Syrian refugee graduates Columbia 12 years after beginning college

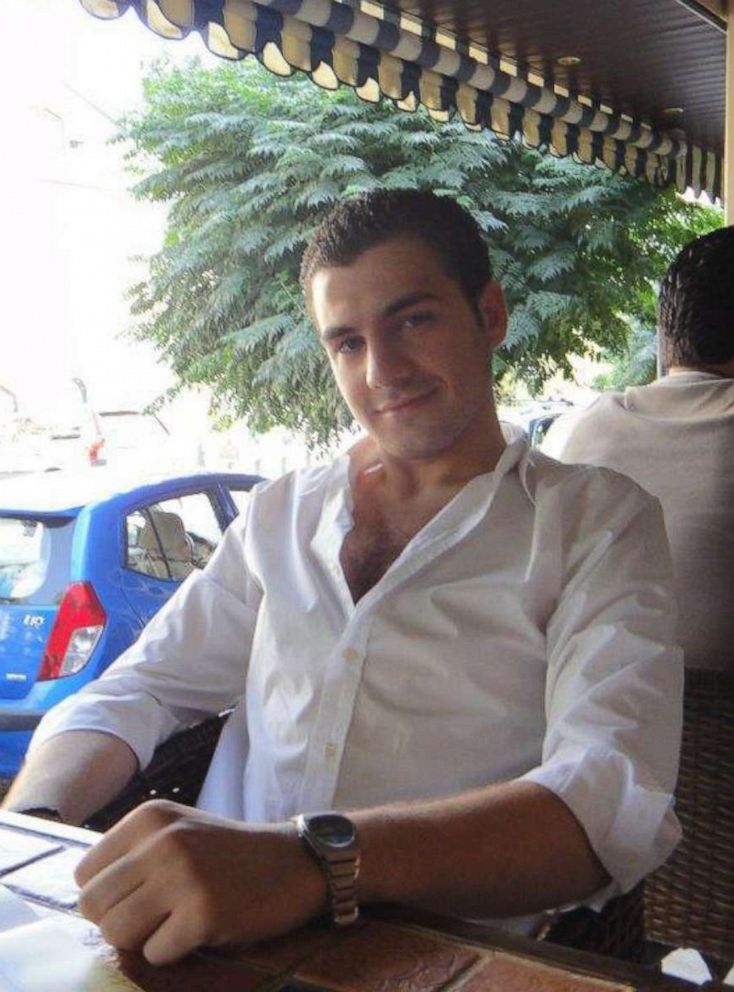

Broken, beaten, scarred and exiled. Qutaiba Idlbi is a survivor, and against all odds, he’s now an Ivy League graduate set on bringing freedom of expression to Syria.

For as long as he can remember, Idlbi, 30, has been fascinated by politics. The son of a local community leader focused on nonviolent political reform in Damascus, civil disobedience seemed to be ingrained in his DNA -- even if he didn’t know it.

“My dad was a torture survivor,” Idlbi explained. “He was afraid to tell me and my siblings about his mission because he didn't want us to be treated the same way by authorities.”

His father was detained eight times between 1965 and 1981 for pro-democratic activism. Details of the patriarch’s work were only revealed to Idlbi and his four siblings at their father’s funeral. He was just 15.

“People started going up to the podium and told us we deserved to know who he was,” Idlbi said. “It made me realize if I wanted to be this free-bird and speak my mind for the sake of reform, I had to be on my own or else my family would get hurt.”

Inspired to make his way in the world, the teenager moved out and put his education on the back burner, working upwards of 50 hours a week offloading supply trucks at a warehouse to pay the bills. He began researching online and went to local markets to distribute illegal pamphlets full of articles to those he trusted, profiling democratic struggles abroad.

“It's one of the most dangerous things you can do and people told me how dumb I was to do it, but they knew my family and what my dad represented so they eventually started taking it,” Idlbi said.

