulsa Race Centennial Commission.

Rowland was taken into custody, and rumors spread through town that he would be lynched. A group of Black residents of Greenwood – some of them World War I veterans, according to historians – armed themselves and approached the courthouse to protect Rowland from the growing mob of white Oklahomans.

Among the Black war vets was O.B. Mann, who owned a grocery store in Greenwood before enlisting in the U.S. Army and fighting in World War I with an all-Black infantry division in Germany's Argonne Forest, according to Williams and other scholars.

Mann later retreated with fellow soldiers to take up strategic positions to defend Greenwood from an overwhelming mob of armed white residents who marched in and firebombed businesses and homes. Many Black residents were shot as they fled the burning buildings, according to historians and multiple newspaper accounts from the weeks and months that followed. Thousands of Black Greenwood residents were displaced, and as many as hundreds may have ultimately been killed, according to a 2001 Oklahoma state commission report.

Williams believes that, given the explosive growth of the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of George Floyd's death earlier this summer in Minnesota, the time is right for a positive, cinematic portrayal of the brave Black Americans who nurtured, built -- and later defended -- the sprawling Greenwood community back in 1921.

"Here's my major concern," Williams told ABC News in an interview last month. "Our kids need to see something good -- see some heroes for a change, you know? So now we're going to give them a massacre? What they're going to see is a massacre -- Black folks getting massacred again, Black folks getting killed. That does no good."

He went on, "When we wrote the script, we made sure that [when] Black kids and Black folks go see that movie, they're going to come out of this thing thinking 'Damn. Those were some good people that fought.'"

Another historic figure brought vividly to life in Williams' novel is J.B. (for "John the Baptist") Stradford, one of the founding fathers of "Black Wall Street" -- an entrepreneur who graduated from Indiana University with a law degree and moved to Tulsa, acquiring vacant land in the Greenwood neighborhood that he later sold to a wave of Black Americans fleeing the Jim Crow laws that kept them impoverished in the South.

Massacre at The Alamo?

Williams compared his vision for the film to old movies about the 1836 battle at The Alamo, in which Texas settlers and frontiersmen were overwhelmed and killed by Mexican forces during the Texas Revolution. Texas ultimately won independence later that spring after the Battle of San Jacinto, but settlers who died at the Alamo, like frontiersman Davy Crockett and Alamo co-commander James Bowie, were immortalized through film and fiction as brave American folk heroes.

"You don't ever hear them say 'Massacre at the Alamo.' What they do is they make Davy Crockett and Bowie heroes," Williams said. "So the heroes are the people fighting inside, even though they got wiped out too. So that white kids can come out of there feeling good. We need to do that for our Black kids, man. They need something. They need something. They're lost. And as an artist, that's been my goal for years from a writer's perspective."

These are battles in a far larger campaign for civil rights that Williams and other members of an aging Black generation of Hollywood producers and power players – with Bill and Camille Cosby at its center – have championed.

'Defending Black Wall Street'

The groundbreaking "Cosby Show" debuted on NBC in 1984. In the late 1980s, it was the most popular show on U.S. television for five years running. Beyond reimagining the flagging sitcom format, it was the first national TV show to feature a stable, well-educated, two-parent African American family, according to biographer Ronald L. Smith, author of "Cosby, The Life of a Comedy Legend."

Wyatt said Williams' project is aimed at recognizing some of the heroic architects of Tulsa's early 20th century "Black Wall Street" alongside the names of other key civil rights figures of the past century, like Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Dubois and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

"But you don't see J.B. Stradford or O.B. Mann, OK?" Wyatt said. "This is a new form of education.'"

Representatives for the other filmmakers did not respond to requests for comment from ABC News.