Tortured for speaking out

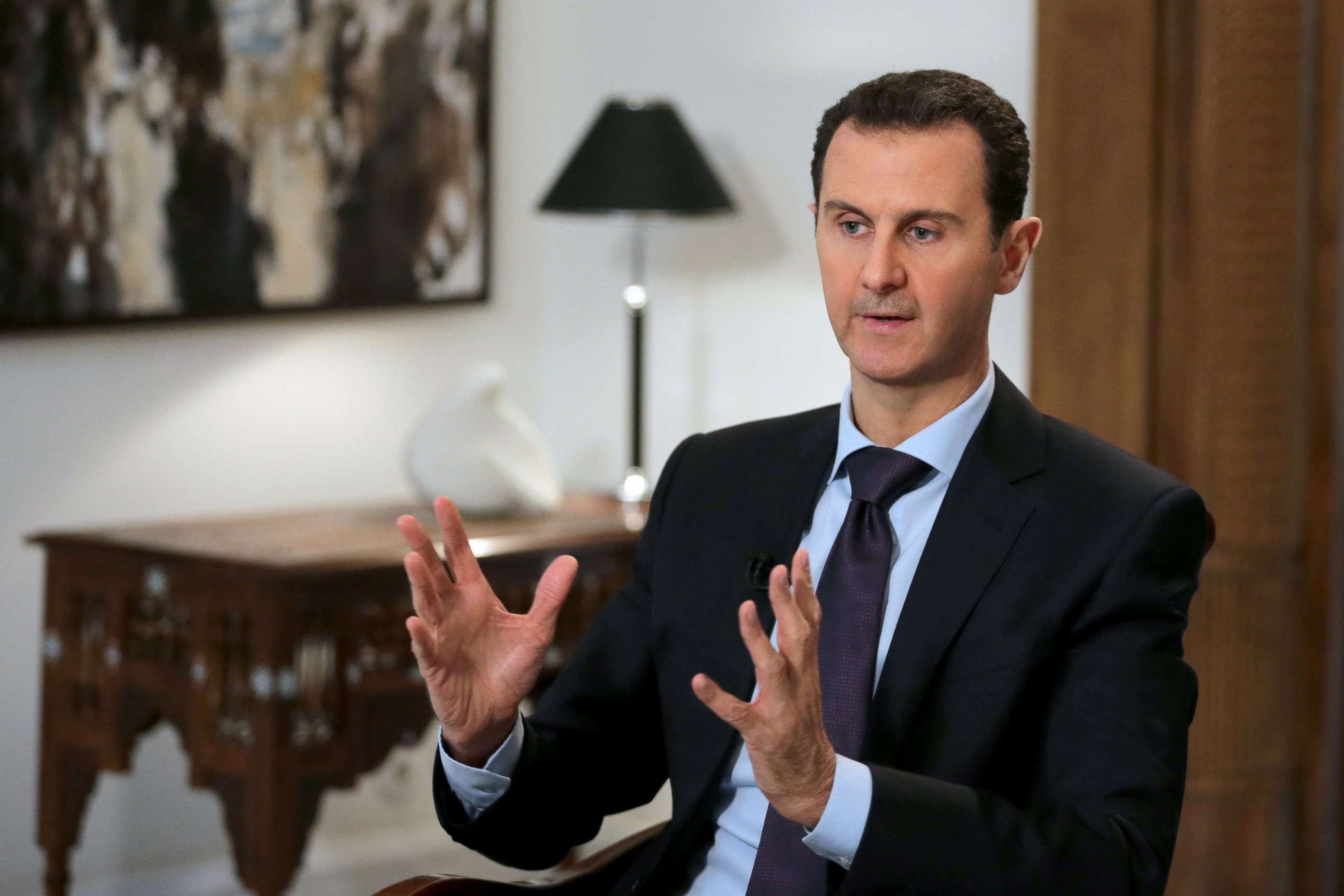

Determined to continue his father’s mission with an education, Idlbi finished high school three years later and entered Damascus University in 2008, still working full time to get by. As dissidence slowly grew across Syria, so did his acts of rebellion, secretly organizing pro-democracy demonstrations with tens of thousands of Syrians in 2011, which led to his arrest shortly thereafter. He says he was tortured by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s military forces while in custody, sometimes within an inch of his life.

“They call it a reception party when you arrive,” Idlbi said. “My clothes were taken and a doctor came in to examine my muscle mass. I realized after it was to determine the level of torture I could physically handle before my body would give out.”

According to Idlbi, a group of seven soldiers spent the next five hours slugging away wherever they pleased, beating him head to toe with various firearms and whips before rigging a generator to electrocute him. What followed was perhaps the soldiers most egregious assault -- the “flying carpet” -- a torture technique where victims are sandwiched face-up against their legs in between two slabs of wood as pressure is applied, almost guaranteeing a spinal fracture. It’s one of several methods former prisoners have described being subjected to in Syrian detention centers.

Through all the pain, Idlbi’s resolve never wavered.

“They wanted names of other pro-democratic sympathizers, but their torture had the reverse effect on me,” Idlbi said. “If I went through this, imagine if I told on someone and they had to endure the same thing. I wasn’t going to let that happen.”

Two days later, Idlbi was brought in front of Suheil al-Hassan, a brigadier general in the Syrian Air Force Intelligence service who has since been put on the U.S. sanctions list. After a short interrogation, Idlbi claims the high-ranking official threw him to the ground and began jumping on his head.

“My body wasn't even trying to protect itself at this point,” Idlbi said. “I felt like I was about to die, I don't remember when it stopped but was eventually taken back to my cell and released in a few days.”

Idlbi was formally charged with destruction of public property and said he left the prison a with a black eye, swollen face and broken body. He said he couldn’t wear his sneakers as he exited the facility because his feet were double their normal size due to inflammation.

Idlbi was detained once again the following week, just as he was about to take final exams for his last semester of college. This time he faced solitary confinement for 20 days in total darkness, a psychological torment he likened to “living in a grave.” The 21-year-old believes he was released only after an executive at the company he worked for asked a high ranking crony within the government to order his release.

On the run

Days later Idlbi fled the country with his youngest brother as authorities searched for him a third time, fearing he would likely pay the ultimate price if he was arrested once more as the brutality of the Assad regime only intensified.

Chemical weapons attacks, hospital bombings and the disappearance of over 100,000 prisoners are among the regime’s latest human rights abuses in a seemingly boundless list of atrocities determined to be “war crimes and crimes against humanity” by the Department of State.

U.S. intelligence assessments and United Nations investigators have repeatedly concluded the Syrian regime has dispersed chemical weapons on their own citizens with knowledge by the Russians. Syria and Russia continue to deny Assad’s forces have used chemical weapons.

In the first five years of the war, an estimated 400,000 Syrians were killed, according to the U.N. Envoy in Syria. As of April 2020, over 5 million Syrians have fled the country and more than 6.3 million remain displaced internally. Idlbi explained it’s statistics like these that motivated him to resume his education.

“I was always thinking, when would I be able to go back and finish,” Idlbi said. “I needed to get that degree to help my country find its way back. I wasn’t about to give up and turn my back on everyone.”

Laying low

After hiding for months in Lebanon, Idlbi eventually secured passage to Egypt in 2012 where his brother could resume a high school education. He began writing about refugees and went to political meetings where diplomats would discuss how to unite opposition factions in the now full-blown civil war raging in his homeland. It was at one of these meetings where he helped United States ambassador to Syria, Robert Ford, break up a fight between two diplomats. The pair instantly clicked and stayed in contact.

“Even though I was young, Ambassador Ford and his team valued my opinions on Syria,” Idlbi said. “I had a lot more knowledge at that point about all the struggles my dad went through in his days of activism. I was aware of the mistakes that happened and had realistic views on how things would be perceived on the ground.”

The ambassador eventually invited Idlbi to be a part of the Leadership Development Fellowship, an exchange program run by the State Department that gives Middle East stakeholders with grassroots organizational experience the “opportunity to complete training in civic engagement, social entrepreneurship and leadership.”

“Qutaiba is a symbol of a broader generation of Syrians that have so much to offer the world,” Ambassador Ford said in a statement to ABC News. “He’s quite articulate and we thought he'd be a great addition to the program.”

A fresh start

After completing the 12-week initiative stateside, Idlbi applied for asylum in 2013 and began working for a small foreign aid and development firm in Washington, D.C., focused on dispersing resources to Syrians based on input from people on the ground.

“The work was impactful but I knew I still had to complete my education if I was to fulfill my dream of building a better Syria,” Idlbi said.

But the Assad regime would come back to haunt the aspiring scholar once again. When Idlbi tried to access his academic records from his former university in Damascus, he was notified there was no longer any record of his education following orders from local authorities. He found little sympathy for his situation from American university admissions departments.

“No one would take me seriously because I didn’t have an official transcript to show them,” Idlbi said.

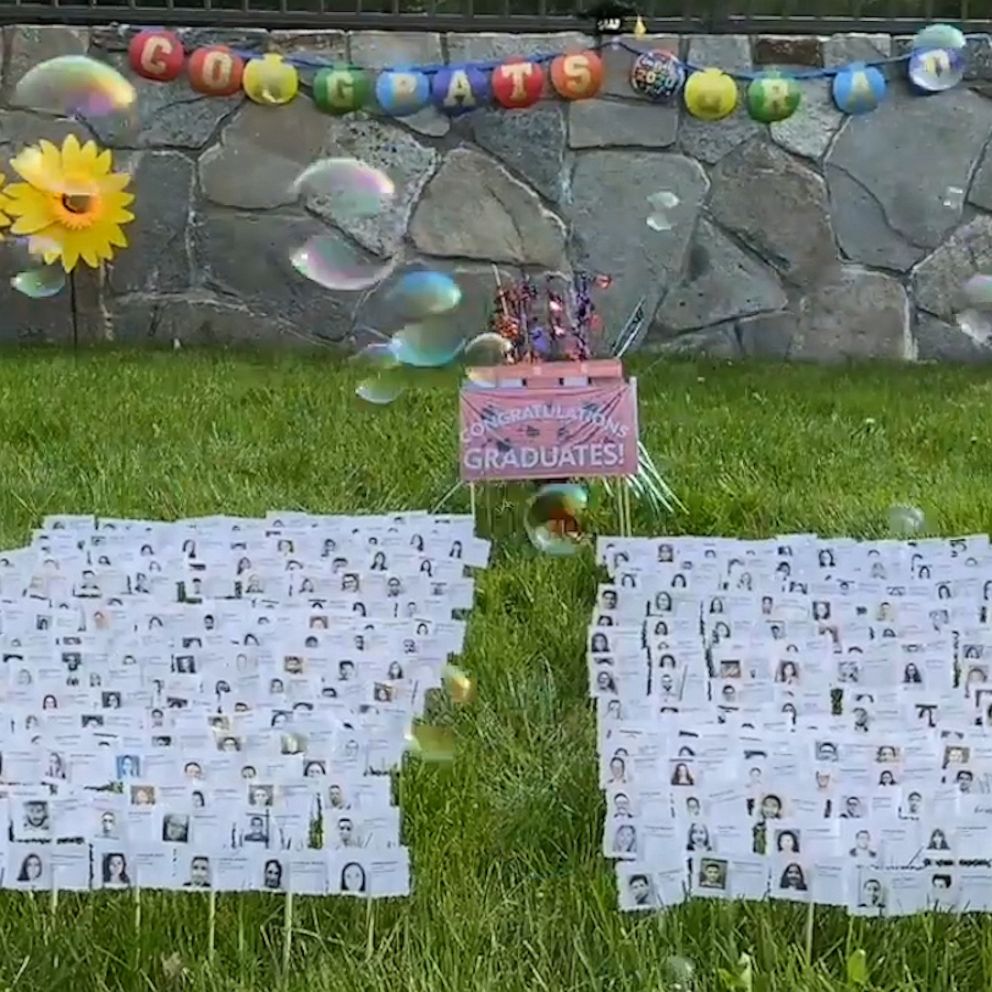

In an irony fit for the big screen, the door was about to be shut on Idlbi’s educational journey due to his meticulous work cultivating freedom of expression, a tenet claimed to be sacred by collegiate institutions across the country. That is until he heard about Columbia’s Scholarship for Displaced Students program, an initiative launched by the university in 2016 to combat the “unprecedented humanitarian and economic loss” for students displaced around the world unable to complete their higher education. Up to 30 applicants each year receive full tuition, housing and living assistance. Idlbi was accepted into the inaugural class.

“As soon as I arrived on campus, it felt like home,” Idlbi said. “It has truly been a life changing program.”

A degree that marks a milestone

Twelve years after first stepping on a college campus, Idlbi finally received his bachelor’s degree in political science on Wednesday. The Syrian refugee completed his studies a year early in an effort to free up a spot in the program for someone else who needs it. He worked full-time throughout his studies as a diplomatic contractor with the U.S. Army and resident fellow for the International Center For Transitional Justice.

“It has been an absolute pleasure to see Qutaiba flourish,” Jessica Sarles-Dinsick, associate dean for international programs and special projects at Columbia University, said. "His classwork reflects a deep commitment to the Syrian people as well. I am very fortunate to have had the chance to help support Qutaiba toward finishing his bachelor’s degree, and I could not possibly be more proud of him.”

Idlbi plans to take the next year to hit the books as he applies to law school and continues working on advocacy for Syrians. He hopes to return to Syria one day and open a small university where students can express themselves and their ideas without judgement or persecution -- a concept he knows would bring a smile to his dad’s face.

“I think my dad would have a lot of pride if he saw that happen,” Idlbi said. “I think it would mean the world to him.”

Idlbi's mother and four siblings remain political refugees in various Middle Eastern countries.